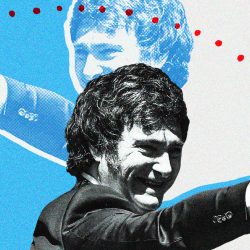

José Antonio Kast, the new Chilean president, will assume office on March 11, 2026. His comprehensive victory over Jeannette Jara, the candidate of the ruling left-wing coalition, was another swing of the pendulum in Latin America towards the right. And towards Donald Trump.

Argentina’s president Javier Milei greeted news of Kast’s victory with a map of South America, divided neatly into red (left wing) and blue (right wing) halves. Lined up on the blue side were Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador, with Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela prominent in red. “The left recedes,” posted Milei, “freedom advances.” Not surprisingly, president-elect Kast’s first trip after the election was to Buenos Aires this week where he embraced Milei and posed with a chainsaw, a reference to their shared promise to slash budgets and the size of their governments. Kast also found time in Buenos Aires to support Trump’s desire to force regime change in Venezuela. “It solves,” Kast said, “a gigantic problem for us.”

This year has been terrible for incumbent left wing governments in South and Central America. In Ecuador and Bolivia, right-wing candidates were recently elected to office. Last month, Hondurans voted between three candidates; left-wing candidate Rixi Moncada trailed a center-right and a Trump-backed far-right candidate locked in a virtual tie as the country sent soldiers into the streets to calm tensions. Next year, both Colombia and Brazil will head to the polls in highly-anticipated elections. Kast, who lost in two previous attempts to become president, is arguably the most right wing politician to be elected president in Chile since the end of Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship in 1990. Kast’s brother was a central banker during Pinochet’s rule and his father was a member of the Nazi party. “In a way,” Chilean academic Victor Muñoz Tamayo told me, “this is an election of our political moment.”

On Wednesday, Donald Trump posted that “Venezuela is completely surrounded” and will be “until such time as they return to the United States of America all of the Oil, Land, and other Assets that they previously stole from us.” Alongside oil, the U.S. government prizes access to critical minerals. In the vast desert region known as Norte Grande lies an expanse of salt flats on the borderlands between Chile, Bolivia and Argentina. It is known as the “lithium triangle.” Here, roughly one-third of the world’s supply of lithium sits beneath the surface of the earth. Extracting this rare element, a key component of electric vehicle batteries, requires large quantities of water: roughly 500,000 gallons per ton of lithium carbonate. While the incumbent Chilean government sought to regulate the extraction of lithium and nationalize its production, Kast has said he favors a market approach. “They don’t believe in climate change. They don’t believe in protecting the rights of nature. They don’t recognize ancestral communities,” says Daniela Rodriguez, a local “journalist and activist” in the town of San Pedro de Atacama.

The choice of location – the upscale Santiago neighborhood of Las Condes – for Kast’s victory speech was no accident. In front of a crowd of thousands in this area of sleek high rises and banks nestled just below the nearby mountains, Kast said “Chile won. And the hope of living without fear won.”

In the first round of voting in November, Jeannette Jara, who ran on a coalition platform that spanned from Communists to Christian Democrats, came out on top – garnering around 27 percent of votes. She beat out Kast, populist Franco Parisi, far-right libertarian Johannes Kaiser and center-right Evelyn Matthei. Originally from Conchalí, a poor commuter suburb of Santiago, Jara highlighted her working-class roots and accomplishments as labor minister under president Gabriel Boric. In this role, Jara passed laws to raise the minimum wage, gradually reduce the work week and partially reform the country’s private pension system – a legacy of the 17-year Pinochet dictatorship. In Chile, Boric was elected on a wave of popular discontent that coalesced in the nationwide 2019 social movement known as the estallido social (social outburst), but once in office, he struggled to impose his transformative vision, including a rewrite of the 1980 constitution. Jara’s party affiliation and her connection to Boric (whose approval rating sits around 30 percent) hampered her candidacy.

In campaign spots, Kast frequently red-baited Jara, playing on long-held fears of the Communist party that still persist in Chile. “Vote 5 [Kast’s ballot number], without communism, without communism,” went the lyrics of one popular campaign jingle. Kast has also minimized his previous support for Pinochet, whose regime arrested, tortured and disappeared thousands of opposition members and leftists. As a candidate in 2017, Kast said he would have voted for the dictator and has said Pinochet “saved” the country from communism. Though he was once known for his extreme policy positions, Kast successfully moderated his tone when campaigning. “In the past,” Muñoz Tamayo explained, “he talked about things like eliminating the Ministry of Women. Now, he focuses on public order, crime, and uncontrolled migration. They’re right-wing, radical issues, but also very popular.” There are an estimated 336,000 undocumented refugees in Chile, many of them from Venezuela.

It’s an issue that has made some voters ignore Kast’s praise for Pinochet. I traveled to Los Vilos, a couple of hours north of Santiago by bus, where I met former student activist Joaquín Vidal at the seaside bed-and-breakfast he runs. Vidal showed me tokens he kept in a box from his eight-month spell in prison for participating in a protest against Pinochet’s rule. He went into exile in 1982. One of the items he’d kept in the box was a leather belt signed by his fellow inmates. “Normally, I’d give these items to the Museum of Memory and Human Rights,” he told me. “But I’m worried the far-right might shut it down.”

In parliamentary elections on November 15, right-wing parties gained a majority in the Chamber of Deputies, giving Kast an unprecedented mandate. While campaigning, Kast was able to reassure a country paralyzed by fear that he was focused on the issues that mattered to them. But executing on his promises, which include forcibly removing hundreds of thousands of undocumented immigrants and implementing austerity measures will be difficult. Over seafood in a Santiago restaurant, Jorge Heine, Chile’s former ambassador to China, South Africa and India, told me that Kast “does not have a proper team of experienced public policy specialists and professionals to run the country.” This, he added, “does not bode well.”

Despite the tenor of the election, Heine told me, “the truth is Kast will be handed a country that is in pretty good shape and by no means ‘in crisis,’ as he likes to say.” The question is, “will he act like [Italian prime minister Giorgia] Meloni or Trump?” Chile’s election of a Trump-supporting right wing president comes at a time that the White House has revealed its extensive plans for the region.

“American sweat, ingenuity and toil created the oil industry in Venezuela,” posted Stephen Miller, the White House deputy chief of staff. “Its tyrannical expropriation was the largest recorded theft of American wealth and property.” It’s an attitude that informs current White House policy in Latin America, even though the United Nations enshrined the principle of “permanent sovereignty over natural wealth and resources” in 1962. Miller is effectively saying that countries like Venezuela should not be sovereign, but instead vassal-states. The ‘Trump Corollary,’ the U.S. government’s updating of the 19th century Monroe Doctrine, claims “as a condition of our security and prosperity” the right to “assert ourselves confidently where and when we need to in the region.” Its actions in Venezuela are a demonstration of this intent.

By deliberate contrast, in a recent white paper on China’s Latin American policy, Beijing spoke of “setting a shining example of South-South cooperation” and of a “community with a shared future… founded upon equality, powered by mutual benefit and win-win.” With China having established itself as the region’s largest trading partner, Trump-friendly governments throughout the Americas, alongside the U.S.’s naval buildup in the Caribbean, will be necessary to counter Chinese influence in what the U.S. considers to be its hemisphere.

A version of this story was published in this week’s Coda Currents newsletter.Sign up here.