“Our forests are not for sale,” said indigenous protestors in the Amazonian city of Belém, as they blocked the entrance to the COP30 conference on its opening day. Hosts Brazil have made a point of putting indigenous and underrepresented people at the heart of the global climate summit. They have told the world about the human costs of inaction and have called for climate justice. But a glaring exception has been made for China. At COP30, which ended on November 21, China received little criticism for its policies in Tibet and Xinjiang, for its resource extraction and its disregard for the rights of ethnic minorities.

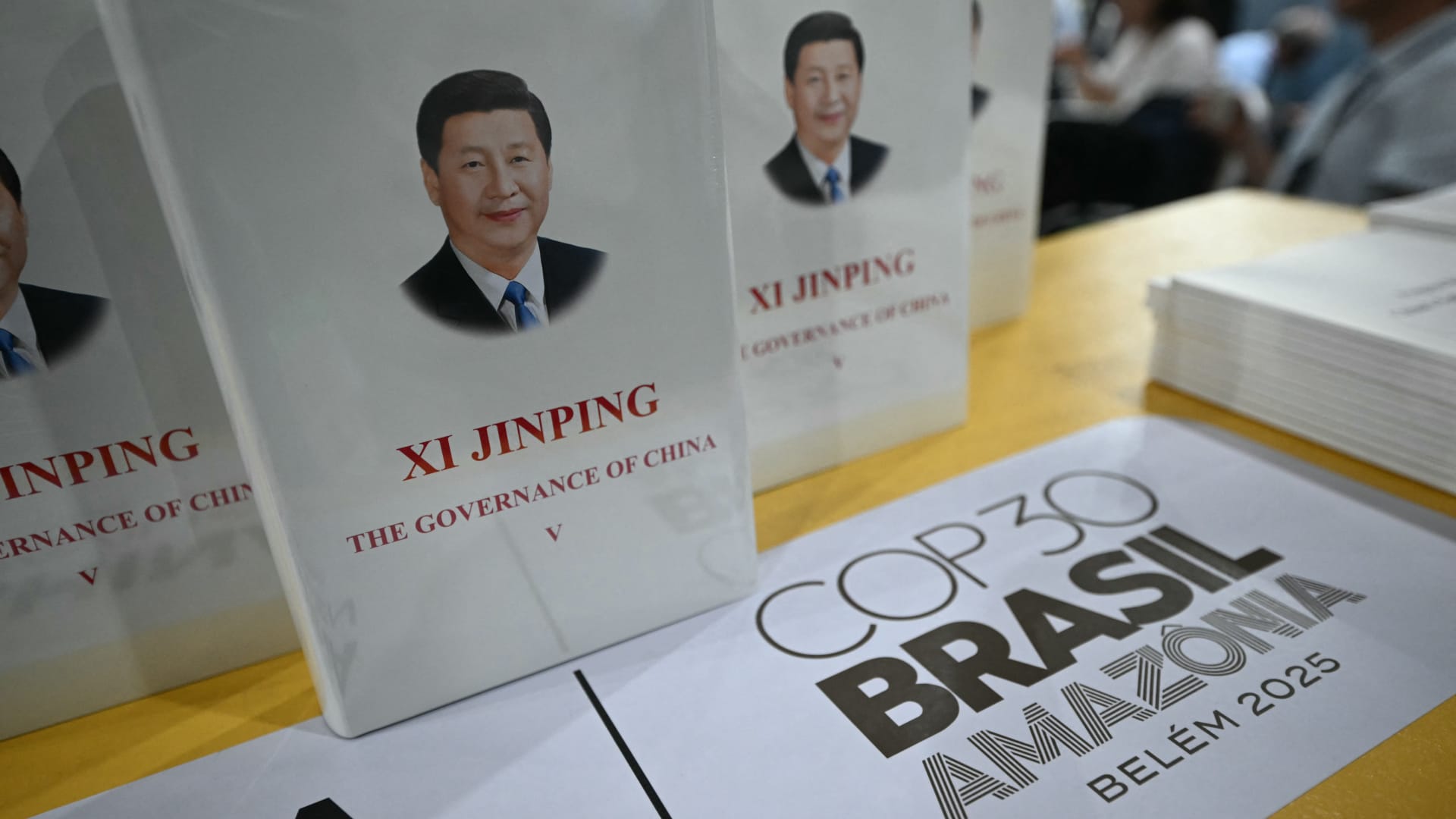

China has been the dominant force at COP30. It has made an effective case to be the global leader in the fight to avert the climate crisis in the absence of the United States, which not only did not attend the conference but is in the process of withdrawing altogether from the Paris Agreement of 2015, the international climate treaty. The U.S., which also withdrew from the agreement in Donald Trump’s first term, before rejoining when Joe Biden became president, now stands alongside Iran, Yemen and Libya as the only countries to not be party to the treaty. Country delegations and even climate activists have been loath to criticise China which dominates the climate agenda as the world’s largest emitter but also by far the largest producer of green energy, both in terms of generating it and building the technology to generate it.

The country’s enormous green energy industrial complex is largely located in Xinjiang (or East Turkestan, as advocates for Uyghur independence call it) and Tibet. Both are at the center of renewable energy expansion, lithium and mineral mining, and clean tech supply chains. In Xinjiang, the Chinese media celebrates the efficiency with which the government “transforms deserts into a renewable energy goldmine.” Renewable energies, particularly solar, are critical to Chinese, and presumably global, plans to produce the electricity demanded by AI computing and data centers. China controls over 80% of the solar panel industry supply chain, from raw materials through to finished products. But there is, say government departments in both the U.S. and U.K., credible evidence that modern slavery and forced labor play a large role in China’s dominant clean tech position.

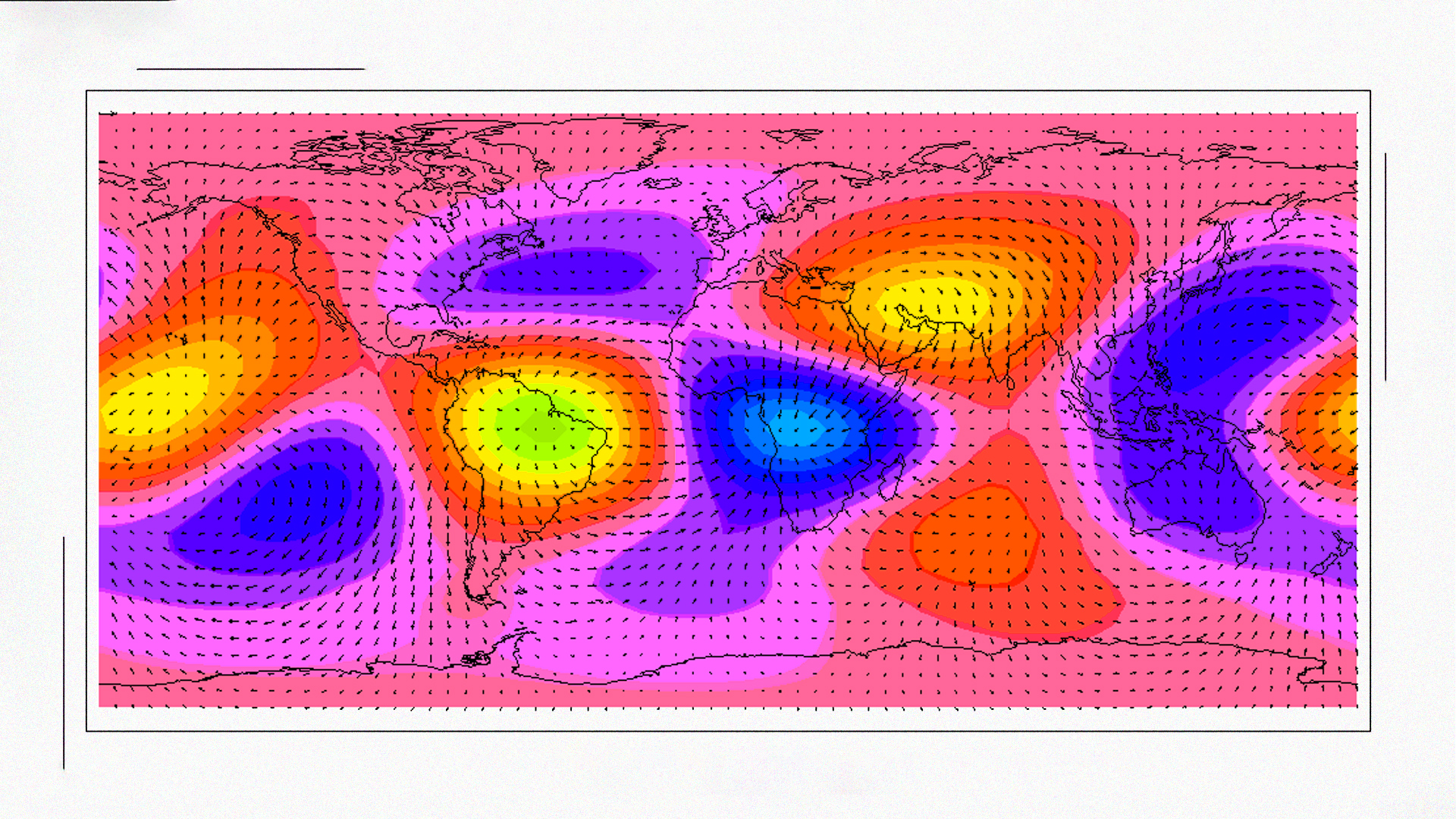

Tibet meanwhile is a major source for critical minerals, including the lithium that helps China dominate the production of batteries, electric vehicles and copper. China has also approved the construction of the world’s largest hydroelectric dam in Tibet, in a seismically active zone. The effect, claims the Stockholm-based Institute for Security & Development Policy, is that the Tibetan Plateau is “warming at more than twice the global average: glaciers are retreating, permafrost is thawing, grasslands are degrading, and the rhythms of water flow that support life across much of Asia are being disrupted.”

When approached, I’ve found that major global climate and environmental civil society organizations, nearly all based in the global north, are hesitant or unwilling to speak critically about China and completely silent when it comes to Uyghur and Tibetan human rights. Some Tibetan refugees, based outside of Tibet, have told me they’ve been excluded when trying to engage with climate justice organizations and networks. Last year, when over 1000 Tibetans were arrested after demonstrating against a planned hydropower dam in Dege, there was little international comment. And earlier this year, when the jail sentence of Tibetan environmental activist, A-Nya Sengdran was extended, there was yet more silence. You’d be hard-pressed to find even soft criticism of China from nearly all the major global climate or environmental groups. Perhaps it’s because global organizations like Greenpeace, World Resources Institute, WWF, and Conservation International, have offices or staff in China and speaking out on human rights could lead to Chinese staff being investigated or detained. But even groups with no China presence are largely quiet on rights issues.

At COP30, China basked in a diplomatic victory. André Corrêa do Lago, the Brazilian diplomat in charge of organizing the summit, said “China is coming up with solutions that are for everyone, not just China.” As countries push to agree to a “roadmap” at COP30 to phase out fossil fuels, they will have to turn to China for the technology to switch to renewable sources. This means everyone, including countries that might otherwise see China as a geopolitical rival. For instance, Britain’s Ministry of Defence has warned employees not to discuss sensitive information while they were using Chinese-made electric vehicles. The “MoD needs electric vehicles,” the Global Times were quick to point out, to “hit net zero targets” and so needs China. Britain’s anxiety then, the paper argued, is less about security and more about “China’s technological leadership.”

“China gets it,” said California governor Gavin Newsom, one of the few American political leaders to go to COP30. “America is toast competitively, if we don’t wake up to what the hell they’re doing in this space.” He wasn’t talking about the climate crisis. “It’s not about electric power,” Newsom said, “it’s about economic power.” As the U.S. turns its back on the climate crisis, it becomes inevitable that the world will continue to ignore the human rights and ecological abuses in Tibet and Xinjiang on which a Chinese-fueled global green transition is built.

A version of this story was published in this week’s Coda Currents newsletter. Sign up here.