On August 7, 2008, Maguli Okropiridze, almost nine months pregnant, fled her village of Ergneti in the Georgian region of South Ossetia.

For Maguli, who had become used to a life lived in the backdrop of bullets and artillery shells, it took a week of heavy shelling to push her out of her home. She had finally decided to flee what was now a war zone. But the stress of evacuating herself and her four children sent her into labour. With just a quarter of an hour to go before midnight, in a hospital in the small nearby town of Gori, Maguli gave birth to a baby girl, Keto.

Just two days later, on August 9, Russian planes began bombing Gori. Maguli, still dressed in a hospital gown, grabbed her newborn daughter and, without hesitation, jumped out of the second floor window.

“Keto is as old as the war”, Maguli told me. “Every year on her birthday, I first mourn and then I congratulate her”.

Like Maguli, many Georgians believe the war began on August 7, when Russian troops crossed into South Ossetia. In Moscow, the start of the war is said to be August 8, when Russian troops apparently responded to Georgia’s shelling of Tskhinvali, 30 kilometers from Gori and now the capital of disputed South Ossetia. But Maguli’s own government disagrees with her.

In the ruling party’s version of events, the Russo-Georgian war broke out on August 8, just as the Kremlin says.

A day’s difference might seem minor, but it flips the script. It reverses the roles between victims and perpetrators. It changes how Georgians will describe the war to future generations. And it calls into question the national memory and, in part, Georgia’s national identity.

When I was 10-years-old, wondering why fighter jets were hovering in the skies above us, my grandmother told me that Russia had invaded Georgia and annexed 20% of the country. I’d stand behind her chair, as the women gathered in her kitchen would curse Russia between sips of tea. Many had sons who were on the front line. These women, whose words I absorbed, are now being told that it wasn’t Russia’s fault that their sons had to go into battle. Since 2012, when Georgian Dream came to power, the party has maintained that its predecessors brought the war upon themselves by provoking Vladimir Putin.

As recently as April this year, Georgia’s prime minister told a government-friendly TV station that the 2008 war was the fault of former president Mikheil Saakashvili, acting on orders issued by a shadowy, nefarious Western cabal. The Georgian government has authorized a public commission to investigate “the circumstances surrounding the start of the 2008 war in South Ossetia,” particularly the role of the former government, the party of war as Georgian Dream characterizes it, while referring to itself as the party of peace even as it has spent months brutally suppressing street protests since October last year.

My country is now effectively putting itself on trial, 17 years after suffering an invasion from a foreign force.

Georgia, a tiny country in the Caucasus region, wedged between eastern Europe and western Asia, has always been at a crossroads. For centuries, its location along the Silk Road brought both prosperity and peril, with invaders chasing the same riches that trade delivered.

For the past 200 years, the invader has been Russia. And resistance against those invasions has formed a core part of Georgian identity. “For us, the field in which we have lived is non-traditional and foreign,” noted the Georgian philosopher Merab Mamardashvili. This, he added, “is the field of Russian power which took shape, let us say, around the 17th century and reached its culmination under Soviet rule. The main idea of this field is that the state stands above all, and the person is nothing more than a servant of the state and of the state’s idea.”

The stories of Russian conquests and local defiance show up in textbooks, films, and casual dinner conversation not just as historical events, but as a lens through which the present is understood.

For much of Georgian society, the effort to preserve the memory of Russia’s past aggressions is about staying alert to patterns and remembering the lessons that help us make sense of what it means to live next to a former colonial master that never truly left. In the words of the writer Grigol Robakidze, “no one has inflicted as much harm – moral and intellectual harm – as Russia has.” The Russians, he wrote, “once they came to Georgia, immediately reached into the very soul of the Georgian people and set about corrupting it, erasing its uniqueness.”

It is this antipathy and foundational mistrust that the current government of Georgia must contend with as it sets about rewriting the story of the 2008 Russo-Georgian war.

At 27, I have lived under the same government for nearly half my life. And every protest I’ve ever attended against this government (and there have been many) has, in some way, circled back to Russia. The Kremlin’s reach, most protestors agree, extends to the highest levels of the Georgian government.

Georgian Dream emerged in 2012 as an alternative to the pro-western Saakashvili’s increasingly authoritarian rule. It had momentum and money to spend. Founded and funded by the oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili, who made his billions in Russia’s post-Soviet maelstrom, the party promised citizens democracy, stability, and integration into the European Union and NATO.

While many were wary of Ivanishvili’s intentions, given his background and ties to Russia, citizens were ready for change and his party emerged as the only viable option after absorbing much of the disjointed opposition.

The story of Ivanishvili’s authoritarian takeover is familiar across post-Soviet republics. A billionaire appears out of nowhere, cloaked in populist promises about creating wealth, stability, and in Ivanishvili’s case, giving away literal ‘free money’. He wins, and then begins to capture state institutions one by one. Only then does he reveal the long game – absolute power. By the time the public sees the full picture, the tools they might use to push back have already been taken away.

During its first term, and even for several years after, Georgian Dream largely maintained the appearance of a somewhat democratic, West-facing government. It was a necessary performance in a country where the overwhelming majority of citizens support Euro-Atlantic integration, and where openly pro-Russian politicians have had little to no chance of mainstream success.

My own doubts about Georgian Dream started around two years into its rule. I was 17, interning at a fact-checking organisation. It was 2015, the year when Russia’s ‘borderization’ policy was at its peak.

Borderization was a euphemism for what was basically a land grab, the slow but inexorable expansion of Russian territory within Georgia. Russian forces, often in the middle of the night, would move fences or put up new “border” signs, inching the occupation line further into Georgia. Sometimes it was a few meters, sometimes more. Either way, people would lose access to their farmland, water, and sometimes wake up to a completely different reality, with their house now inside occupied territory, unable to access the ‘Georgian side’.

One day, I was tasked to fact-check a quote from then-Defense Minister, Tina Khidasheli. She said: “20% of our country is occupied, and if Russians move the ‘border’ by two kilometers, it’s bad, but it’s also just a continuation of the same political line that has been happening in the country for a long time.”

I remember being baffled by this. For two reasons. First because she referred to the occupation line as a border. If you call the occupation line a border then you’re legitimizing it, you’re going along with Russia’s talking points. And second because she made it sound like moving the line by two kilometers was nothing, but try telling that to the people who went to bed in Georgia and woke up in Russia, or at least subject to Russia’s rules..

This was my first sign that the government was softening its stance on occupation. But folks older than me remember pro-Russian rhetoric surfacing even earlier.

For instance in 2013, Ivanishvili claimed Russia was not, in his view, an imperial nation interested in rebuilding its empire.

“I don’t think and I don’t believe that Russia’s strategy is to conquer and occupy the territories of neighboring countries. I don’t believe that,” he told an interviewer and then went on to boast about his superior analytical skills.

The same year, he spoke of forming an “investigative commission” on the causes and triggers of the 2008 war. In 2018, during the presidential election, the Georgian Dream-backed candidate, Salome Zurabishvili claimed that Georgia had started the 2008 war and even suggested the previous government may have struck a covert deal with Russia.

In the face of a swift backlash from the public, most Georgian Dream politicians either avoided commenting on the matter or distanced themselves from Zurabishvili’s remarks. Tea Tsulukiani, the Justice Minister at the time, even said: “Georgia’s position is singular and unchanged: it is the position we present in Strasbourg and at The Hague: that Russia started the war against Georgia.”

But in the years that followed, that “singular and unchanged” position would very much change.

While the international community eventually understood Russia’s 2008 invasion of Georgia to be a dress rehearsal for the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 – a connection the world failed to heed in 2014 – Tbilisi took the opposite tack. On the international stage, criticism of Russia was avoided, and Georgian officials blamed NATO’s eastern expansion for provoking Moscow into war.

Back home, Georgian Dream doubled down on a worldview seemingly lifted straight from the Kremlin.

In this world, every critic, every opposition party, and every Western-backed NGO or media outlet was just another node in a vast international plot. Georgian Dream officials and affiliated media claimed that the entire opposition was controlled by Saakashvili and his party, the United National Movement, which took its orders from a “global war party” run by elites in Brussels and Washington.

The goal? To create a submissive regime in Georgia which would realize the elites’ covert plans to drag Georgia into war with Russia and open another front in a perpetual war against the Kremlin. On the civic front, these same Western elites were working to erase Georgian culture — to undermine the church and traditional values, and to advance a “liberal ideology” which includes “gay propaganda.”

Georgian Dream, rather like Vladimir Putin does for the world at large, casts itself as the last line of defense in Georgia, a guardian of peace and sovereignty and traditional values. And for these reasons, they claim, the West, particularly the EU, wants them gone.

And while the phrase “global war party” originated in Russian propaganda, similar rhetoric is part of a wider, international authoritarian playbook. When Georgian Dream saw a familiar narrative about globalist elites gaining ground in Donald Trump’s America, it rebranded its “global war party” as the “deep state”. Soon after, soundbites from U.S. politicians began appearing regularly in propaganda outlets.

In the run-up to the 2024 parliamentary elections, Georgian Dream’s central promise was peace with Russia. Fearmongering about war saturated the media landscape. And this is when the narrative turned once again to 2008.

Party officials said that the same Western cabal that had manipulated Saakashvili into war with Russia was at work again. Georgian Dream campaigned on prosecuting Saakashvili for his “well-planned treason”. Then, Bidzina Ivanishvili declared that Georgia should apologize for the war.

This story became central to the state-sanctioned version of recent history, one in which Russia was recast not as the aggressor, but as a misunderstood neighbor. And Saakashvili was not a flawed leader defeated in elections, but a Western puppet. And the 2008 war not as an invasion, but a provocation.

Given the violently contested election results and rampant allegations of fraud, it’s hard to measure how effective Georgian Dream’s historical revisionism was. But in December 2024, a large part of Georgian society made its position clear: when Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze announced Georgia was halting its EU accession negotiations for four years, the response was immediate.

Outraged, Georgians flooded the streets demanding a reversal of the decision in what became the largest protests in the country’s modern history.

The government responded with an unprecedented crackdown.

In just six months, the no longer independent courts passed reams of repressive laws, citizens were brutally beaten by police not only at the protests but also on their own doorsteps, and attacks on independent media and civil society organizations intensified. More than 60 political prisoners now face long jail terms, and at least eight prominent opposition politicians are already behind bars.

Yet, while the already tight authoritarian screws in Georgia have been further tightened, Ivanishvili has not yet engineered a full ideological takeover. The battle over Georgia’s minds and collective memory is still being fought.

For more than 250 days, Georgians have been fighting to preserve their versions of the truth and for their visions of the country’s future.

The view outside my windows in Tbilisi reflects that fight. In just the last year, the building in front of me now features a portrait of Maro Makashvili, a teenage nurse killed in the 1921 Soviet invasion of Georgia. A neighboring building features a mural of Giorgi Antsukhelidze, a Georgian soldier tortured by Russians during the 2008 war. And a third building features Georgian and Ukrainian flags.

This isn’t just a fight against authoritarianism for many of us. It’s the latest episode in a 200-year struggle against Russian imperialism and it’s a struggle for the rights of Georgians to write our past and, by extension, our future.

As the 2008 war once again became a staple of daily conversations, I found myself drawn into discussions about assigning blame. What surprised me most was hearing even those who regularly protest against the government repeat Georgian Dream’s official talking points about the conflict.

It left me wondering if I was misremembering the war, or if there was an actual coordinated effort to rewrite the past.

We tend to think of rewriting history as reinterpreting distant events, reworking details buried in time to fit a particular cultural or political moment. But what does it mean to reshape the memory of a war that nearly every Georgian remembers?

I set out to answer two questions: What really led to the 2008 war? And how deeply has Georgian Dream’s version influenced the national memory? I spoke to former government officials, international experts, and, most importantly, the people living along the occupation line – those still living with the war’s consequences day in and day out.

My first stop was Kirbali, a village notorious for being a focal point of Russia’s borderization policy, including the kidnapping of residents. Here, the occupation line is mostly invisible, there is no barbed wire, fence, or natural boundary, it’s only marked by occasional signs, making it largely impossible to know where the line is actually located.

This is deliberate. It sets up Russia’s so-called “kidnapping” tactic—with Georgian citizens allegedly snatched from their land to sow fear among the population and pressure whole communities into abandoning their homes, clearing the way for borderization.

In a village as small as Kirbali, outsiders don’t go unnoticed. As soon as I arrived, the police flagged my car. They asked about the purpose of my visit and insisted that a patrol vehicle accompany me wherever I went.

Authorities knew whom I spoke to and which homes I entered.

I started by heading to the central square. The first thing you see is a portrait of Tamaz Ginture that appears to float in the sky. He was shot and killed by Russian troops in 2023 while attempting to visit a local church. Right below the picture, people gather to chat and play dominoes or backgammon. But as soon as I mentioned the 2008 war, their openness vanished. Most refused to talk. Two men who were willing to speak simply parroted government propaganda.

After an hour, one man who had initially brushed me off quietly invited me to his home for a coffee.

“Everyone’s afraid to talk,” he told me as soon as we sat down. “You won’t get any answers out there.” His wife nodded in agreement, as she set the table.

He explained why: one of the men I’d spoken to in the square was a Georgian Dream coordinator. No one dares to contradict the party line when he’s around.

These “coordinators” are informal, sometimes semi-formal, representatives of Georgian Dream. They’re local operatives embedded in public institutions who help the party monitor communities, manage voter turnout, and shape opinion. In election season, they mobilize supporters. Outside of it, they track who says what.

The fear they instill is real, especially in rural and tight-knit communities. Speaking out can mean losing government benefits, being fired from a public-sector job, or, in some cases, facing physical threats.

That’s the setup in most villages. But in Kirbali, the constant police surveillance made it even harder to get people to chat, to reveal their thoughts or opinions. A patrol car followed my every step.

So I moved on to Ergneti – the first village Russians troops crossed when they entered undisputed Georgian territory. It’s also where a river overlaps with the occupation line, meaning fewer kidnappings and less police presence.

It gave me a little more space to listen and for others to speak.

Around much of the world, the 2008 Russo-Georgian war came to be known as the “five day war”, the fighting taking place from August 7 to August 12, when a ceasefire agreement was brokered by the French President Nicolas Sarkozy.

But in Georgia, people don’t often refer to the “five-day war”. Here, the war did not feel like it lasted only five days. All the chaos, death and suffering of war were not contained in just those five days.

While the term captures the war’s most intense phase, it flattens the reality on the ground. It erases the escalation that preceded August 7, and the devastation that continued after the ceasefire was signed – when Russian and Ossetian forces looted villages, set homes ablaze, and remained on uncontested Georgian territory for many more weeks.

For those living along the occupation line, the idea that the war lasted only five days is absurd. When they speak about the war, their timelines stretch far beyond a single week – and often, far beyond 2008.

“We have been living with this war for 35 years now,” Nadika told me as she showed me the occupation line from her window. “Many first heard about guns being fired in 2008 and the first bomb was a shock. But that was nothing new for us,” she added.

Nadika, now in her 50s, has spent her entire life in Ergneti, a village that borders Tskhinvali, the de facto South Ossetian capital. Today, Ergneti is eerily quiet. The closer you get to the occupation line, the more houses you see standing empty. Nadika and Maguli live in the strip closest to the line, their families among the few who remain. Ergneti has no shops or pharmacies, and many residents commute to Tbilisi for work.

Only one bus runs twice a day, covering several villages on its way. It often starts full, with people sitting on makeshift chairs, but few passengers make it all the way to Ergenti where the last stop is right in front of the Georgian patrol post. Before the 2008 war, Ergneti was not a ghost town even though for Nadika, Maguli and other residents, gunfire and shelling were so frequent they became part of the day’s sounds, like a rooster crowing in the morning. It’s why Nadika doesn’t talk of 2008 alone, when she talks about the war. She traces it back to the Soviet Union’s collapse and the wave of violence that followed in its wake, culminating in the 1991 war between Georgian government forces and Russian-backed South Ossetian separatists.

Others trace it back even further.

On the one bus that takes you to Ergneti, I met Tamara Kviginadze, a soft-spoken philologist in her 60s who grew up in Tskhinvali. She travels to Ergneti almost every week to visit the graves of her parents who wanted to be buried close to their hometown, Tskhinvali.

For her, the war began in the beginning of the 19th century, when the Russian Empire first arrived in Georgia.

By the end of the 18th century, Georgia was a fractured land. In the west, minor kingdoms operated under heavy Ottoman influence. In the east, King Erekle II had recently managed to shake off Persian rule, taking advantage of a succession crisis in the Qajar dynasty. But he knew the peace wouldn’t last. With another Persian invasion looming, Erekle had few options. He sent appeals to Europe. No one answered. The only door left open was to the north. Russia, then expanding southward, presented itself as a Christian ally and protector.

So, in 1783, Erekle II signed an agreement with Russia. Moscow promised to safeguard Georgia’s independence and territory. Georgia, in return, renounced any allegiance to Persia or the Ottoman Empire.

On paper, the deal seemed beneficial to Georgia but when the Persian army came marching, there were no Russian troops in sight. And when the smoke cleared, Russia came, not to help, but to annex. By 1801, Georgia was no longer sovereign.

For the next two centuries, Georgia only managed to gain independence only once: in 1918, after the Russian Empire crumbled. Its independence lasted just three years.

That year, 1918, also marked the first outbreak of violent clashes between the Georgian army and separatists formations in the regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

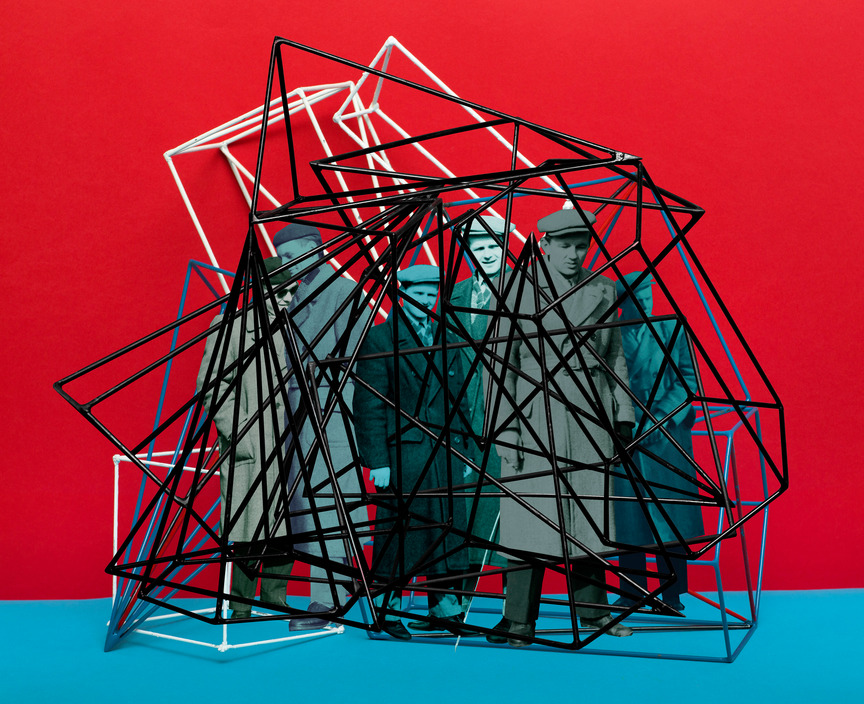

After the February Revolution in Petrograd in 1917, which precipitated the end of the Romanovs, Ossetians and Abkhazians set up National Councils which advocated for the creation of organs of self-rule in Abkhazia and Ossetian-inhabited areas. The councils in both regions, dominated by Bolshevik ideology, became deeply intertwined with Bolshevik forces inside Soviet Russia.

For the Georgian authorities, these uprisings were viewed not as a fight for autonomy, but as a Soviet-backed attempt to destabilize the fragile new republic. The Georgian army eventually crushed the rebellion, but the violence left deep scars, fueling a legacy of mistrust and ethnic tension. The victory was also short-lived. In 1921, the Red Army invaded from the north and the country was forcibly absorbed into the newly forming Soviet Union. The promise of independence was snuffed out, replaced by 70 years of authoritarian rule, during which the roots of many future conflicts, including the war in 2008, took hold.

“The empire has one rule,” Tamara told me on the bus. “Divide, indoctrinate, rule. That’s it.”

After the Soviet Union collapsed, Georgia’s first decade of independence was defined by economic ruin, crumbling institutions, and civil war in the streets of Tbilisi. A newly independent nation was rejecting its former master and looking towards the West for protection.

In Abkhazia, separatists emboldened by Moscow started calling for independence. In South Ossetia, the goal was unification with Russia. “By the late ‘80s,” Tamara told me, “you could feel it changing – when it came to politics, we were divided.” She recalls Ossetian militias appearing in Tskhinvali around 1988.

In Tbilisi, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, a former Soviet dissident, came to power. As demands for autonomy grew, so did his nationalistic rhetoric. By 1990, in Tskhinvali, ethnic tensions were rising. Tamara’s family now slept with their suitcases packed.

“They started marking Georgian houses with a Z – just like in Ukraine now,” she told me as she recalled her encounter with a young Ossetian boy who came to her with a warning: “He told me that he was at the base and overheard a conversation about which Georgian families were in line to be terrorized.” Seal the windows, Molotovs are coming, he said and left.

Soon, South Ossetia declared independence, Gamsakhurdia responded by revoking its autonomy. A year-long war followed. Over 1,000 people lost their lives and tens of thousands were displaced, including Tamara’s family who are still unable to go back to their home.

Abkhazia saw even more devastation. The separatists captured Sukhumi in 1993. The war left 10,000 dead and over 250,000 Georgians ethnically cleansed – one of the largest population displacements in the post-Soviet space.

Just like in 1921, the support for separatist movements came from Russia but this time, it played the roles of both arsonist and firefighter: arming separatists, providing air support, and deploying irregular fighters who would later become a staple in Russia’s foreign wars, all while offering to broker peace.

By the end of 1990s, Georgia ended up with two breakaway regions, and Russian peacekeepers on the ground.

Meanwhile in Tbilisi, a political transformation was underway. In 2003, mass protests – known as the Rose Revolution – toppled the old regime and brought Mikheil Saakashvili to power. Young and U.S.-educated, Saakashvili was a reformer with a clear message: Georgia would no longer orbit Moscow. Instead, it would pursue modernization, with EU and NATO membership as the ultimate goal.

Russia hit back. It banned key Georgian exports, cut gas supplies, and illegally deported thousands of Georgian migrant workers. On the ground, it expanded support for the separatist regimes, quietly increased its military presence under the cover of peacekeeping and issued Russian passports to their populations, a move that would later enable Moscow to claim protection of Russian citizens as a pretext to invade Georgia.

In 2007, Vladimir Putin stood before an audience of Western leaders in Munich and delivered what many thought was a theatrical outburst. He railed against U.S. hegemony, accused NATO of encroachment, and warned that a unipolar world was unacceptable. The speech was blunt – but few in the West took it seriously. Instead, it was viewed as a nostalgic rant from a former KGB man still mourning the Soviet collapse.

But the Kremlin wasn’t bluffing. The Munich speech was a statement of intent. And the West’s underestimation turned out to be a strategic miscalculation.

By mid-2008, Russia was in a position of unusual strength. Oil prices were soaring. European states – particularly Germany, France, and Italy – were deeply entangled in energy deals with Gazprom.

In Washington, George W. Bush’s presidency was limping to an end. His foreign policy legacy – Iraq, Afghanistan – had sapped both credibility and political capital. Barack Obama, still a candidate, was already talking about a “reset” with Russia. The West wasn’t ready for a confrontation, and Moscow knew it.

While the Baltic states and some Eastern Europeans were sounding alarms about Russian aggression, Western Europe remained fixated on maintaining business as usual.

Russia, though imperfect, was still seen as a partner – a regional power with whom the West could reason, negotiate, and, when needed, do business. Against that backdrop, Georgia’s young, Westward-looking president was easier to caricature. Saakashvili’s warnings of further Russian aggression were brushed off as alarmism.

So when war broke out in August 2008, that pre-existing perception – a stable, reactive Russia versus a hot-headed, unpredictable Georgia – shaped how the story was told. Western media fixated on the question of who fired the first shot, not who had laid the groundwork or moved troops into another sovereign country. And Western leaders, unwilling to jeopardize fragile ties with Moscow, leaned into the narrative that Georgia bore at least partial blame.

This mindset shaped the “Tagliavini Report”, the EU’s official post-mortem on the war written by a team led by Swiss diplomat Heidi Tagliavini and published in September 2009, just over a year after the war. While the document acknowledged years of escalating provocations, Russia’s disproportionate use of force, and the presence of the Russian army in Georgia prior to August 8, it also placed significant responsibility on Tbilisi for launching the first full-scale military assault on Tskhinvali. It was a legal framing that ignored the broader political climate – in which Russia had been undermining Georgian sovereignty through proxy forces, passportization, and military buildup for years.

The result was a narrative that satisfied diplomatic caution: both sides bore blame, so the West wouldn’t have to choose. And by the time Russian troops settled into new military bases deep in Georgia’s breakaway regions, the world had already moved on. Obama went on to push the ‘reset’ button, while EU countries continued selling military equipment to Russia, some of which would later appear on the frontlines in Ukraine.

Subsequent reporting and analysis would complicate that picture with Western analysts later publishing satellite images that appeared to support Georgia’s timeline, showing large Russian convoys already moving through the South Ossetian mountains on August 7. But first impressions are hard to shake. For many outside observers, the image of Georgia shelling a breakaway capital – regardless of the context – became the war’s defining moment. That framing, cemented in early news coverage and echoed by the Tagliavini report, continued to shape international opinion.

The international view of the 2008 war shifted only after 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and backed separatists in eastern Ukraine. Suddenly, Georgia was seen less as an isolated case and more as a test run. Yet even this re-examination was half-hearted. It wasn’t until Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 that the implications of Russia’s actions in 2008 became impossible to soft pedal.

Governments that had once blamed both sides for the Georgia war now spoke of “patterns”. Think tanks drew direct lines from the Roki Tunnel to the Donbas. Many experts in the West now saw 2008 as the opening move in a long campaign of revanchist warfare. But while the international community was re-contextualizing 2008 as the beginning of something larger, Georgia’s own government was trying to prove otherwise. Georgian Dream has organized what they call a “Nuremberg trial” in Georgia that will show that it was the previous government, in other words the Georgian state, which bears primary responsibility for starting the war.

For hours on live TV, retired generals and ex-officials have been grilled on minute details, on exact locations, timelines, on who participated in what meeting. Each session was packed with people spewing dense detail about military plans and discussion inside the corridors of Georgian power at the time. The questions being asked appeared laced with accusation and insinuation. The aim seemed to be to lay the blame squarely on Saakashvili and his allies, while also absolving the military of guilt.

Several politicians who refused to attend the hearings have been arrested.

For now, it seems the government’s efforts are already paying off. On what is now the 17th anniversary of the war, people remember those five days in starkly different ways, shaped not just by their lived experience but by competing narratives.

Nadika remembers the shelling and the chaos. But her memories are laced with suspicion. She’s come to believe that the war was staged; part of a plot by Saakashvili’s government. “They were bought off,” she says. “From the very first day, they were on TV boasting about how the army took this village or that one.” She thinks Georgia provoked Russia, maybe even invited the invasion. “Why did the commanders run?” she asks me, citing a conspiracy theory that is not rooted in any evidence. More recently, she’s begun echoing another popular Georgian Dream line: that the West once again tried to pull Georgia into another war in Ukraine. “They were pushing for a second front,” she says. “Even Ukrainians were calling on us to join.”

But not everyone in Ergneti buys into that version. Maguli, who gave birth during the bombardment, says she has no loyalty to Saakashvili, but she remembers who shelled her town. “I’m not a supporter of this government or the previous one,” she says. “But I had to jump out of a hospital window with my hours-old baby while the town was being shelled. And I’m still the one to blame?” She wants peace but not historical revision. “I can’t go along with people rewriting history,”she tells me, adding that she’s been trying to bring together historians, researchers, and neighbors to revisit what really happened.

Tamara, meanwhile, outright rejects the notion that Georgia could have started the war. “How can we be the ones to start a war on our own land, while bombs are falling and the [Russian] army is invading?” she asks, incredulous. She remembers, she tells me, what she saw, what she witnessed happen – bombs going off and Russian soldiers crossing into Georgia on August 7.

Three women. Three versions of the same war. Three memories shaped by where they lived, what they lost, and increasingly what they’ve been told happened. Their stories show how even recent history can splinter under the weight of competing truths. Their stories show how collective memory can be pulled in competing directions by politics, fear, and the calculated reconstruction of events long after the bombs stop falling.

Authoritarian leaders have long understood the power of history. It is by recasting the past that authoritarians reinforce their hold on the present and even the future.

While the details of stories differ, the playbook is often the same: simplify the past, claim things were once great until the bad people ruined it. For Georgian Dream, it is the previous government that brought the 2008 war with Russia to Georgia. But its narrative has the effect of blaming Georgia as a whole for poking the bear.

I spoke to the American historian, Timothy Snyder, who has long warned of the authoritarian tenor and tone of Donald Trump’s presidency. Referring to Georgian Dream’s version of the 2008 war, he said: “The problem with the story is that Georgia is not really the subject. The story is about how Russia is innocent and how poor Russia was provoked by Georgia. This is not a native authoritarian phenomenon, but a foreign one being reproduced as a native story.”

So how does this story benefit Georgian Dream? The most common explanation is that they are using their version of the past to discredit local rivals and prolong their rule. If Russia is rational and only violent when provoked, then Saakashvili’s government appears irrational, reckless, and responsible for the war. And remember, in Georgian Dream’s political rhetoric, all opposition to it is affiliated with Saakashvili.

But it’s hard to believe that this is the entirety of Georgian Dream’s intent. To me, the larger goal seems to be dismantling anti-Russia sentiment in Georgia – a goal that’s reflected in other attempts at rewriting history.

Take, for example, the ruling party’s adoption of a new political icon: the 18th-century king, Erekle II who signed a treaty with Russia that effectively led to Georgia’s subjugation.

Since 2022, Erekle’s name has been intrinsic to Georgian Dream’s slogans. And a statue of Erekle II is set to rise on the Kakheti Highway, near the headquarters of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Erekle is being celebrated as a symbol of pragmatism, a savior of Georgian Christianity, and proof that alignment with Moscow is Georgia’s historic path. But Georgian Dream ignores Erekle’s pro-European efforts, until he felt he had little choice but to turn to Russia for protection from Persia, and Russia’s betrayal of that very treaty.

Another example is the rewriting of the April 9 tragedy in 1989, when Soviet troops violently suppressed a peaceful Georgian protest, killing 21 people. This year, the government’s official statement replaced the word “Russia” with “foreign power,” the term officials often use for the West. Putin’s Russia, the argument seems to be, must not be conflated with the Soviet Union.

But why might some Georgians go along with the idea that we started the war?

Because memory is fragile. Every time we recall the past, we reshape it, filter it through what we’ve heard, what we’ve lost, and what we choose to believe. Repeated messages from those in power can overwrite what we thought we knew. Even if it’s victim-blaming on a national scale. “No one, no serious future historian is ever going to contest that Russia invaded Georgia, or Ukraine,” Snyder told me. “But if you can make it hard for people to say basic truths, because you have another big narrative in the mix, then you make it hard for people to recognize one another.”

Tamara, whom I met on the bus to Ergneti, said something about this collapse of shared reality that continues to haunt me: “This is truly the feeling I have, that I’m walking around looking for a homeland inside my homeland. I need help because I feel lost.”