There was nothing special about the scenes from Edmonton: orderly lines of people in winter coats snaking across a snowy park, bare trees stark against a pale winter sky, the mundane choreography of civic participation playing out in a provincial capital most Americans couldn’t locate on a map.

Albertans queuing to sign a petition, even one to secede from Canada, could never compete for attention with the tragic, disorienting developments that filled the first long month of 2026: the ICE shooting in Minneapolis, Donald Trump’s bombastic threats to annex Greenland, and Canadian prime minister Mark Carney’s tense warnings from Davos about middle powers ending up “on the menu.”

But for those who’ve tracked how sovereignty collapses, these winter queues had an eerie resonance.

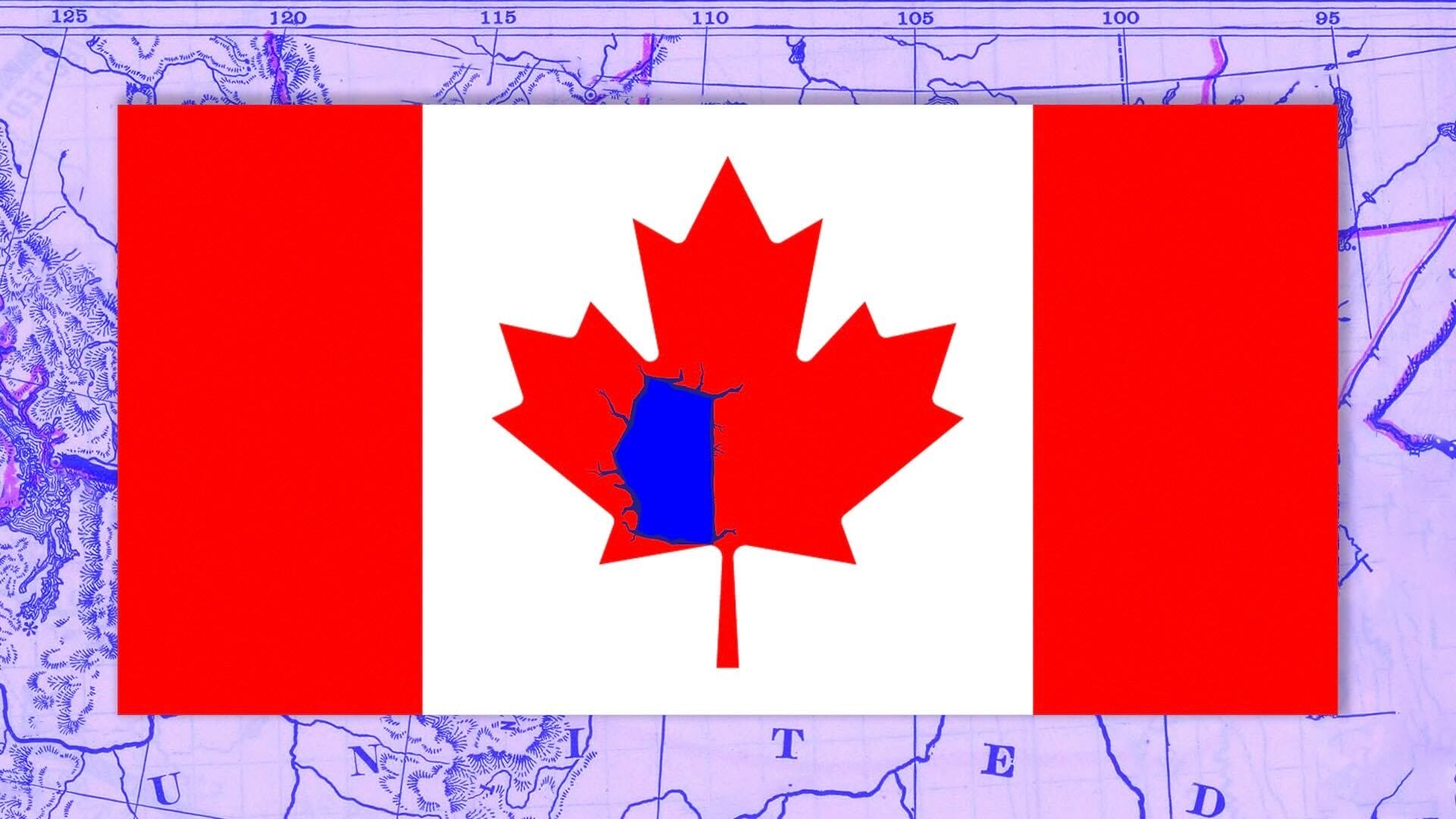

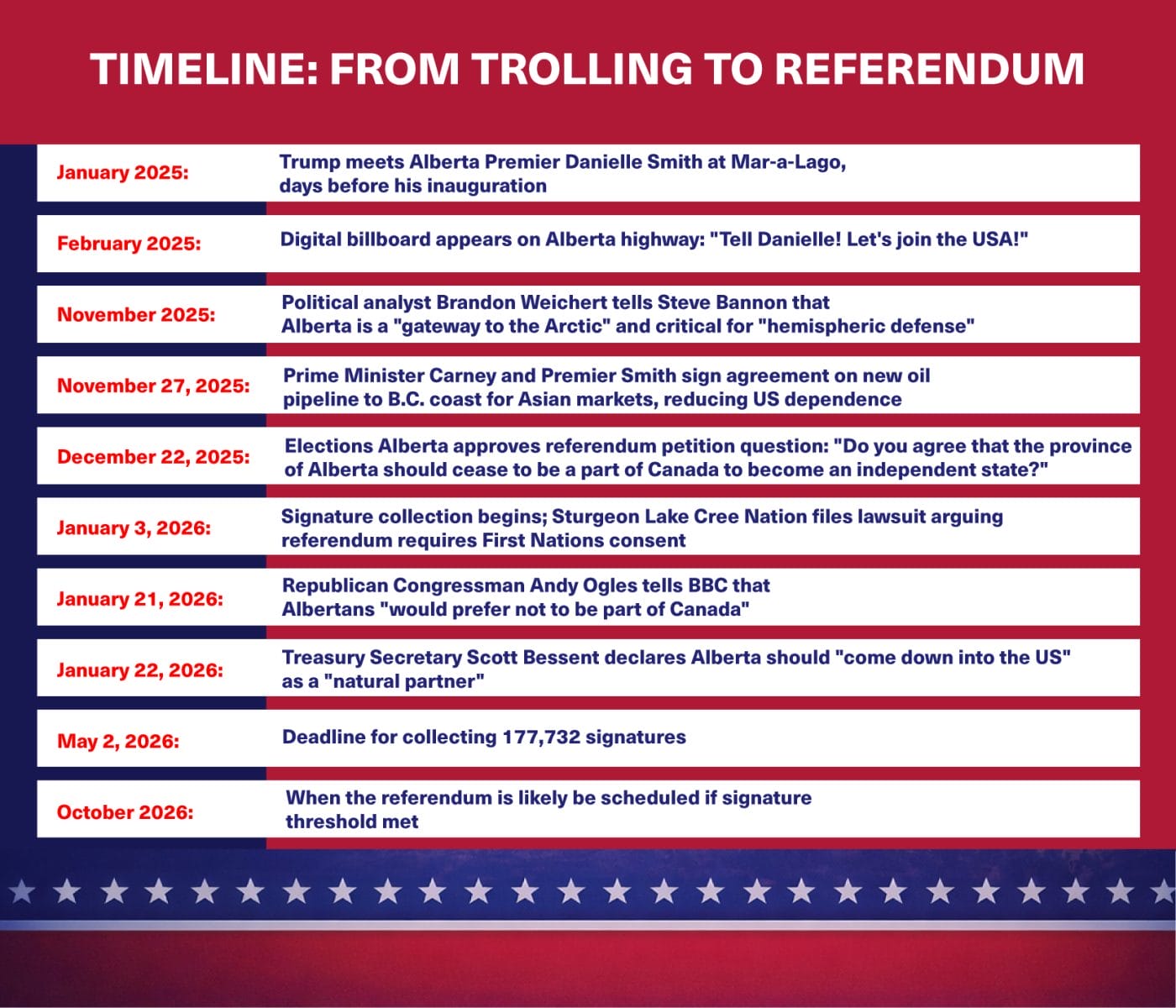

Almost as soon as he took office for his second term, Trump began calling Canada “the 51st state,” declaring that the country “only works” if it becomes part of the United States. He’d refuse to use proper titles, referring to Canadian prime ministers as “Governor Trudeau” and later “Governor Carney.” He posted altered maps showing Canada as U.S. territory. It played as crude humor, vintage Trump bluster designed to dominate the news cycle and unsettle an ally he viewed as weak. But by January 2026, as Trump’s threats to annex Greenland dominated headlines, his drip-drip taunting of Canada had calcified into something concrete on the ground in Alberta, had given shape and momentum to a once low-key secessionist sentiment.

The Alberta Prosperity Project needs 177,732 signatures by May to trigger a referendum on secession from Canada. Their representatives claim they’ve made “repeated visits” to Washington to meet with senior Trump administration officials, meetings they say took place inside the kind of secure facility reserved for discussing classified intelligence.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent publicly declared that Alberta should “come down into the U.S.” as a “natural partner.” Republican Congressman Andy Ogles told the BBC that Albertans “would prefer not to be part of Canada and be part of the United States because we are winning day in and day out.” According to the separatists’ own materials, their vision includes a “common market” with the U.S., zero tariffs, adoption of the U.S. dollar and construction of two oil pipelines through American territory. Spokesperson Jeffrey Rath has claimed the U.S. would potentially provide a $500 billion line of credit to the newly independent Alberta.

Widening the Overton window

A referendum on Albertan secession, should it happen, appears almost certain to fail. Polls show only 24% of Albertans support joining the U.S., with 65% strongly opposed. Most media outside Canada has treated this as a fringe story. But the language being used by the Trump administration in support of secession is becoming a textbook example of how the Overton window shifts: say the outrageous thing, let it be dismissed as mischievous troublemaking, and then watch as domestic actors race to occupy the newly opened political space. Repeat until the “absurd” becomes debatable, and the debatable becomes negotiable. When a U.S. Treasury Secretary publicly advocates for a Canadian province to secede and join America, he’s not predicting the future — he’s manufacturing a present in which such conversations become possible. There’s no master plan; the chaos itself creates opportunity.

The timing matters. Mark Carney has emerged as the strongest voice pushing back against Trump’s increasingly aggressive rhetoric, most notably in his Davos speech warning that middle powers risk ending up “on the menu.” Daniel Béland, a political scientist at McGill University who studies Canadian federalism, sees Alberta separatism as potentially serving a strategic purpose for the Trump administration: “Mark Carney is standing up to Trump. We saw what happened in Davos, right? So maybe they see that what’s happening in Alberta is weakening both Canada and Carney.”

The reason this story matters has less to do with the petition itself than with the narrative infrastructure being built around it. Recently, the exiled Russian news agency Meduza obtained a manual that the Kremlin had distributed to state-owned and pro-government media outlets instructing them how to cover Trump’s Greenland standoff. The directives were explicit: emphasize that territorial expansion is what “strong countries” do, that Trump is “aiming for Vladimir Putin’s success,” that conflicts with European countries “will be forgotten, but the territories will remain.” Journalists were told to frame NATO as “collapsing” and Putin as “forcing America to engage in equal dialogue” while European leaders “halfheartedly protest on social media.”

For Russian and Chinese state outlets, coverage of Albertan separatism is in keeping with the broad narrative that Western alliances are fracturing and sovereignty is negotiable for resource-rich regions. Former Trump adviser Steve Bannon, meanwhile, has spent the past year articulating what he calls a doctrine of “hemispheric defense,” framing Canada not as an ally but as territory that needs to be controlled. A “rapidly changing” Canada, he has said, in which 25% of the population is “foreign-born” means “these people are hostile to the United States of America.” Canada, Bannon claims, “is the next Ukraine.”

While Bannon has spoken extensively about hemispheric defence and Canada’s strategic value as a U.S. protectorate, there’s been no official movement towards such a goal — no Pentagon study, no Congressional authorization hearings, no legal pathway to annexation. Trump can troll, Bannon can theorize, Bessent can advocate, but no one appears to be seriously suggesting executing a plan. The damage isn’t in the doing, it’s in the destabilization, it’s in normalizing the conversation.

A parallel playbook doesn’t mean identical outcomes. There will be no little green men, no masked special forces in Calgary. But in 2014, when Russia entered Crimea, it wasn’t military occupation alone, it began with the systematic deployment of narratives that made annexation appear inevitable, even locally driven, before troops ever arrived. And now the Kremlin argues hypocrisy when the United Nations Secretary General says the principle of the “self-determination of peoples has a number of requisites.”

Déjà vu

My view is shaped by what I’ve witnessed: Russian-backed separatists taking over my grandparents’ house in Abkhazia in the 1990s, years of reporting from South Ossetia before Russia seized it in 2008, and standing outside a Ukrainian military base in Perevalnoe in 2014, watching Russian soldiers in unmarked uniforms take control while Moscow denied they were even there.

The annexation of Crimea showed how the ground for seizing sovereignty is laid through manufactured political theater. A politician whose party won 4% of the vote in 2010 was installed at gunpoint and held a referendum under occupation that reported 96.7% of people supported joining Russia. He’s still in charge.

Provinces and regions challenge sovereignty regularly. In Scotland’s 2014 referendum on whether it should be independent of the United Kingdom, nearly 45% voted ‘yes.’ Catalonia’s 2017 referendum saw 48% back independence from Spain before Madrid blocked it through force, both physical and legal. Quebec came within 1% of secession in 1995, a margin so narrow it prompted federal legislation defining how provinces could leave.

What distinguishes Alberta isn’t the referendum mechanism, it’s the involvement of a foreign power. In every previous case, challenges to sovereignty remained internal disputes. Spain’s government opposed Catalonia, but secessionists didn’t visit France to seek €500 billion in credit from the French government. Canada addressed Quebec’s grievances, but the U.S. Treasury Secretary at the time didn’t suggest that Quebec should “come down into the U.S.”

The overt encouragement of Albertan secession is without precedent among Western democracies. Canada faces provocation by a superpower neighbor whose cabinet officials actively encourage provincial secession, whose political figures meet separatist leaders in secure intelligence facilities, and whose state apparatus treats a G7 ally’s territorial integrity as negotiable. “This is something that, at least to my knowledge, is unprecedented,” says Béland, referring to US State Department meetings with Alberta separatists.

The architecture of erosion

The conditions in Alberta and Crimea are, of course, fundamentally different: no troops, no armed separatists, and Alberta is a democracy in which roughly 76% oppose joining the U.S., if not necessarily Albertan independence. What’s comparable though is the vocabulary being used in the U.S.: the systematic framing of sovereignty as conditional, resources as rightfully belonging to a more powerful neighbor, and local grievances as requiring external “solutions.”

The rhetorical architecture that made Crimea possible is now being constructed around Alberta. That architecture requires foundation stones, and Alberta has them. When the province joined Canada in 1905, Ottawa retained control of Alberta’s natural resources though Ontario and Quebec got to keep theirs. This inequity was corrected in 1930, but the resentment lingered. In 1980, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau imposed a 25% federal tax on Alberta’s oil and seized control of pricing. The backlash was fierce: unemployment soared, projects collapsed, and “let the eastern bastards freeze in the dark” became a rallying cry. Separatist movements have flared and faded for decades, always returning to the same core grievance: Alberta produces 90% of Canada’s oil, Canada sells 95% of it to the United States, yet Alberta feels like a resource colony for Eastern Canada’s benefit.

Russia exploited similar dynamics in Crimea: real economic marginalization, language politics, the feeling of being a colony for Kyiv’s benefit. External powers don’t create these grievances, but they weaponize them. And just as in Crimea, it’s indigenous populations raising the alarm first. The Sturgeon Lake Cree Nation filed a lawsuit arguing that Alberta cannot hold a referendum without indigenous consent, and explicitly warning that a referendum “will enable foreign interference from the most powerful neighbor to the south.” In Crimea, the indigenous Tatar population boycotted the 2014 referendum and suffered systematic repression afterward.

Alberta’s premier, Danielle Smith, has walked a careful line, speaking about her desire to stay a part of Canada while defending the need to hold a referendum. She met Trump at Mar-a-Lago days before his inauguration last year, speaking of the “need to preserve our independence while we grow this critical partnership.” But when the referendum petition was approved, she framed it as a democratic duty: “You need to have a pressure-release valve on issues that people care about.” According to the Globe and Mail, Canadian defense officials have recently modeled a U.S. invasion scenario for the first time in over a century: a theoretical planning exercise, not an operational war plan. The modeling assumed American forces would overcome Canadian positions in as little as 2 days, prompting examination of asymmetric responses: sabotage, drones, dispersed resistance. Officials stressed an invasion remains highly unlikely. But allies don’t conduct theoretical exercises in fratricide unless something fundamental has shifted.

The shifting burden

Stories matter. The current collapse of Europe’s post-Cold War security arrangement began with narratives that made that collapse imaginable.

From the mid-2000s, Russian state television started hosting marginal voices questioning Ukraine’s right to exist. In 2008, the Russian daily Kommersant reported that in a private meeting, Putin told George W. Bush that Ukraine was “not even a state” and that the Kremlin would be encouraging secession in both Crimea and eastern Ukraine. Six years of this rhetoric made Ukrainian sovereignty negotiable before a single soldier crossed the border.

Trump has spent over a year declaring Canada “only works” as part of the United States while his Treasury Secretary publicly advocates for Alberta’s secession and Bannon, whose finger is frequently firmly on MAGA’s pulse, calls the country “hostile” and “the next Ukraine.” Béland warns that the damage from this process extends beyond the referendum’s outcome: “Even if the ‘no’ wins, the remain side wins, and even if it’s an easy victory… having a referendum campaign is highly divisive in and of itself, and it opens the door to potential U.S. interference.”

Sovereignty doesn’t collapse with a single referendum. It erodes in the accumulation of moments when defending it appears unreasonable, when maintaining it requires constant justification, when the burden of proof shifts from those who would divide to those who would preserve.

With additional reporting from Masho Lomashvili