When Felix Krauss was 15, he used to lie awake most nights and cry. He was terrified about the man-made environmental catastrophes that awaited the world in the future. Felix went on to begin a degree in environmental engineering. He joined protests against nuclear energy and participated in direct action against a coal mine. But eventually, he decided, small-time activism didn’t cut it. Better, he thought, to become the change he wanted to see in the world.

By 2013, he moved to eastern Germany to live in what he thought was an eco-commune project. The commune, though, was made up of a group of German ethnonationalist settlers determined to resurrect the German “Volksgut,” a reference to shared heritage and communal living off the land. The shared heritage was code for white and heterosexual and the plan was to buy up enough land so each family could cultivate and live self-sufficiently on their own plot. What might at first glance have appeared an idealized, bucolic homestead had unmistakable echoes of the Nazi concept of “blood and soil.”

The ethnonationalist identitarian movement, which emerged in Europe around 2012, propagates the Great Replacement conspiracy theory about the deliberate supplanting of white populations across the West with immigrants. Remigration, a core tenet of the movement, its answer to the so-called Great Replacement, has now become a political buzzword in both Europe and the United States. In October 2025, the Department of Homeland Security, either oblivious to or uncaring about the connotations, posted “remigration” and a link to its self-deporting app on X. And earlier in 2025, the Donald Trump administration proposed the setting up of an “Office of Remigration” as part of a revamped U.S. State Department.

Back in 2013, though, Felix was an early participant in what was still a nascent, if growing movement across Germany — the revival of an insular rural fantasy life as the answer to the disorienting, alienating, global megapolis. Already by 2015, identitarian activists were holding demonstrations in Berlin, unfurling a banner from the top of the Brandenburg Gate that called for “secure borders” as necessary for a secure future.

It was the year former German chancellor Angela Merkel would famously say “Wir schaffen das” (we can do this), adopting a compassionate, welcoming approach to migrants crossing into Germany. Between 2015 and 2016, an estimated one million refugees were allowed into Germany from Syria alone.

Ten years later, her party’s tone, as it seeks to deport many of those Syrian refugees, is markedly different.

Germany’s domestic intelligence agency, BfV classified the Identitarian Movement and groups associated with it as “extreme” in 2019. “These verbal firestarters,” said BfV president Thomas Haldenwang, who left office in 2024 and has yet to be replaced, “question people’s equality and dignity, they speak of foreign infiltration, boost their own identity to denigrate others and stoke hostile feelings towards perceived enemies.”

For years, far right extremists have been buying up land in rural parts of Germany, like the village of Wienrode in the Harz mountains. Here, they hoped to build their “traditional” off-grid communes and to recruit villagers for their cause. Felix was now a member, a part of the attempt to take over Wienrode. Their group, called “Weda Elysia” was led by Maik Schulz and, as they moved into Wienrode, they handed out flyers promising to “bring back the soul” of the rundown local bar that they’d bought. An undercover reporter recorded Schulz claiming that his intent in buying the bar and land in Wienrode was to turn it into a center “for German customs” and German families.” It was, Schulz allegedly said, “the last chance to save the race.” Wienrode, in effect, turned into a place of chosen exile where those dissatisfied with what Germany had become could create their own version of the ideal German nation.

Despite the BfV’s classification of Weda Elysia as right-wing extremists in 2024, the group continues to base itself in Wienrode. When I visited in 2025, some of the group’s remaining members had rented the house of Steffen Hupka, a notorious neo-Nazi who had moved to the area decades ago to turn a local castle into a training center for right wing parties. Hupka failed, but Weda Elysia has had more success. They’ve made inroads in local politics, with Schulz’s wife Aruna and another member winning seats on the local council (there was hardly any competition; they had previously bullied the town’s mayor into resigning.) Aruna even appeared on an Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) campaign poster in Wienrode.

AfD, which has also been classified as a right-wing extremist group by German intelligence, is currently the country’s main opposition party. The AfD’s newly formed youth wing is led by a 28-year-old who has long been associated with identitarian figures and who has rejected the official labelling of the movement as extremist.

Since its 1871 founding as a state, Germany has been a country of migration and seen several waves of widespread migration. At the same time, an ethnonationalist idea of citizenship was institutionalized by Germany’s 1913 citizenship law, which was drafted in a time where racism against Eastern European migrants was rampant. Here, unlike in other Western European countries like France and the UK, German citizenship was granted according to the “principle of descent by blood” and not by birth on German soil. This law was not reformed until 1999.

In the 1990s, fringe far-right parties got voted into some state parliaments, amidst post-reunification economic uncertainty and conservative chancellor Helmut Kohl’s anti-immigration policies. Today, polls show that the ethnonationalist AfD is on course to get 40% of the vote in Saxony-Anhalt’s state elections. There are several well-known neo-Nazis representing the AfD in local government in the Harz region.

Despite the attempt in 2019 to emphasize the threat represented by the identitarian movement, the rise of AfD has made those concerns politically mainstream. In some polls, AfD is now the most widely supported political party in the country. It has forced more moderate politicians to amp up their rhetoric. In October, Germany’s current chancellor, Friedrich Merz — who has been a longtime challenger of Merkel for the leadership of the center-right Christian Democratic Union — talked about “large scale deportations” of migrants and the “fear” Europeans feel in public spaces because of migrants who “do not abide by our rules.”

Of the Syrian refugees welcomed into the country by Merkel in 2015, Merz has said: “The civil war in Syria is over. There is no longer any reason for asylum in Germany, and, therefore, we can begin repatriations.” Merz’s language was vague enough to make it sound like he was effectively threatening forced deportations of tens of thousands of people, which would be a legal and logistical impossibility. But his words were not merely what pundits have described as a far right dog-whistle. Deportations between January and October 2025 were up 18% from the corresponding period in 2024 and up 45% from 2023. The German government is also trying to set up “voluntary” schemes that critics have described as a pressure tactic.

Of course, the return of ethnonationalist identitarianism, or at least identitarian talking points, is not just a German phenomenon. Identarianism, a label first coined in the 1960s in France, reemerged in France with the formation of the Bloc Identitaire in 2003. The youth wing, Génération Identitaire, was banned in France in 2021 for inciting hatred and violence. But as in Germany, in France too once fringe identitarian views are part of the political mainstream. With the French government narrowly surviving a recent no-confidence vote, polling suggests the far-right National Front candidate would easily win a presidential election, despite its leader Marine Le Pen being banned from standing.

In Britain too, Identitarian bugbears — particularly its anti-Islam and anti-migration stances — have been made mainstream by the likes of far-right activist Tommy Robinson. Incidentally, earlier this month Robinson said his legal bills as he fought off a terrorism charge in the British courts were paid by Elon Musk. More than an echo of European identitarianism can also be found in the recent emergence in the U.S. of a whites-only settlement in Arkansas called “Return to the Land.”

Back in July, 2020, the US-based non-profit Global Project Against Hate and Extremism released a report that white supremacist groups such as Generation Identity (GI) ran practically unchecked on social media, “despite their proliferation of propaganda such as the Great Replacement, which similarly inspires terrorism and argues that white people are being genocided in their home countries. ”The report found at least 67 Twitter accounts for GI chapters in 14 countries with over 140,000 followers.

In an example of once fringe identatrian conspiracy theories becoming mainstream, Donald Trump last year alleged that white South Africans were victims of “genocide,” and allowed Afrikaner farmers to claim asylum in the United States. And in September 2024, even before Trump began his second term, Stephen Miller, the current deputy chief of staff and homeland security adviser, posted that “remigration” was the “Trump plan to end the invasion of small town America.”

When I first spoke to Felix Krauss, he told me he’d left Weda Elysia in 2018 because of in-fighting. But, judging from his self-published memoir, he’d internalized the group’s extreme right views. His ideas, like those of many who were part of Schulz’s Weda Elysium group, can be traced not just to identitarianism or European ethnonationalism, but more directly to Anastasianism — a movement created by the fans of a 1990s fantasy book series.

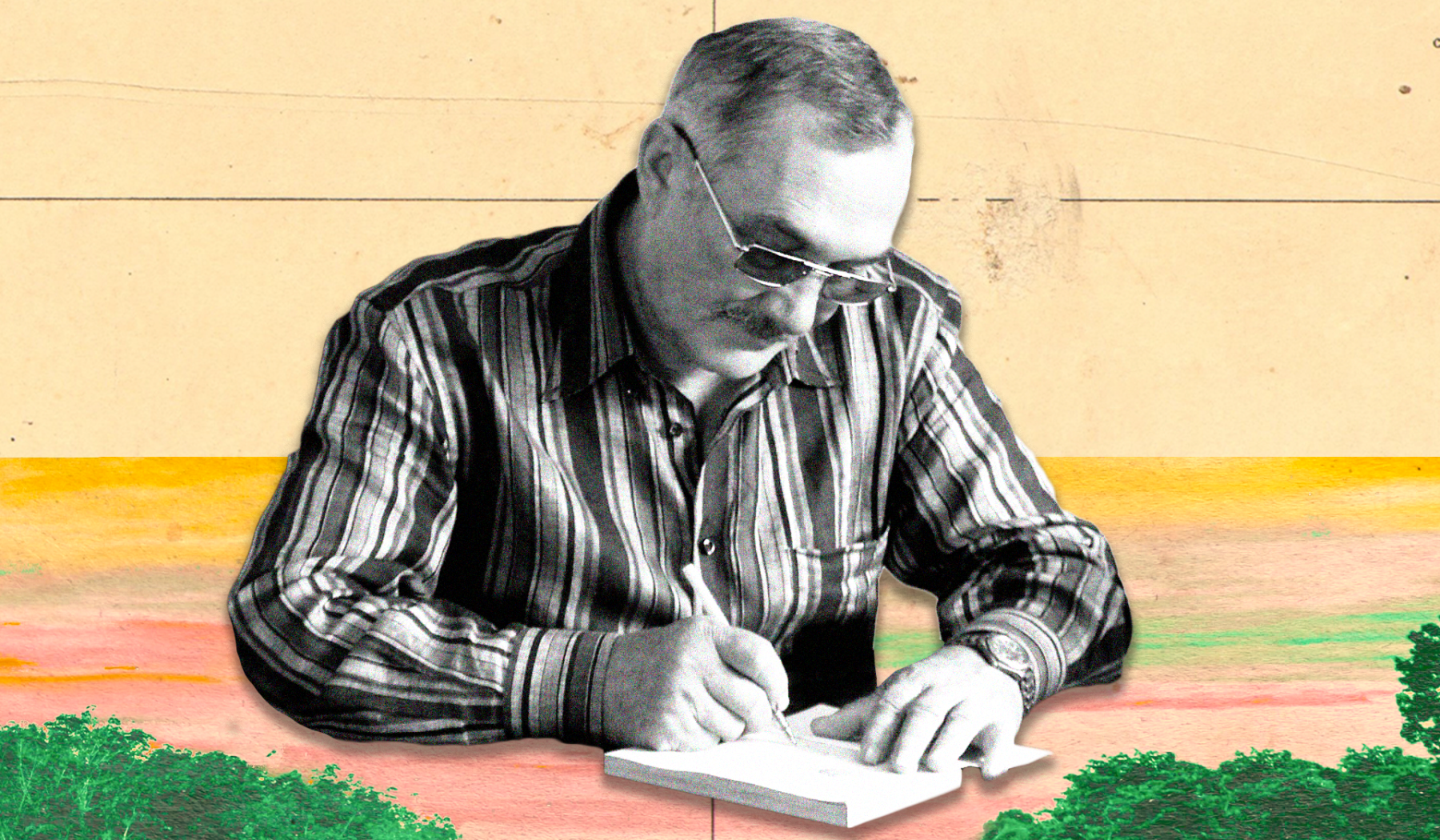

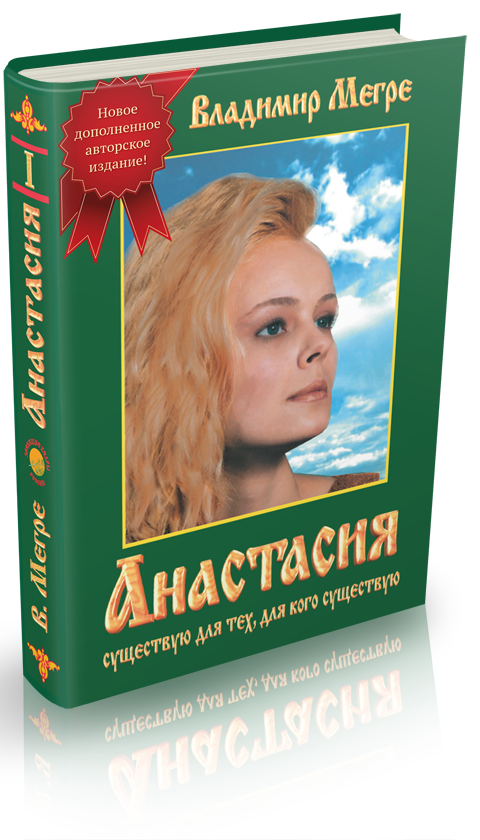

In the chaos of the post-Soviet ‘90s in Russia, a former riverboat tour guide called Vladimir Megre published a fantasy series called “The Ringing Cedars,” which he promoted as autobiographical, the product of an epiphany. He, a businessman, had been lost in a forest where he met a scantily-clad woman, the survivor of an ancient fictional culture put to sleep centuries ago by “the priests,” whom the series describes in grossly antisemitic terms. The woman bore his child and they lived on a magical self-sustaining farm. But he felt called to return to society to tell readers that they too could reclaim their lost connection to the natural world if they lived self-sufficiently on one hectare of land in a (heterosexual) family unit.

The first Ringing Cedars book was published in Russia in 1996. The books captured the zeitgeist. “Russian bookstores in the ‘90s were filled with illustrated fairy tales and myths about the history of Russia,” says Kaarina Aitamurto, a senior researcher at the University of Helsinki’s Aleksanteri Institute with expertise in contemporary paganism in Russia. After the collapse of the Soviet Union and a wave of devastating accounts about Soviet crimes, “alternative” history books were popular. Megre’s books sold 11 million copies worldwide. Since then, fans in various countries have tried to build the “ancestral estate” he described.

By September 2020, a Ringing Cedars settlement registration page in Russia claimed 389 settlements had been built, inhabited by about 6,000 people. Anthropologist Veronica Davidov, who came across a Ringing Cedars settlement in 2011, called the movement “reactionary eco-nationalist.” Disillusioned with the post-Soviet deregulated state, she wrote, Megre’s pseudohistory offered readers an alternative “heroic” narrative where they could live apart from the state and its services.

Megre, the author of the Ringing Cedars books, is now 75 years old. He runs an international online distribution service that sells bags of cedar nuts, cedar oil, and the Anastasian books, which have been translated into 20 languages. Environmentalist Nara Petrovic, who translated the Ringing Cedars books from Russian to Slovenian, told me she had run into Megre at several conferences for aspiring translators and publishers of the series. They met in Prague in 2002, Egypt in 2006, and Turkey in 2008.

“I’ve seen people from other cultures interpret [the books] to suit their own traditions,” he told me. In Slovenia, Petrovic said, he heard a theory that Megre’s fictional ancient civilization is based on the Vinča culture of southeast Europe which dates back to 5400 BCE. “I’m not 100% buying it,” Petrovic says, “because it’s so hard to go back that far and know how they lived, but as an idea it’s very emotional and touches people strongly.”

Anastasian settlements spread from Russia through much of eastern and central Europe. In Ukraine, the book series enjoyed a boom in the 2000s. At festivals, fans invented rituals to cosplay Megre’s fictional ancient civilization. Some tried to live as the books commanded, without electricity and growing their own food. People I spoke to said their priority was for straight couples to have babies in nature.

But then Russia invaded Ukraine, in 2014 and again in 2022. In one Anastasian village outside Kyiv, Kristina, whose parents’ settlement was caught in a crossfire between the invading Russian army and Ukrainian soldiers in 2022, told me that she and her neighbors do not talk about Megre’s books anymore. Some, she said, still cling to the idea of being part of a movement from Russia that will bring harmonious ecovillages to the entire planet. But “it’s an angry joke,” Kristina told me.

In other parts of Europe, the Ringing Cedars books’ romanticized back-to-the land narratives still have an enduring appeal. In Germany, by 2022, there were at least 17 such settlements, the biggest of which spanned over 200 acres. In Telegram groups, settlers (or wannabe settlers) posted conspiracy theories and videos about “Germanic culture”, including references to a myth, associated with the Roman historian Tacitus, and adopted by German ethnonationalists and Nazis that Germanic tribes were literally “born of the soil. And they also posted pictures of recipes and their gardens.

For a while, mostly before the media started covering Anastasianism’s German far right links, the books resonated at health and wellness events and in alternative agriculture circles. One German eco-villager told me that in the late 2010s, he would often meet people in his network looking for alternative communities and ways to connect with nature, who were convinced that the books offered solutions for “peace, for living away from materialism and an environmentally-friendly future” — People who wanted to opt out of the globalized, growth-dependent economic system sending us towards climate catastrophe. One of the people he spoke to was Felix Krauss.

In a 2021 essay for the Journal of Populism Studies, Heidi Hart wrote about the “tensions that emerge in neo-pagan media and practices, when they appeal not only to far-right enthusiasts but also to those with a left-leaning, environmentalist bent.” Ultimately, she concludes, “any group that follows a purity mentality, seeking deep, unadulterated roots in nature, risks nativist thinking.” I tried to get back in touch with Felix to discuss when his environmentalism shaded into nativism and how Anastasianism bridged the two. But he told me he didn’t want to speak to me anymore.

When Weda Elysia first moved into Wienrode around 2018, the village pastor told constituents not to go to their coffee and cake events, unless they wanted to wake up one day to police everywhere because “100 neo-Nazis next door are celebrating Hitler’s birthday.” Seven years later, on the surface it looked like little had changed. Hardly any villagers have officially joined Weda Elysia. And while the group may own the village inn, they don’t have self-sufficient homesteads and don’t farm their own food.

Still, the pastor and other critics of Weda Elysia are quieter now. Some anonymously, say they received threats, suffered damage to their property and were accused of “dividing” the local community. Weda Elysia may be the objects of state surveillance, but they are still in Wienrode as an entrenched part of the German far-right ecosystem, with AfD politicians and known neo-Nazis often spotted at their headquarters. At the 2025 edition of their annual winter market, I watched as straight-looking couples waltzed to the Nutcracker soundtrack and held candles aloft. One attendee openly described it to me as an “ethnonationalist Weihnachtsmarkt,” referring to a seasonal street market common across Germany in the month leading up to Christmas.

Ruth Fiedler, a representative of the Die Linke party (The Left) in the district, told me that the participation of Weda Elysia members in village and district councils was one example of how power dynamics in the region were shifting. “It is getting harder for people to distance themselves from right-wing extremism,” she said. “When it is their neighbors, people they work with.” In a recent town hall meeting, Aruna, the wife of Weda Elysia leader Maik Schulz, told Fiedler that it is the extremist right-wing group that “are the real democrats.”