Indian prime minister Narendra Modi was at the airport on Thursday. In a move heavily trailed by the Indian media (thus defeating the purpose somewhat), Modi intended to surprise his good friend, the Russian president Vladimir Putin. Back in September, at a summit in China, Modi had been photographed with Putin as they rode chummily together towards the venue, where they would meet and share an equally chummy rapport with Chinese leader Xi Jinping. At the time, the overt friendliness was read as a rebuke of U.S. president Donald Trump, who had announced a 25% penalty tariff on Indian exports as a punishment for India buying Russian oil in unprecedented quantities, thus helping to finance the continued war in Ukraine.

Similarly, Putin’s two-day visit—his 10th trip to India but his first since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine—is less about a bilateral relationship than it is a message to the world. Russia retains support, Putin is saying, even as it is being accused of stalling and derailing any meaningful peace negotiations. Just before Putin arrived in Delhi, the Times of India published an op-ed by the ambassadors to India of France, Germany and the U.K. that accused Putin of having a “total disregard for human life.” It embarrassed India’s Ministry of External Affairs which said the article was “unacceptable and unusual” and accused the ambassadors of trying to interfere in India’s sovereign right to conduct foreign policy as it sees fit.

For Modi too, Putin’s visit is an opportunity to send a message to the U.S. that India will not be bullied by tariffs, even as the value of its trade with Washington dwarfs that of its trade with Moscow. Keeping Russia close is also vital to India to balance out Russia’s growing reliance on China. India shares a long, volatile border with China, and the growing power disparity between the two countries means Delhi needs all the support (from Moscow and Washington) that it can get.

Despite their need for mutual support, India and Russia’s relationship is not without its tensions. At a demonstration in Delhi, ahead of Putin’s visit, the families of Indians stranded in Russia held up placards that read “Our Sons Are Not Soldiers of Russia.” At least 12 Indians have died while fighting in the war and 127 have joined the Russian army. And India remains, despite Modi’s authoritarian tendencies, a democracy, with an influential civil society and a public that believes in its right to change governments at the ballot box.

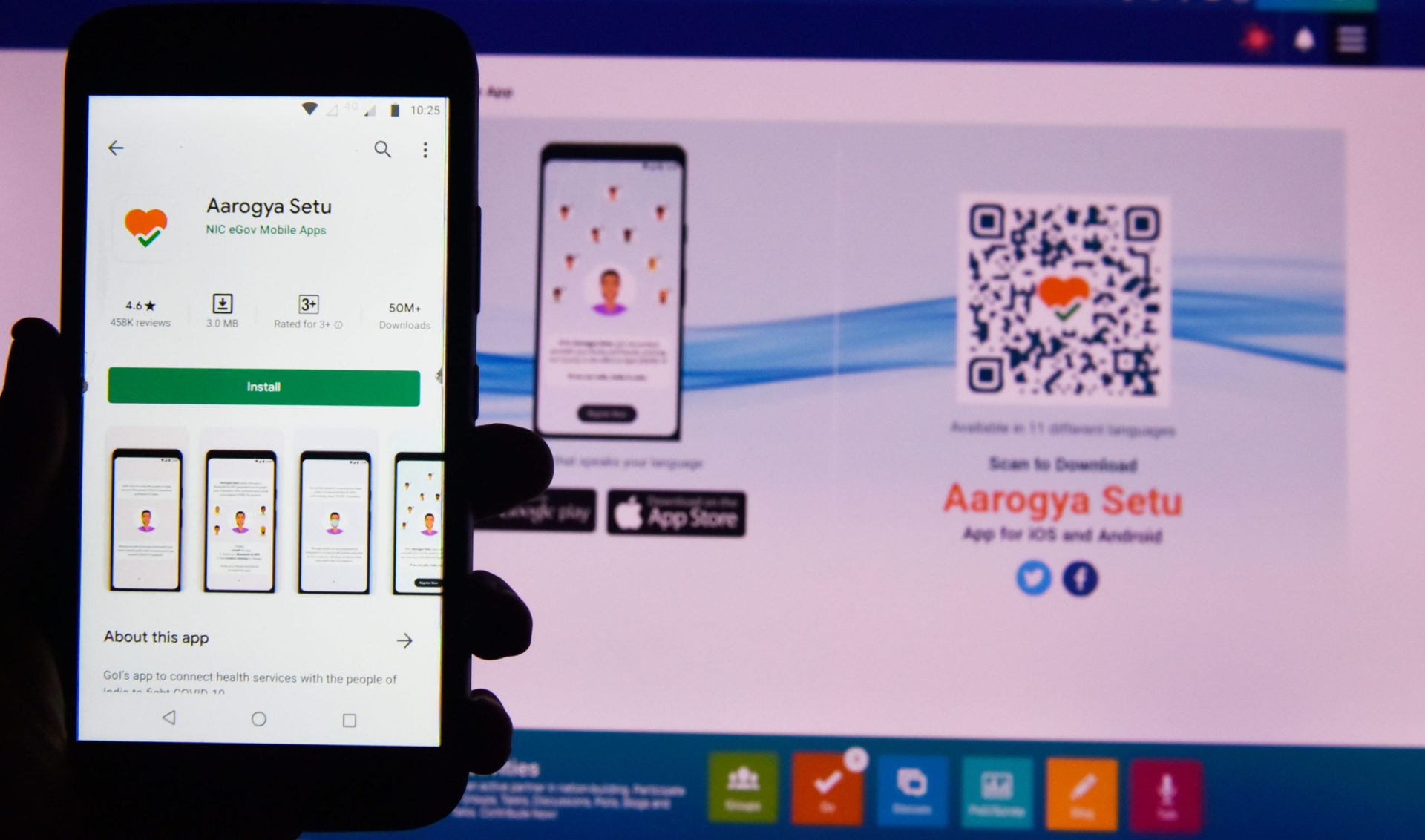

It might explain both why Modi increasingly borrows from Putin’s playbook as he seeks to build India into a surveillance state and why he remains vulnerable to being stymied by committed opposition. A recent controversy over a cybersecurity app that the Modi government tried to mandate be pre-installed on every new smartphone sold in India – a country with a billion smartphone users – exemplified this tension.

Modi and Putin’s parallel surveillance states

“Today, your phone is like your house in your pocket,” says Apar Gupta, a lawyer and founder of the Delhi-based advocacy group Internet Freedom Foundation. He was responding to news this week that the Indian government had directed companies such as Apple, Samsung and Xiaomi to pre-install Sanchar Saathi (literally, Communication Partner), a state-owned cybersecurity app on all new smartphones. Effectively, Gupta said, the “government is putting its own lock on your house.” And it gets to keep the key. The Indian government’s directive is very similar to one from the Kremlin in August to pre-install its Max messenger app on all smartphones. Max, the Kremlin said, was a necessary anti-fraud measure to protect vulnerable Russian citizens. On September 1, it became mandatory for the Kremlin’s Max messenger app to be pre-installed on all smartphones. Now officials warn they might ban WhatsApp altogether for failing to prevent “crime and fraud.”

Just as Max gives Russia the tools to effectively spy on all of the people all of the time, opposition politician Priyanka Gandhi described the Modi government’s Sanchar Saathi as a “snooping” app. “It’s ridiculous,” she said. “Citizens have a right to privacy.” Criticism has focused on the mandatory nature of the app and a secretive process in which no prior public discussion was had before companies were ordered to install the app. The government has rejected the idea that Sanchar Saathi can be used for surveillance purposes. In 2024, it pointed out, Indians lost over $2.5 billion to cyber scams that take advantage of the widespread adoption of digital services in India and the abundance of data available online. Internet freedom advocate Nikhil Pahwa says that the Indian government has been notoriously lax about protecting citizens’ data and is responsible in large part for creating the problems it claims to be fixing with the mandatory state-owned cybersecurity app.

Even as it gave itself carte blanche to access citizens’ data, the Indian authorities this month also implemented stricter rules governing data privacy. The rules demand more accountability from Big Tech, for companies to minimize the collection of personal data and to give users a clearly-marked option to not share data. Its language about consent and individual privacy borrows heavily from Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation. The GDPR is the basis for much of the regulation around the world, from Brazil to South Korea and Canada. Currently, some 144 countries have national data privacy and protection guidelines in place.

Among the few holdouts is the U.S., where individual states have been setting up rules that sometimes clash with federal priorities. One of those priorities is to weaken GDPR. Last week, in Brussels, Howard Lutnick, the U.S. Secretary of Commerce, said that if the EU “take their foot off this regulatory framework” it might lead to increased investment. “Let’s settle the outstanding cases against Google, and against Microsoft, and against Amazon. Let’s put them behind us,” Lutnick said as he also dangled the carrot of reduced tariffs. The EU has already proposed a ‘Digital Omnibus’ package that waters down the GDPR’s rules on individual data privacy and freezes AI regulation.

An argument the Indian government’s supporters, including many in the media, used to defend the mandatory pre-installation of a state cybersecurity app was Big Tech’s vast, revenue-generating data crawls. It is an argument that strikes at the heart of digital sovereignty, an increasingly popular phrase in the Global South, where countries are now insisting that tech giants store local data locally and share some of the profits. In May, Meta said it might have to cut Nigerian users off from their Facebook and Instagram accounts after the government fined parent company Meta nearly $300 million for violating data protection laws. It’s the kind of action that is now leading the U.S. government to negotiate trade deals with countries—most recently with Malaysia and Indonesia—that require them to refrain from taxing Silicon Valley profits or requiring them to invest in the local digital ecosystem.

Defending the need for digital sovereignty, the Indian politician Shashi Tharoor wrote recently that “self-respecting and self-reliant” countries must insist on “unhindered rights to regulate the national digital space” or risk “cementing digital vassalage.” In October, the California governor Gavin Newsom signed a bill that requires companies to make it easy for Californians to opt out of data sharing, a right that Californians retain even when traveling thus forcing tech companies to consider making it a national option in order to comply with the law. But, as digital rights campaigner Nikhil Pahwa says, while India’s Data Protection Law “will make private companies more accountable, it makes the Indian government less accountable.”

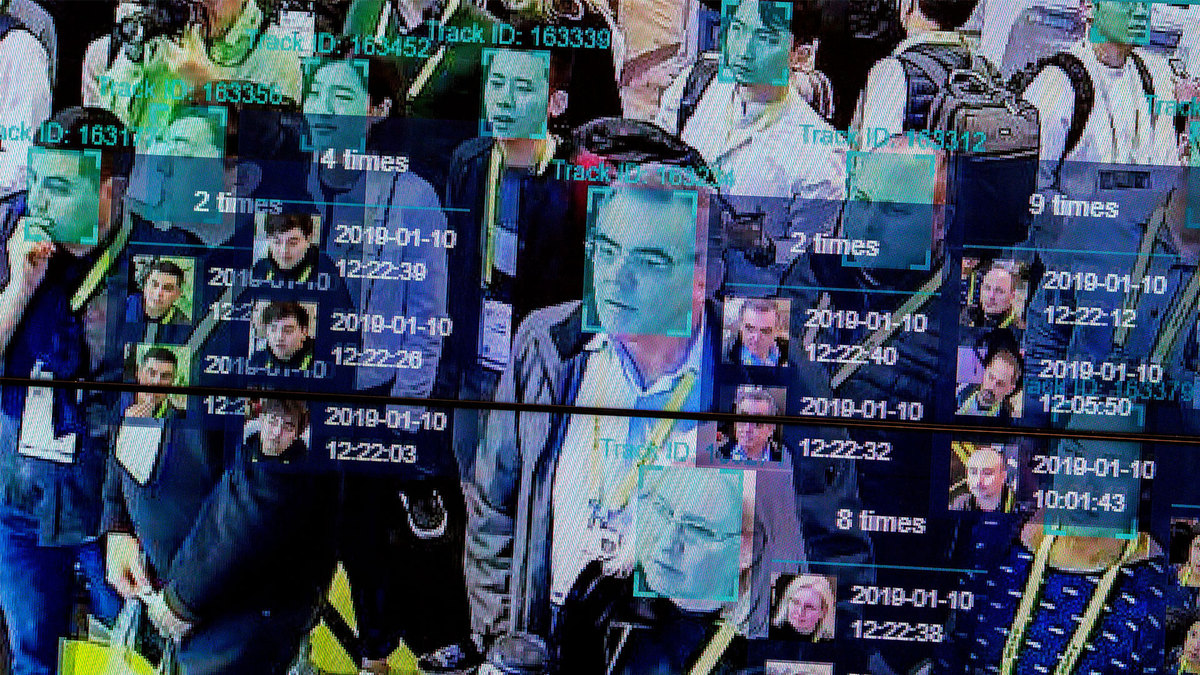

India is the first country to attempt to follow the Russian lead in having a state-run app pre-installed on all smartphones. The next steps, the Russian example suggests, are significantly more alarming. In Russia, schoolchildren will now have their faces scanned as they enter school buildings. Their data will be added to the national ‘Unified Biometric System,’ which already holds the details of over 50 million Russians. The project, which authorities have said is “voluntary,” is expected to cost over $600 million. And by 2030, the Ministry of Digital Development estimates that there will be five million government-run surveillance cameras across the country, all hooked up to an AI system with facial recognition capabilities. By 2021, some reports already ranked Delhi as the most surveilled city in the world. And the Indian government has a history of using spyware to keep tabs on opposition politicians, civil society organizations and journalists.

So even as the Indian government backpedals on Sanchar Saathi, its very existence was a warning that digital privacy and sovereignty doesn’t necessarily mean more rights for people. It could just mean a power grab by a national government, particularly one that takes its cues from Putin’s Russia.

A version of this story was published in this week’s Coda Currents newsletter. Sign up here.