Syria’s nearly 14-year-long civil war has changed shape. Though there is still fighting and instability, the political transition means many who fled are beginning to return home. Yet for Sara Kontar, a Syrian photographer who has lived in France for nearly a decade, return remains impossible. European asylum law has transformed her exile into a cage: to visit Syria is to lose her residency and the life she’s made for herself. But to stay means giving up a part of who she is. Her story reveals a paradox of modern displacement, how safety itself becomes a trap, how being among “the lucky ones” can feel like abandonment, and how proximity to home, when legally unreachable, becomes its own form of suffering. Through her lens, Kontar materializes the unmappable geography of exile, where borders function not as crossings but as walls that seal rather than separate.

Sara’s story:

I became an exile in 2015 when I had to leave Syria. I’m originally from the South, but I was studying in Damascus at the time. By 2015, things had become really complicated. Bombs were falling every day. I love my homeland. But there was something I noticed—people didn’t see the future anymore. And that was much scarier. People were in survival mode. There was no more looking forward to anything. I just needed to build a better future, but I never expected to become an exile.

When I was a child, I didn’t have any notion of borders. Back then, we had family in Lebanon because my grandfather was born there before the Sykes-Picot agreement [the 1916 treaty that carved up the Ottoman empire between Britain and France], and as kids we travelled easily between the two countries. My Lebanese aunt and cousins visited us often, and we visited them. These borders existed, but to me they felt light, almost invisible, there was always this connection, and I never questioned it. After 2011, everything changed. My father was on his way to Lebanon for my cousin’s funeral when someone warned him to go into hiding because the Assad regime was after him. That moment marked the first time we felt the border as a wall, the first time we were cut off from part of our family.

The moment I left, in my head it was simple: I’m leaving for a few years, I’ll study, things will get better, and I’ll come back. I never imagined it would be this difficult. I didn’t have much knowledge about exile beforehand. In those first years in France, I was just adapting.

When I had to leave Syria in 2015, each border became an obstacle to cross, each one a huge ordeal—two months spent trying to cross them to reach my mother in France. The situations were often dangerous, sometimes requiring long walks. I developed this very physical connection to borders. We would wait in camps for days. You see the border, a gate that opens and closes controlled by others and they decide when you can pass. You just sit and wait, sometimes for hours, and then when it opens you go. This was the case between Greece and Macedonia.

But today—it’s going to be almost ten years now—I question this a lot. What is exile? Especially with the policies around it in Europe. Why do I have to prove my existence every day? I try to integrate in all the ways that are expected of me. I speak the language fluently, I completed my studies, I learned the culture, I work, I pay my taxes, everything that is supposed to make me a “good refugee,” a good example. I have done all of it.

But belonging is something else. It cannot take root in a society where I am constantly asked to justify myself, to tick every box, and still it is never enough.

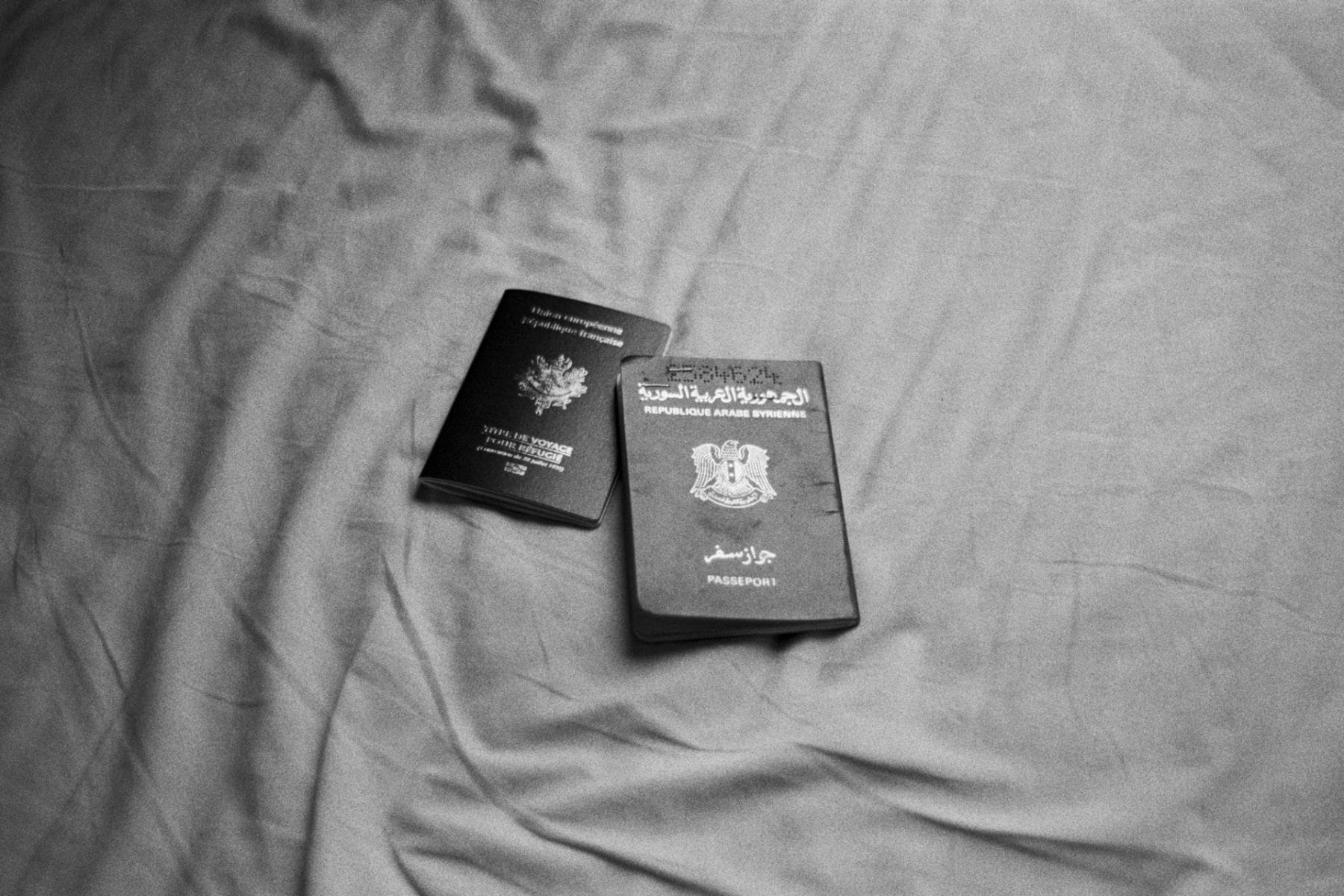

As a political refugee, I only have a travel document. I have no Syrian papers. And it clearly states that I cannot go to Syria. If I enter the country, I lose my residency. I would have to give up the life I’ve built here just to visit my family, to see my father, to be present when my grandfather died. I don’t have the option to go back and forth, to keep any real connection with home.

At first I tried to accept it—I told myself that living here means losing certain privileges. But going home is not a privilege. Seeing your family members for the last time is not a privilege—it’s simply life, the bare minimum. Laws that deny this are profoundly dehumanizing.

When I think about borders, for me it’s not only geopolitical—they are actual walls. I have no choice; it stands right there, impossible to cross. That’s the real meaning of a border: the physical, unyielding reality of it. It’s a block.

Photography is my way of giving form to things. Exile is not a physical space, it’s not tangible. I live in exile. But where is that? What is that? And yet it’s real. I don’t feel connected to any physical place. But photography allows me to materialize something. I create a space through these photos. I’m trying to visualize exile.

The day I left Syria, the night before, my phone broke and deleted all of my images. I left Syria with nothing—no photos of my life with my friends, no memories. I had lost everything. During the journey from Syria to France, I chose not to document anything because I didn’t want it to be part of my life. So I refused to record it.

A few years later, as I realized I was starting to forget, I began to panic. My fear wasn’t only about forgetting the events—it was about losing the feelings, the personal experiences that give them meaning. I thought about the importance of documenting and archiving—not just for myself, but for collective memory. If I forget, and no trace remains, what happens to our struggles, our narratives? What happens to the shared memories, to the archives?

I don’t know if art or photography can really make political change, but they help me connect with people who share similar experiences. Understanding these stories helps me process my own, it supports me mentally. Sometimes people here say, “You’re lucky—you have a story to express.” And I think, please, take my story and give me a normal life instead.

If I had a normal life, I wouldn’t hold onto these themes so tightly. I cling to them because they’re my reality—I don’t have another choice.

Of course, I think it’s important to work on these subjects, to talk about exile and displacement. But it’s equally important to remember that the real hope is that one day no one will have to live these stories in the first place.

I’m 29. I came here when I was 19. In February it will be 10 years. I was talking with a friend who visited from Syria recently. She lives in Damascus, she’s a filmmaker. I feel guilty when I talk to Syrians who are still inside. I feel like I left them or abandoned them. Because of that guilt, I’m always careful when I talk about my suffering in exile, since many people see living in Europe as a kind of privilege. But she was telling me that after traveling for just a week, she felt exhausted and thought, “I need to go home.” And I told her, if you want to understand my feelings, it’s exactly what you’re feeling now, but for 10 years. I never stopped feeling like I’m traveling. It never stops.