After a trip to the Winter Olympics in Italy, already marred by anger and protests at the presence of ICE agents at the games, JD Vance will embark on a victory lap of Armenia and Azerbaijan. It will be the first ever visit by a U.S. vice president to the Armenian capital Yerevan and the first to Baku since Dick Cheney’s brief 2008 whistlestop tour of the region. At war for decades, Armenia and Azerbaijan agreed to make peace in Washington, DC in August last year. The deal included the building of a “Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity” (TRIPP), a 21st century version of a Panama-style “canal zone” — a narrow strip of land that decides who moves energy, freight, and data between continents, and who gets paid for the privilege. And, vitally, a U.S.-backed counter to infrastructure being built by China.

TRIPP is more than a photo-op or a vanity project. The South Caucasus, particularly since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, has become an area of critical strategic value as a corridor between East and West and a new arena of superpower competition. “Vance is not well known for flying around the world just for fun,” said Svante Cornell, Research Director of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute in Stockholm. “The U.S. is serious about the TRIPP Corridor and they want everybody in the region to know that.”

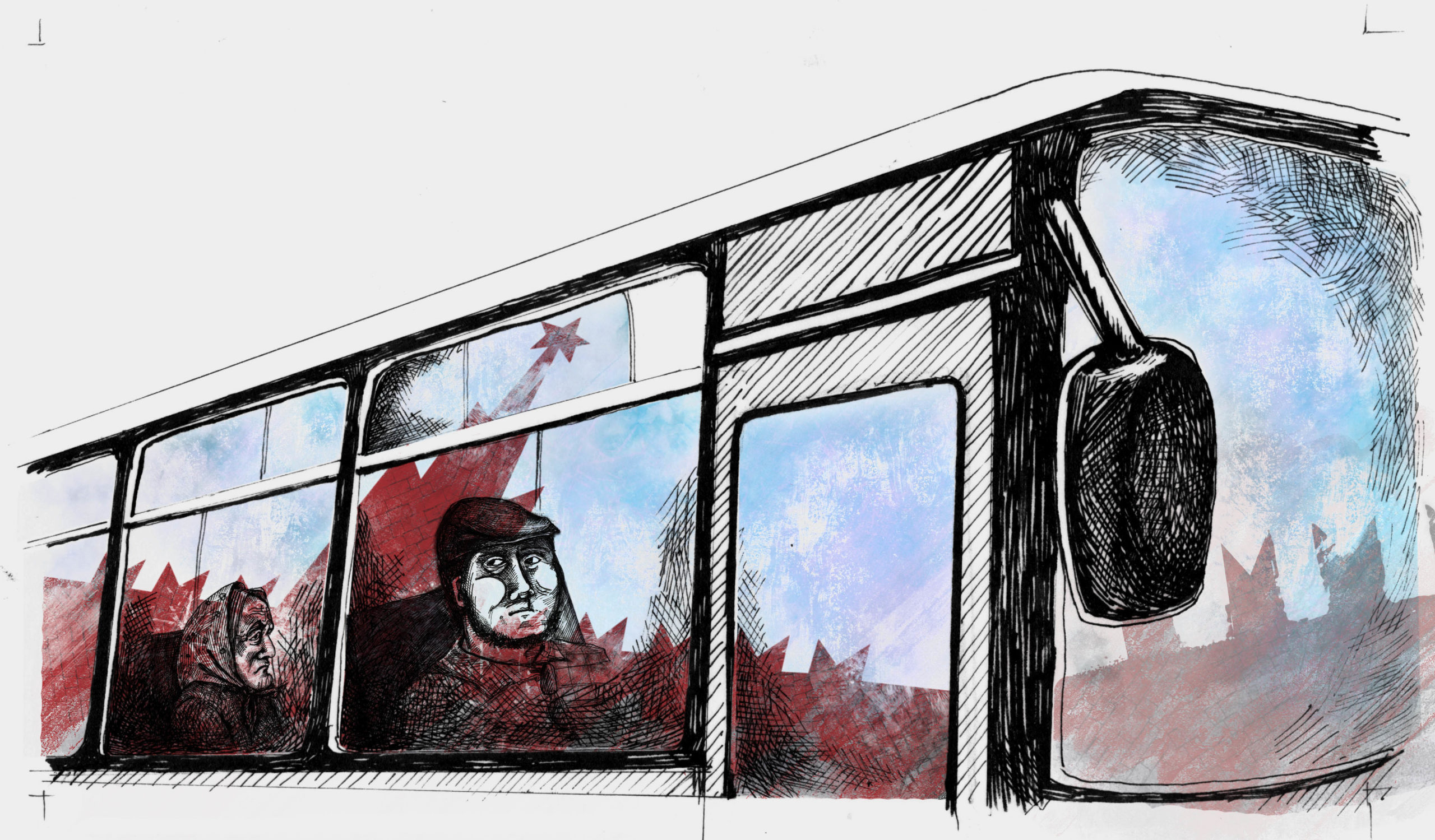

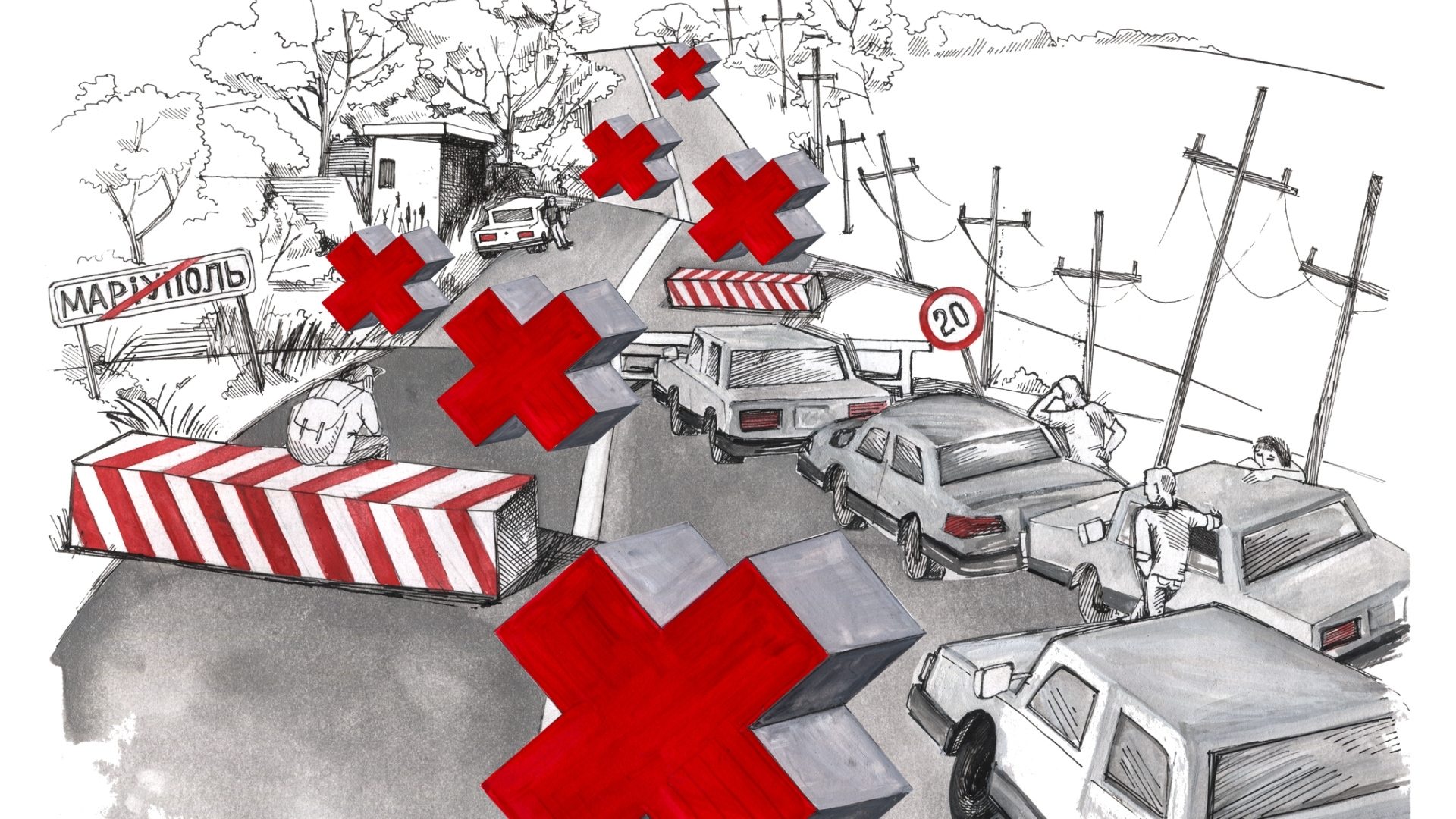

Armenia and Azerbaijan have fought two wars over disputed Nagorno-Karabakh since the late-1980s, as the Soviet Union collapsed. It has been a brutal, society-shaping conflict, followed in 2023 by Azerbaijan’s rapid takeover of Nagorno-Karabakh and the flight of nearly the entire ethnic Armenian population.

Russia, though formally cast as a mediator, spent years manipulating the conflict: arming both sides, managing ceasefires and preventing resolution in a familiar imperial tactic later perfected in Ukraine: manufacturing and freezing instability until it could be turned into full-scale war on Moscow’s terms. But Trump changed the narrative by brokering a peace that has continued to hold. In December, officials from both countries discussed “lasting peace” and a “joint future” at a summit in the Qatari capital Doha. Armenia and Azerbaijan are also deep in discussion about integrating their energy systems. And Washington is now trying to lock that peace into concrete: rails, roads, and fiber that physically re-route the region away from Russian and Iranian gatekeeping.

This, wrote Trump on Truth Social recently, “was a nasty War… but now we have peace and prosperity.” For once, the self-congratulation isn’t entirely empty. Trump – who has confused Armenia for Albania and talked about settling its war with “Aber-baijan” in Davos just weeks ago – can legitimately take credit for making geopolitical gains in what Russia considered its backyard.

The US president has repeatedly quoted Vladimir Putin as telling him: “‘I cannot believe you got this war settled’… cause it’s his territory.” That line matters because the South Caucasus is to Russia what the Caribbean Basin and the Panama “backyard” once was to the United States: a strategic near-abroad where outside powers aren’t supposed to build permanent leverage.

Hemispheric defense, the Trump administration has made clear when it comes to Latin America, is at the heart of its defense strategy and that it expects other superpowers to be similarly focused on their spheres of influence. Thus, Russia’s inability to be a reliable ally to Armenia will be seen as weakness to be preyed upon by rival powers. Armenia is now even talking to Turkey, a historical adversary, about opening their shared border and establishing diplomatic relations.

Still, Armenia remains a member of the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union and has its railway networks handled by Russia’s RZhD national rail operator — a factor Russia tried to use in an attempt to get involved with TRIPP. “Regarding the ‘Trump Road’ project, as it’s being called, we confirm our readiness to explore possible options for our involvement,” Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman, Maria Zakharova said in January. Armenia’s Parliament Speaker shot down the possibility as “absurd.”

As for Azerbaijan, Trump said on Truth Social that part of Vance’s visit to Baku would be dedicated to “the sale of Made in the U.S.A. Defense Equipment,” a prospect that won’t please Moscow.

Georgia, once considered Washington’s closest partner in the South Caucasus, is notably absent from JD Vance’s itinerary and being left behind is as consequential as being included.

For two decades, Georgia’s power and growing prosperity came from being the corridor: the place where pipelines, highways, and rail lines had to pass if Europe wanted Caspian energy without Russian control. The Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline was the signature project of that era, an “East–West energy corridor” literally running through Georgia. TRIPP threatens to redraw that map. A corridor through southern Armenia that becomes the new headline route doesn’t just “leave Georgia behind” — it means Georgia loses its most significant geopolitical bargaining chip because transit was the card it could play with Washington, Brussels, Ankara and Baku.

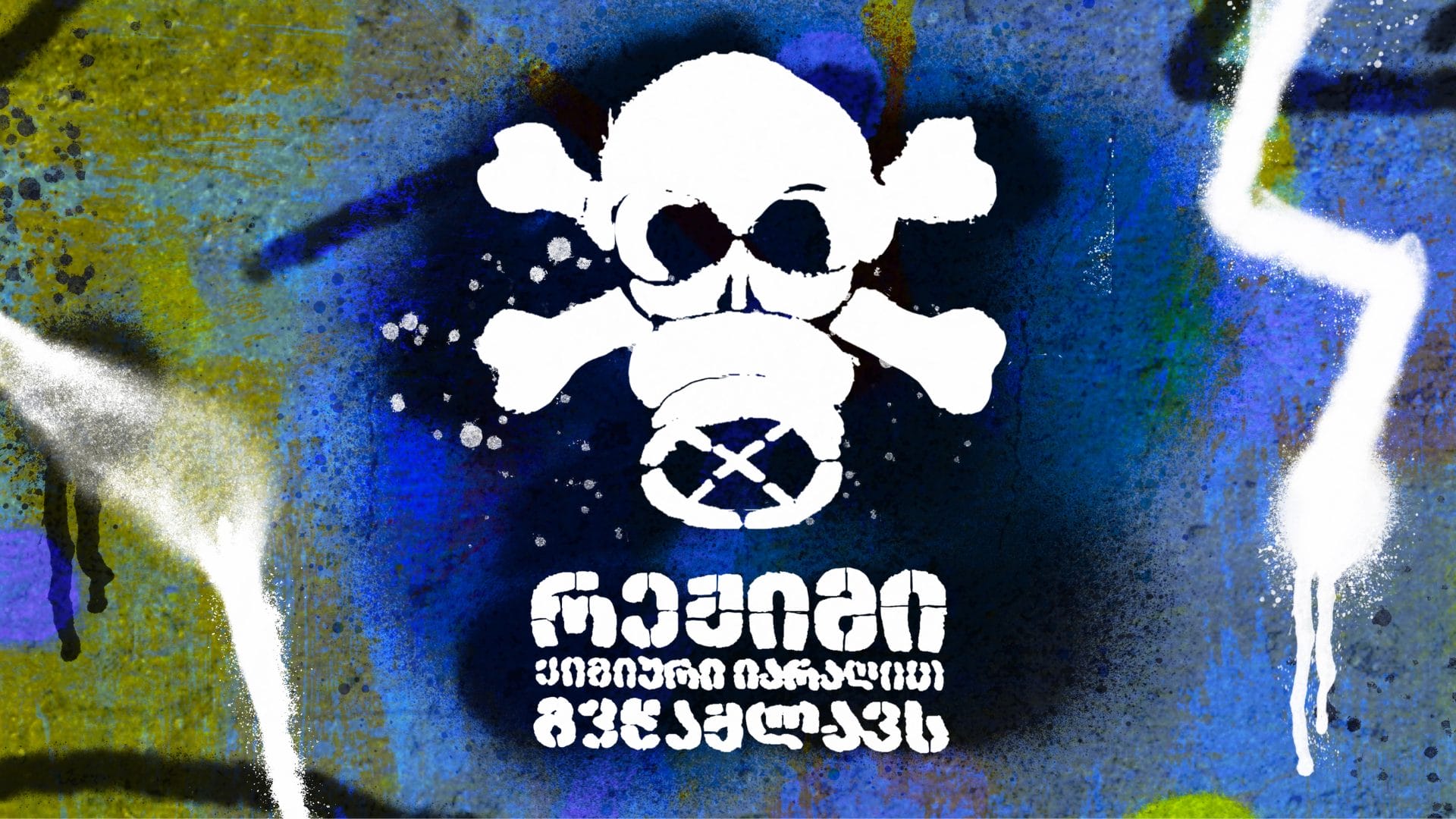

Now, as Washington invests in a new flagship corridor, countries like Georgia that fall outside it are forced to hedge. Over the past decade, Georgia has deepened ties with China through trade deals, cultural exchanges, and visa-free travel, while simultaneously sliding back toward Russia despite Moscow’s 2008 invasion of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Under the Georgian Dream government, repressive legislation and violent crackdowns on protest have widened the gap with the EU and the U.S. Georgian prime minister Irakli Kobakhidze has appealed directly to Trump for a reset, but TRIPP makes clear where Washington’s priorities now lie. With Azerbaijan and Armenia at the heart of a new U.S.-backed route, influence in the South Caucasus is reorganizing around infrastructure — and power is flowing along it.

TRIPP, even if it exists just on paper for now, indirectly challenges the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative, a network of railways, ports, pipelines, and trade corridors aimed at boosting international trade under Beijing’s leadership. It enables the moving of goods while bypassing Russia and, where possible, Iran — an approach that became more urgent after 2022. And it undermines China, which has been busy paving routes to Iran. Both countries have been in intense contact with Central Asian countries and last summer inaugurated a railway route that connects China and Iran through Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

The South Caucasus is just a small piece in a puzzle that fits together over 140 Belt and Road countries — and Cornell is skeptical about the scale of China’s ambition versus its actual investment. “Belt and Road maps include a lot of infrastructure in this part of the world that has nothing to do with China,” he told me. “Most everything that’s been built in the region has been built as a result of the funding from the countries in the region, not by Chinese funds.“ In keeping with this strategy, a fully operational TRIPP might be seen by China as a benefit, a way to trade while avoiding unreliable maritime routes. But researchers in China say that the problem will be if TRIPP “becomes securitized or if Washington leverages its control for geopolitical influence.” And with U.S. foreign policy increasingly waged as a battle with China for resources and global influence, TRIPP could become a threat to Chinese influence in the region.

Vice President Vance’s visit is a sign of sustained U.S. engagement in the region and a sign that Trump’s attention has not waned after a ceremonial peace agreement in Washington.

The simplest way to read TRIPP is as a 27-mile project with an outsized consequence: it reorders who controls the “land bridge” between Europe and Central Asia and it tells every capital nearby who Washington thinks matters.

And China will have to prepare for an economic standoff in terrain it once assumed was ripe for Chinese dominance. Russia, meanwhile, finds itself on slippery ground, no longer the indispensable broker it once was in its immediate neighborhood. TRIPP also adds an unexpected edge to the Ukraine-shaped narrative of a Trump administration willing to accommodate Moscow at every turn, suggesting instead a relationship that is less uniform and more selectively disruptive than it first appears.