The rumor spread like a storm. One moment it was a whisper in a small Ohio town; the next, it was tearing across newspaper headlines and through talk shows nationwide: Haitians in Springfield were eating cats and dogs.

By the time it reached my inbox, I already knew the lie was out there. What arrived was the first backlash — a venomous email that made clear how deeply the lie had seeped into the American bloodstream. At The Haitian Times, we’ve spent years reporting on Haitians as whole people: musicians, entrepreneurs, artists, families who create, build, celebrate, and endure. We’ve also covered the darker chapters — gang violence, earthquakes, cholera, and migration through unforgiving terrain.

But this lie — this grotesque, calculated fabrication — landed like a punch to the chest. Because it wasn’t just a rumor. It was a diagnosis of how America still sees us.

People imagine exile as geography — leaving one home for another. But exile can also be internal, a quiet ache carried from room to room. Mine began not through my own displacement but by watching my parents live out theirs. Though I’m not technically an exile, I grew up in a household where exile seeped through the walls. My parents were part of the early wave of Haitian migration to New York — educated, middle-class, ambitious. In Haiti they had status. In America they had survival.

50 years on, and belonging still felt conditiona l— granted just until someone decided to snatch it away.

Springfield wasn’t an anomaly. It was a lie engineered to trigger the oldest reflex in this country: the instinct to believe the worst about Black people. Say anything about us — no matter how implausible — and a segment of America will nod along, ready to turn virulent fiction into unimpeachable fact.

In September 2024, during the U.S. presidential campaign, the lie leapt from fringe conspiracy to national talking point. J.D. Vance — then Donald Trump’s running mate — first amplified the claim, asserting that Haitian migrants in Springfield were abducting and eating pets, even after local officials told his staff the allegations were baseless.

Days later, during his first and only debate with Kamala Harris, Trump repeated the claim on national television, declaring that in Springfield, Haitian immigrants were “eating the dogs” and “eating the cats.” On air, the moderator cited the city manager’s office, which said there were no credible reports of pets being harmed by immigrants.

Fact-checkers, including Reuters, also found no evidence. But by then, the damage was done.

Springfield had been on our radar for years. Haitians there had been followed, attacked, and robbed as they carried cash to send home. We’d reported on those incidents, and on how a small Midwestern city struggled to absorb a new Haitian community.

We knew Haitians were no longer settling exclusively in New York or Florida. We were migrating to the Midwest, the Southwest, and the Deep South — regions less accustomed to us and often less welcoming.

At The Haitian Times, we pushed back forcefully against the pet-eating hoax — publishing extensive reporting that debunked it, amplifying local officials’ denials, and demanding accountability. For that, we paid a price. Over the following months, our inboxes and message boards filled with blistering attacks — emails drenched in racism and vitriol, accusing us of lying, covering for “savages,” or participating in imagined conspiracies. The more we insisted on truth, the more determined some were to punish us for it.

We planned two town halls in Springfield — one with local officials, another with the Haitian community. Both were canceled amid bomb threats, rising hostility, and word that white supremacist groups intended to march through the city. Local leaders told us plainly: they could not guarantee our safety.

Then came a phone call I will never forget.

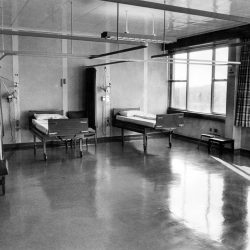

Macollvie Jean-François Neel, our special projects editor, called me early on the Monday after she returned from Springfield. Her voice was taut but steady. She had been doxxed and swatted — targeted by a form of harassment in which someone makes a false emergency report to provoke an armed police response. An anonymous email to Catholic Charities in Rochester, New York, claimed a brutal murder had occurred at her Brooklyn home.

Seven NYPD officers surrounded her house. Guns holstered but ready.

A “wellness check,” they called it.

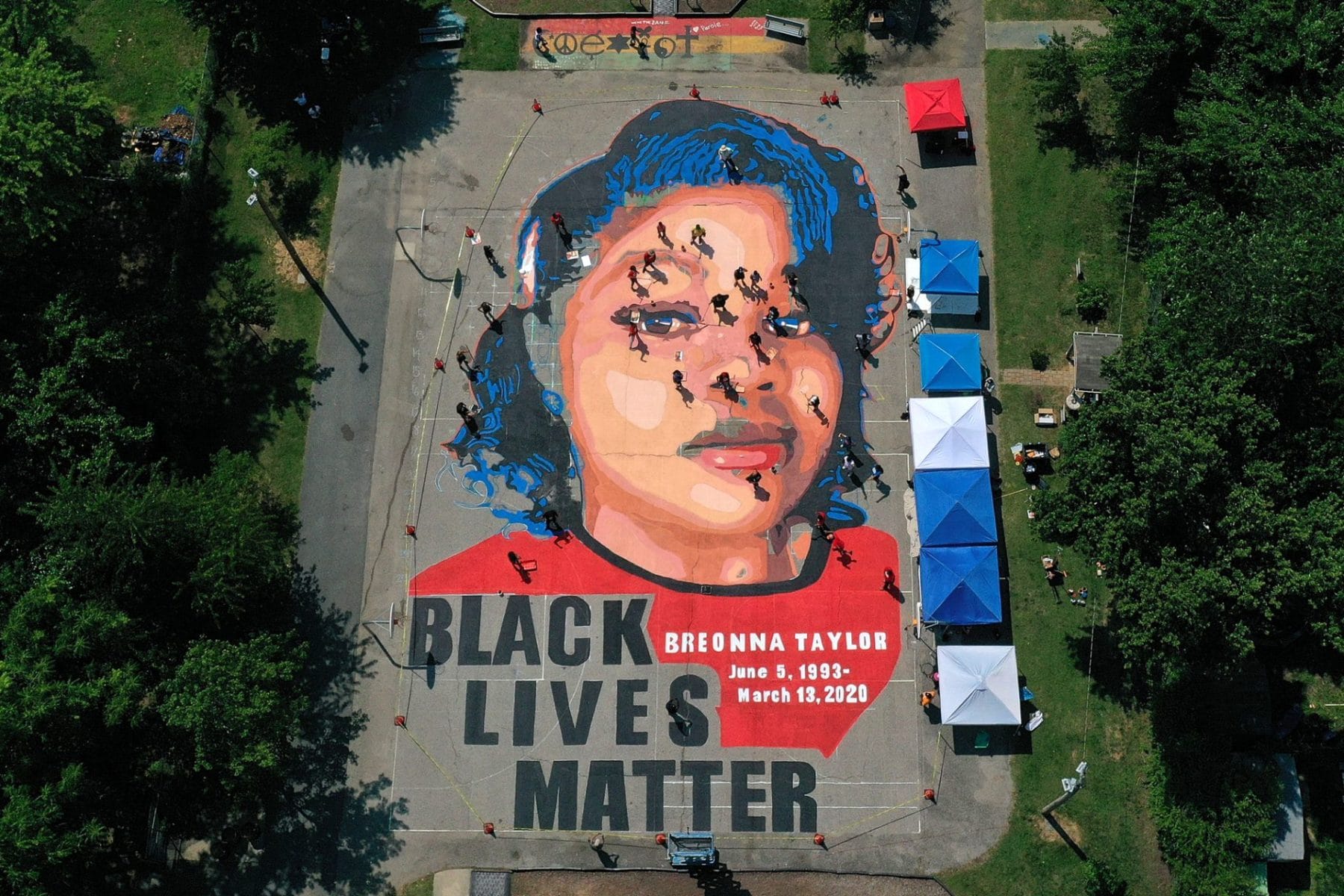

Every Black family in America knows how quickly such encounters can turn deadly. Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old emergency technician in Louisville, Kentucky, was killed in her apartment during a botched late-night police raid. Officers fired more than 30 rounds. She never stood a chance. Atatiana Jefferson, a 28-year-old Black woman in Fort Worth, Texas, was shot through her bedroom window while playing video games with her nephew. Police had arrived for a “welfare check” after a neighbor noticed her door ajar. They never announced themselves. She was killed within seconds.

For many white Europeans, these stories sound unimaginable. For Black Americans, they form a grim, familiar pattern. The dangerous imagination of others is often deadlier than any reality.

After Macollvie finished recounting the incident, I closed my laptop and went on my daily walk, my stride propelled by fury. For nearly an hour I marched through my neighborhood’s nature trail, furious at the fragility of our lives, of the threats to our safety in this country we call our own. Back home, still simmering, I wrote two posts — one on LinkedIn, one on Twitter. They were raw, unfiltered. Within hours, both went viral. Messages poured in. Television bookers reached out. Reporters sought analysis. Allies offered solidarity. Everyone wanted me to turn this wound into words.

And then it clicked: Exile isn’t about a country you leave. It’s about the distance between who you are and who the world insists you must be.

The dual exile

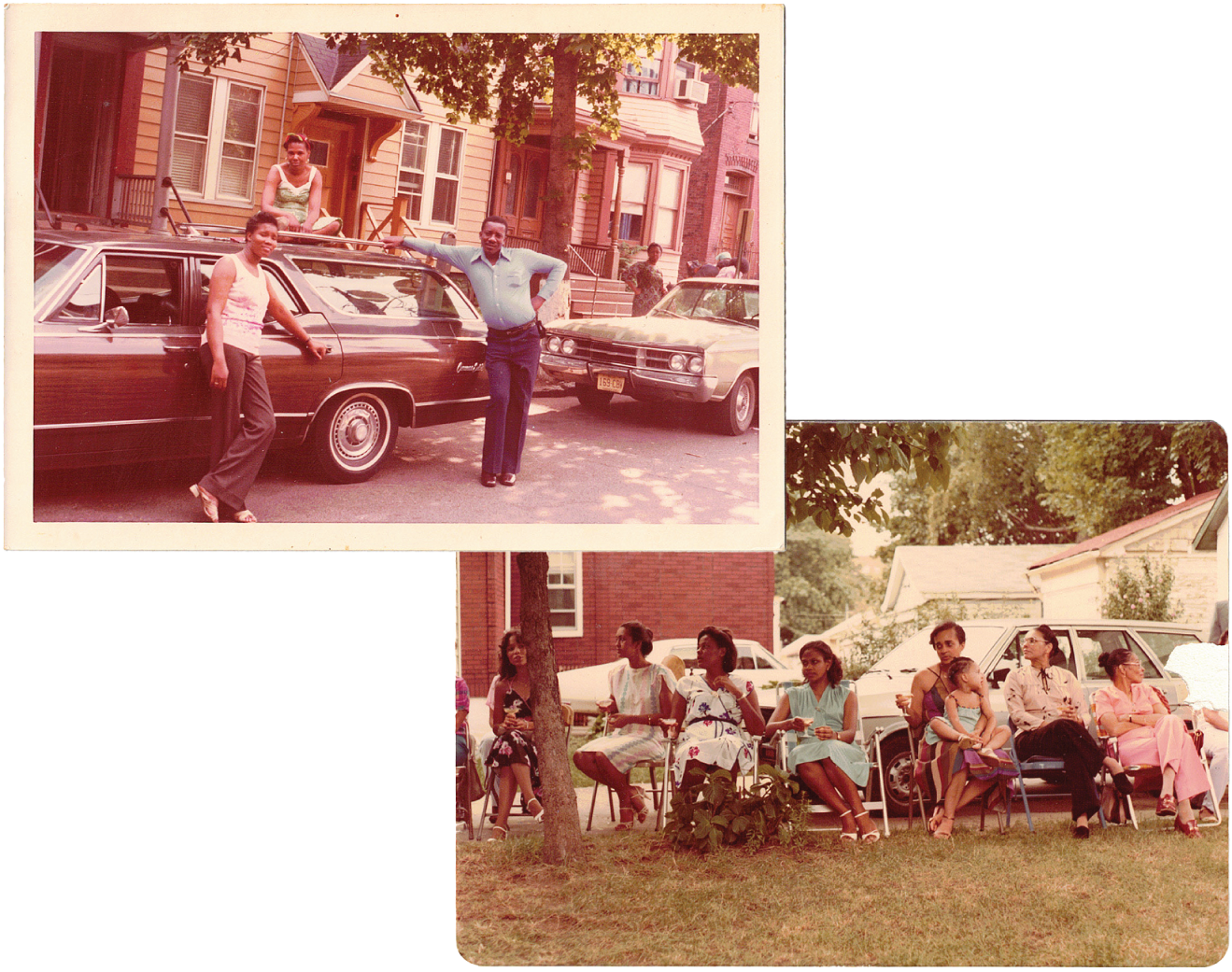

My mother worked in a SoHo garment factory long before the neighborhood became a destination, taken over by galleries and loft apartments. She came home with fingers pricked from sewing needles, the smell of machine oil clinging to her clothes. “School is your salvation,” she’d tell me. “Don’t end up like me.” My stepfather worked as a mechanic at the United Postal Service. My uncles drove taxis, worked factory shifts, held multiple jobs that drained their dignity by the hour. Their friends slid down the American class ladder: teachers became janitors, accountants cleaned office buildings, nurses tended to the elderly in strangers’ homes. Edwidge Danticat once said her Barnard classmates remarked on the irony of our lives in the U.S.: “In Haiti we had maids; here we were the maids.”

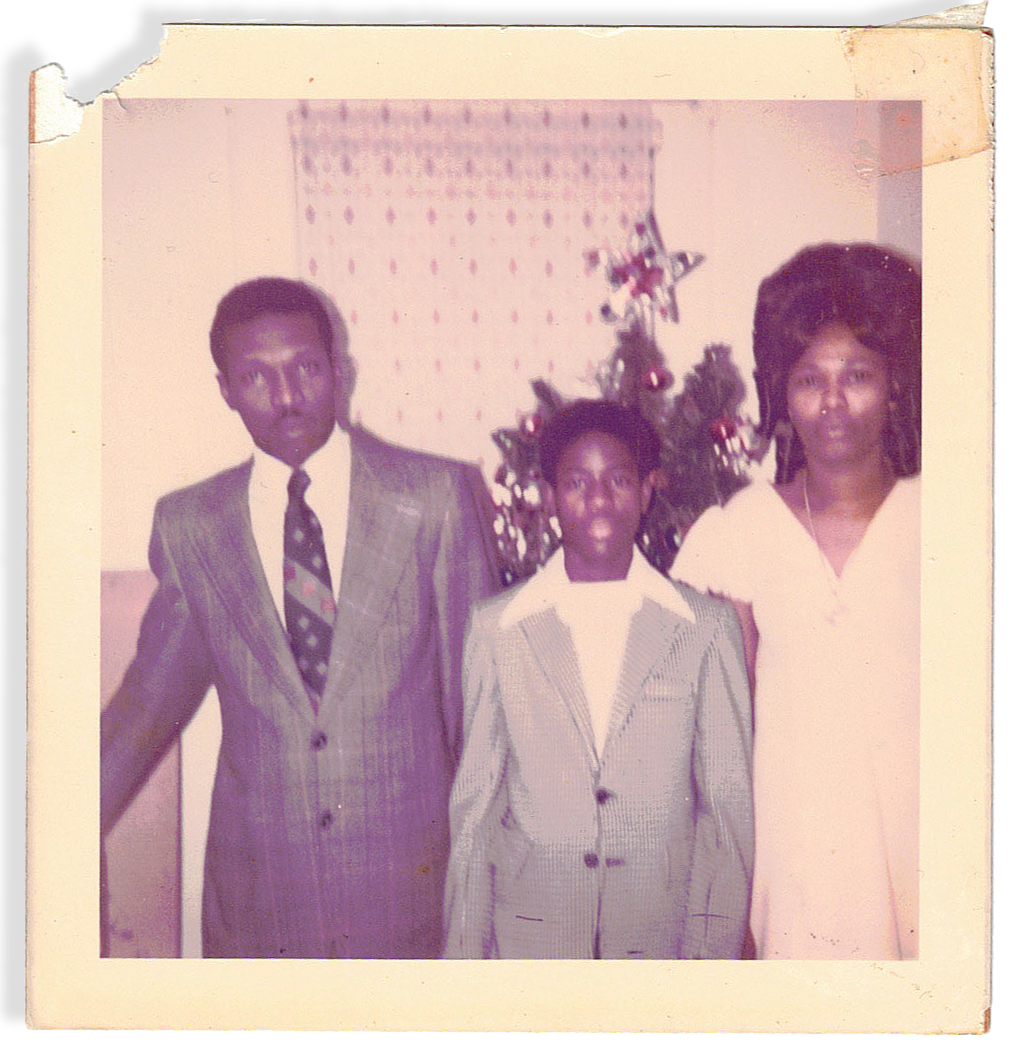

On weekends my parents and their friends gathered in cramped salons across Brooklyn and Queens — passing around rum, grief, gossip. They spoke of a bright, sun-washed Haiti they carried on their person like a pressed flower. They dreamed of returning once the regime fell.

They would turn the music up as loud as the room would allow and sing along to “Haiti”, the iconic ballad by Skah-Shah, then the darling of the Haitian community. I watched their faces as they belted out the lyrics — laughter and grief sharing the same space in their eyes, their voices cracking and rising together.

This morning I woke up with tears in both eyes.

I miss my country. Haiti chérie.

Oh God, give me strength.

My family back home criticizes me when I don’t write letters.

They don’t know my heart is broken.

Life in New York is hard.

As the band slipped into a long, melodic instrumental passage, something shifted. Hips and heads began to sway. Conversation faded. A small living room in Brooklyn filled with movement, with a kind of quiet, shared trance — half celebration, half mourning. This was not simply music; it was a ritual, a way of keeping Haiti alive when distance and circumstance conspired to erase it.

What filled that room was nostalgia — not sentimental, not indulgent, but heavy and necessary. A longing for a homeland that remained painfully present and impossibly distant at the same time. Haiti was close enough to sing to, to dance with, to invoke by name. And yet it was far enough away to break hearts nightly, right there on American couches, under American ceilings.

That was exile, long before I had a word for it.

But the Duvaliers never fell, the regime never changed.

François “Papa Doc” Duvalier ruled through terror. His Tonton Macoutes disappeared intellectuals, tortured dissidents, murdered without hesitation. When he handed power to his nineteen-year-old son, Jean-Claude “Baby Doc,” in 1971, the repression modernized but did not cease.

By the early 1980s — two decades after they had left — my parents acknowledged a truth that crushed them: they would never return home. Haiti had changed. They had changed. Their exile had hardened.

I came of age as part of a bridge generation linking Haiti and America, carrying our parents’ grief in one hand and our futures in the other.

And yet, there were moments of joy — brief flickers where we felt we belonged in America. In elementary school, making the basketball team thrilled me. In high school, soccer became a sanctuary. Team sports offered respite from isolation, a glimpse of camaraderie, a doorway into American culture. For a while, I thought that was what belonging meant, what it felt like — this rush, this folding into something larger.

Summer league team Sunshine Football Club, Elizabeth, NJ

The closest I ever came to that sensation of belonging was in college, at Florida A&M University in Tallahassee. The historically Black university sits atop one of the city’s seven hills, and when I arrived it felt less like a campus than a citadel — an elevated space of Black thought, ambition, and self-possession. Almost immediately, I felt the intellectual electricity that coursed through the student body. Most students came from Florida, but many arrived from the Midwest and the Northeast, carrying with them different accents, histories, and shades of Blackness.

I sought out FAMU deliberately. Growing up in Elizabeth, New Jersey, tensions between Haitians and African Americans simmered constantly. There was suspicion on both sides. We didn’t understand one another. We didn’t speak the same way. We didn’t trust one another. I remember telling my mother, shortly after arriving in New York, that I was surprised by how many Haitians there were. She laughed and said there weren’t — that I was mistaking Black Americans for Haitians. That confusion captured something essential: in America, Blackness is often flattened, stripped of its histories and distinctions.

FAMU took what was flattened and gave it shape. It was a place where learning how to navigate white power in America was not incidental but central to the institution’s mission. Late at night, between studying and watching Black Entertainment Television, we debated politics, culture, and survival — how we would confront the world waiting beyond campus. That search for connection carried me to West Africa as a Peace Corps volunteer in Benin and Togo, where I deepened my Pan-African quest to understand the relationship between continental Africans and the diaspora.

Still, even in that Black oasis, belonging proved brittle. The mother of a woman I was dating despised me. One day, she looked me in the eyes and said, flatly, that Haitians ate cats. It was a chilling reminder that even among our own, exile stuck to us, a second skin.

It was with this inheritance — the contradictions, aspirations, flashes of connection — that I founded The Haitian Times in 1999. Not just as a newspaper, but as a repository for our stories, where they could be kept without distortion. It was a ledger of our collective presence. A home for a scattered people. Over 25 years, the paper has chronicled immigration battles, homeownership milestones, the rise of Haitian nurses in American healthcare, the emergence of entrepreneurs, artists, and scholars reshaping Haitian American identity. We became a mirror — and often a megaphone — reflecting a community still discovering how to belong.

But journalism, too, would show me my place.

When I joined The New York Times, I was welcomed but not fully claimed. Editors called one of my beats “immigration.” I called it covering immigrants — the lifeblood of New York’s buses, subways, corner stores, and neighborhoods. I wrote about cab drivers navigating midnight streets, nannies raising other people’s children, shopkeepers who kept entire blocks alive. Immigrants animated the city; I simply made them visible.

Yet I always operated with one hand on the door. The profession embraced me, but not always my perspective. The city was my subject, but rarely my home.

Running The Haitian Times deepened this duality. By day, I covered life in America; by night, I remained tethered to Haiti’s turmoil and beauty.

Two places claimed me. Neither fully let me in. That was the essence of my dual exile: belonging everywhere and nowhere at once.

Family gathering in Jamaica, Queens

The rotating outsider

After 50 years in America, I’ve learned that each generation selects its “other”: Italians; Jews; Irish; Chinese; Indians. Each group, at different moments, was caricatured and feared. Over time — through numbers, proximity, and the strange elasticity of whiteness — they moved inside the circle.

I’ve seen this happen among South Asians. Some came with little money, scraping by as taxi drivers, convenience store owners, warehouse workers. Their stories echo the struggles of the countless immigrants navigating America’s lower rungs. But others arrived with advanced degrees, English fluency, caste and class privilege, and global networks. Many entered the American middle and upper-middle class swiftly, achieving what sociologists call adjacency — not whiteness, but a comfortable (and falsely comforting) proximity to power.

When Zohran Mamdani, an Indian-Ugandan-American of considerable social and cultural privilege, became the city’s first Muslim and first South Asian mayor, his victory — powered by a multiracial, multi-class coalition — showed how adjacency can become influence, and how an immigrant-led movement can capture the helm of America’s largest city.

But Haitians do not enjoy adjacency.

We arrived at the intersection of Blackness and foreignness — the two most enduring definitions of “other” in American life. We did not come through elite work visas or tech pipelines. We fled dictatorships, poverty, violence. We arrived with determination but often without capital, language, or protection. And in America, race does not rotate like ethnicity does.

A white ethnic group can become white-er.

A Black immigrant group can only become Black-er.

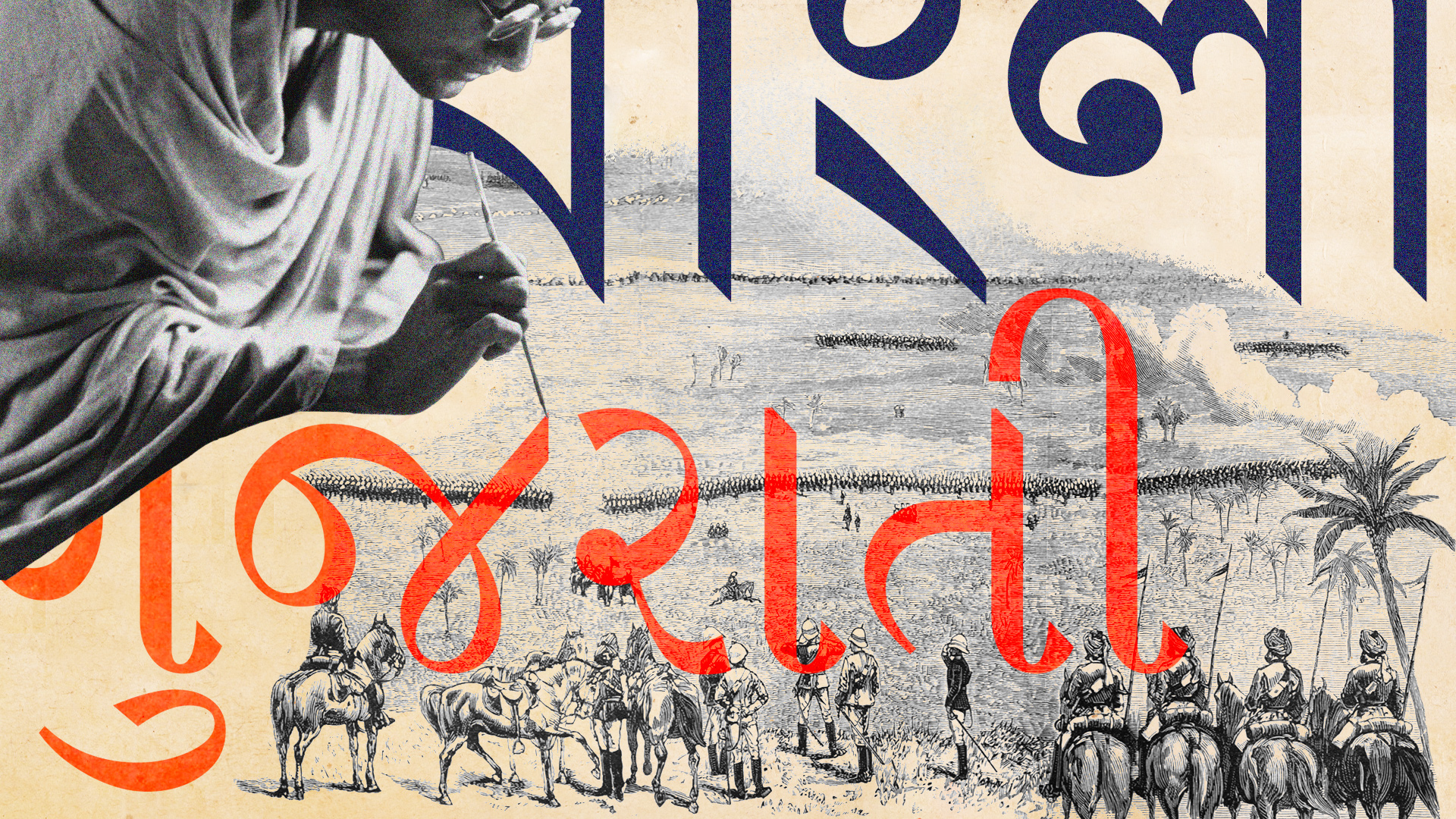

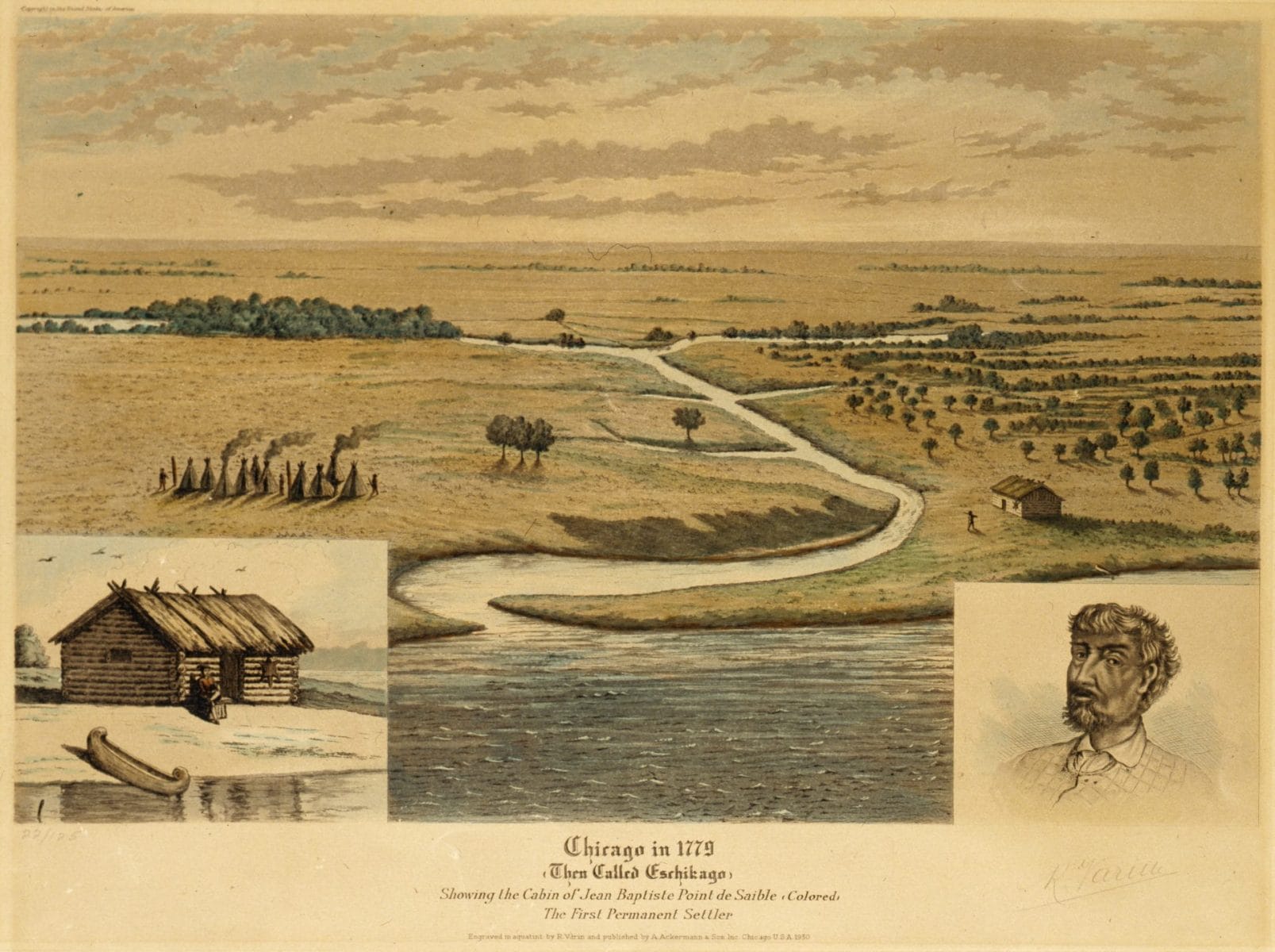

This is why the Springfield lie metastasized so quickly and so easily. Why strangers felt entitled to weaponize their fear against my colleague. And yet the irony is astonishing. Haitians are cast as permanent outsiders in a country we helped shape from its earliest days. It was a Haitian, Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, who founded the city of Chicago. Haitian refugees fleeing the revolution ignited cultural, political, and demographic transformation in New Orleans. In 1779, more than 500 free Black soldiers from Saint-Domingue, the Chasseurs-Volontaires, fought alongside American revolutionaries in the Battle of Savannah. They bled for a nation that today treats their descendants as intruders.

The outsider label is not simply a misunderstanding. It is deliberate erasure.

Always on the outside

Bob Dylan — my favorite poet of contradiction — wrote a line that has lived with me for decades:

“Always on the outside of whatever side there was.”

The moment I heard it, I recognized myself. It linked me to a lineage of Black artists and intellectuals for whom exile became a survival strategy: Richard Wright. James Baldwin. Chester Himes. Nina Simone. They left because America made it too hard to breathe, too hard to think, too hard to exist with dignity.

Baldwin said leaving America saved his life. In Paris he found the distance he needed to see his country clearly — and to write about it with a heat that still sears.

Sometimes I wonder what might have happened had I chosen their path.

But I stayed, remaining in the place that wounded me even as I strove to be the change that I wanted to see in America. Journalism allowed me to confront exile directly, to define myself before others misdefined me or my community. It gave me a language for the fracture I had always felt both within and without.

There is a line often attributed to Baldwin — not literal, but true to his philosophy: The place in which I’ll fit will not exist until I make it.

So, I made something. A newsroom. A community institution. A bridge for the bridge generation.

But creation did not erase exile. It only gave it form — Springfield, Macollvie’s swatting, my parents’ sacrifices, the precariousness shadowing every Black immigrant life. These moments showed me that America will welcome our labor, our tragedies, our “resilience” — but still choose not to welcome us. I am not on the outside because I failed to belong. I am on the outside because America’s borders of belonging were never drawn with people like me in mind.

Duvalier, Jean Claude ‘Baby Doc’ (center) surrounded by military personnel 1972, Haiti.

Haitians march past the gleaming white National Palace after “Papa Doc” took over the Presidency for Life, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 1964. Bettmann / Contributor.

Claiming belonging

After Springfield, after Macollvie’s ordeal, after months of racist email invective and those two viral posts, I realized something else: Belonging in America is not given, is not granted. It is claimed. It is not secured by citizenship, longevity, or contribution. It is forged through community, through institutions, through memory.

But even those who would claim belonging, now face the anger and aggression of those who would deny it to them. In recent years, The United States has witnessed:

- ICE raids tearing families, schools and cities apart

- Asylum seekers detained in maximum security prisons

- The Muslim ban, the casual abuse directed at those from “shithole” countries

- Family separations at the southern border

- The normalization of open xenophobia

- The resurgence of white supremacist violence

Under the Trump presidency, these are not expressions of our worst selves. They are public policy. They reveal a nation increasingly comfortable with cruelty, increasingly hostile to outsiders, increasingly eager to weaponize belonging. And now the question is: What will post-Trump America look like?

Even when the man exits the stage, the movement he unleashed will outlive him. Suspicion once fringe is now mainstream. Scapegoating once coded is now explicit. Viewing neighbors as threats is common currency.

These currents are not confined to the United States. Across Europe — from France to the U.K., Italy to Hungary — immigration has become a proxy for deeper anxieties about culture, identity, and power. Borders harden. Parties shift rightward. The definition of “belonging” becomes forbiddingly narrow.

For immigrants — especially Black immigrants — this means we must build parallel structures of safety, connection, and truth. We cannot rely on our nations to protect us. We must protect ourselves.

In recent months, I’ve found myself returning to what happened in Springfield in August and September 2024, and to the question that kept rising in the quiet afterwards: How did we find the will to continue to report, to insist on telling our truth even when fear crept inside our own newsroom, to insist that we had a right to be here, to be seen and to be heard?

For me, the answer arrived slowly, like a figure emerging through fog. There are forces in this country — loud, coordinated, and intentional — that want people like us to feel like exiles. They want us to retreat into silence, to internalize the idea that we are perpetual outsiders whose presence can be erased with a rumor, a smear, a threat.

My parents and their peers had lived under Duvalier’s dictatorship, where fear was a currency and silence a survival tactic. They fled a regime that demanded their obedience through terror. But in these United States, I refused to reenact their posture of cowering and running.

America likes to imagine itself as a shining city on a hill — a beacon, a north star. But Springfield revealed an America where the light feels less like a guiding glow and more like a rotating lighthouse beam: illuminating some, ignoring others, blinding many.

After 50 years, I have learned this: Exile describes where others place you. Belonging is what you build with your own hands.

So I stand my ground. Not because I believe in the myth of the hill, but because I believe — fiercely — in our right to stand upon it.

Even if America insists on keeping me just outside the circle, I will stand outside it and keep writing. From this vantage, I can see my country clearly enough to tell the truth about it. And I can see Haiti clearly enough to honor it. I can see my parents clearly enough to understand their sacrifices. And I can see the next generation: those Haitian American children who will read our stories and recognize themselves within them.

That — more than safety, more than acceptance, more than any passport — is belonging.