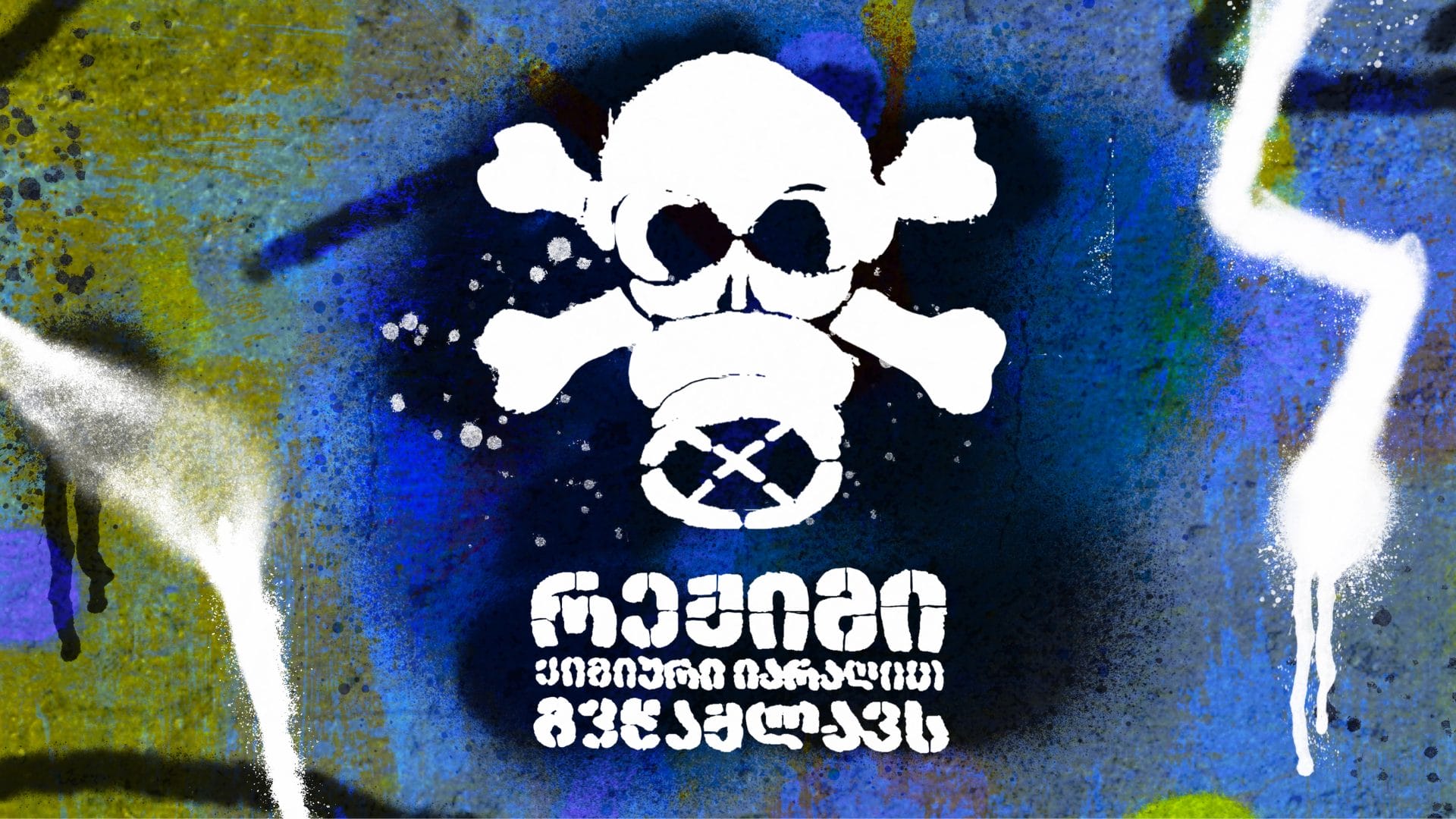

On December 1, I, and thousands of my fellow Georgians, found out we might have been poisoned by our own government. The toxin was likely a chemical introduced in World War I and supposedly phased out by the 1930s: ‘bromobenzyl cyanide’, also known as ‘camite’.

We learned this from a BBC documentary. The government didn’t admit any wrongdoing, let alone apologize. It didn’t even launch a credible investigation. Instead, it followed a playbook now familiar across the world’s democracies-in-decline: deny everything, attack the messenger, and punish the truth-tellers. Within days, Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze threatened to sue the BBC — citing Donald Trump’s recent lawsuit as precedent and calling the documentary “a cheap provocation orchestrated by foreign intelligence services.”

The State Security Service summoned Georgian doctors, protesters, and NGO workers who had spoken to the BBC, interrogating them under procedures typically reserved for serious crimes. The charge: assisting a foreign organization in activities harmful to Georgia’s “national interests.” This kind of aggressive denial isn’t unique to Georgia. In 2023, for instance, the Indian government banned a two-part BBC documentary which explored the rise of Narendra Modi, including accusations that when he was chief minister of Gujarat, he enabled the slaughter of hundreds of Muslims in statewide riots. The Indian government described the documentary, in language strikingly similar to that used by the Georgian government, as “a propaganda piece designed to push a particular discredited narrative.” Just last month, the White House said the BBC was a “leftist propaganda machine.”

But the inconvenient truth is that I was there when the Georgian government sprayed us with chemicals. And I know how it felt.

Let’s rewind. Over a year ago, in November 2024, when the Georgian government announced that it was halting the constitutionally-promised integration process with the European Union, hundreds of thousands Georgians spontaneously flooded the main avenue in the capital Tbilisi. The government’s announcement had taken the protesters by surprise. But, in turn, the ruling party, the Georgian Dream, clearly did not anticipate the size of the protests or the mood of the protesters.

I had left my house expecting another midsize protest. For a month, Georgians had been protesting against an election that had brought Georgian Dream back to power and that the country’s president at the time, Salomé Zourabichvili, said was a “Russian special operation.” I got there early and the crowd was nowhere near its peak, but as soon as I arrived, I knew this was something different. There were no speakers on platforms, no pre-planned messages brandished on placards. Instead, thousands of people stood together, some banging on metal barricades around the parliament building, and chanted ‘revolution’. You could feel the anger and frustration in the atmosphere.

I called a friend at the Ministry of Internal Affairs. “They are mobilizing all of us,” he warned me. “Even from other cities. Everyone’s been told it’s a red alert.”

What followed was a long, relentless night.

Crowd control quickly became punishment — an endless rain of teargas, watercanon and pepper spray, a storm of police beatings and fractured bones. On the first night of the protests alone, 207 people were taken to hospitals around the city. The protesters, most of whom had no protection, would scatter but gather again. Over and over for more than a week.

My friends, acquaintances, and protesters I have interviewed, often recall these days as a fever dream. Almost all of them have a dramatic story of what it felt like to be on the receiving end of the government crackdown. It was, agrees everyone, unprecedented. See, Georgians are no strangers to protests and neither to government crackdowns. But this time, everything was on steroids. Beatings by the Special Forces were savage and aided by uniformless, government-hired thugs. Rustaveli Avenue, the main drag, was covered in a thick fog of tear gas, the water canons seemed to have an endless supply of liquid that burned your skin as soon as it made contact with it. The smell of chemicals lingered in the air.

Protesters who managed to avoid being physically beaten, but couldn’t avoid the teargas and other measures, talked about experiencing violent coughing fits, spells of lightheadedness and nausea. In more severe cases, protesters passed out, vomited, had nose bleeds and a persistent skin irritation. Many people described these symptoms on social media, even as they kept going out each night to protest. “We were soaked, it was freezing, and I couldn’t breathe,” Tata Khundadze told me about being hit by sprays from the police water cannons. “My skin felt like it was on fire. It became too much — I lost consciousness.”

In the days that followed, Khundadze shared photographs online that showed a severe red rash on her hands and face. She developed open wounds on her skin that began to bleed. For several weeks after the incident, she continued to vomit, sometimes throwing up traces of blood. She thought maybe her capillaries had burst. “But in reality,” she says now, “who knows what happened, what we inhaled, what went into our lungs and what did not.”

Many protesters, including Khundadze, speculated that the government was using an unknown teargas spray. Local news outlets started asking questions. Doctors called on the government to ease the measures, some even signed a petition demanding the disclosure of the chemicals used during the crackdown. The government denied any wrongdoing. But public speculation continued. More people spoke about suffering prolonged effects, but without access to police records or chemical analyses, their suspicions remained unprovable.

The story stalled.

Then, this month BBC Eye released its hour-long documentary. After harrowing accounts from protesters about police brutality, the documentary turns its attention to what was in those water cannons. We hear from protesters, activists, lawyers and doctors who tried to sound the alarm. The viewer is introduced to Dr. Konstantine Chakhunashvili who, along with his brother, surveyed nearly 350 affected protesters. “Last year, on the 11th of December, after I left administrative detention, I found out that many of my friends were still experiencing nose bleeds,” he told me. “I wondered why.” Konstantine and his brother’s study found several irregularities compared to the effects of conventional riot control agents. But they couldn’t pinpoint what caused the irregularities.

The documentary-makers spoke to Lasha Shergelashvili, the former head of weaponry for Georgia’s riot police. Shergelashvili, who left the ministry in protest after the brutal crackdowns, claimed that he tested a mysterious compound in 2009, before Georgian Dream came to power three years later. He described its effects as “probably 10 times” stronger than regular teargas and recommended against its use. Anonymous current officers confirmed that the same compound Shergelashvili tested in 2009 was used during the 2024 crackdown.

And then a key document surfaced. The BBC obtained a copy of the inventory of the Special Tasks Department, from 2019, listing two unnamed substances: “Chemical liquid UN1710” and “Chemical powder UN3439,” with instructions for mixing them. UN1710 is identified as a solvent. UN3439 takes longer. It’s a hazmat classification, not a chemical name. Experts are consulted, options eliminated. Eventually, only one substance fits the description: bromobenzyl cyanide — a WWI–era chemical agent.

While watching the documentary, I felt a strange mixture of emotions. I was angry but not in any way shocked or surprised. We discussed the documentary among friends and family, agreeing how disturbing the whole thing was. Then, in true Georgian spirit, we made jokes about it.

Tellingly, though, no one around me, including supporters of Georgian Dream, questioned whether the ruling party was capable of such evil.

The government’s response was fast and furious. Officials and government-affiliated media dismissed the documentary as fake news spread by some shadowy global “deep state.” But their denials were inconsistent. The current minister of internal affairs denied the existence of ‘camite’ in their arsenal. But the minister at the time of the protests admitted that the government had had access to camite since 2009, though it did not use it. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Kobakhidze confirmed that there was indeed something in the water but refused to share what it was, before calling on the UK government to apologize on behalf of the BBC.

The Georgian government did launch an investigation into the “abuse of official authority.” It took barely a week for the investigation to conclude that the water was laced with a standard teargas agent. Even discounting the speed, the investigation was farcical — why did the government need an investigation to “find out” what chemicals it was spraying on protesters?

Meanwhile, a separate investigation was initiated into the people who had taken part in the BBC documentary. Konstantine Chakhunashvili, the doctor, was one of the main targets. Government spin doctors said the BBC’s conclusions around the use of camite rested entirely on his findings and were therefore not valid. But Chakhunashvili’s study never attempted to narrow down which chemicals caused the effects he had observed. With the government’s insistence that the documentary is the product of a foreign plot, it will likely be used to further limit the access of foreign journalists to Georgia, while tightening domestic media laws. And Chakhunashvili fears that academia won’t go unpunished either.

For me, the main thing the documentary gave me was some validation. As a journalist, I spent every day of the protests standing right on the dividing line between protesters and special forces. I inhaled absolutely every single chemical released onto Rustaveli Avenue that week and was directly hit by the spray from water cannons twice. On one of those nights, when I got back home at seven in the morning, my whole body was burning. I stood in the shower for an hour pouring water, a saline solution and even milk over myself, only to go to bed with my \ body still on fire. I coughed for months onward and still, a year later, I don’t feel like my breathing is back to normal. But now I know, I am just one of the people who suffered prolonged and mysterious after-effects, many of whom are now dealing with much more serious lung and heart ailments.

Two weeks after the revelations, it’s clear — whether specifically camite or some other hazardous compound — chemicals were used that caused injuries far beyond approved riot-control standards. Our speculations have been justified. Yet, with little hope for a proper international investigation, we are left in limbo, still wondering if the symptoms we felt were caused by sheer exhaustion and overwhelming amounts of gas and pepper spray, or if indeed, a World War 1-era chemical is, or was at some point, inside our bodies.

For people whose lives and health have been drastically altered by the events, it means that they will have to continue spending endless days and money, looking for medical answers on their own.

I am still unsure whether Georgian Dream understood exactly what they were doing. I think they were aware of at least the immediate effects of the mixture, but I cannot be certain that they fully planned to poison protesters with a chemical weapon. When a government is driven solely by its desire to hold onto power, its judgement becomes clouded. When you see fellow citizens with different, opposing views as enemies, limits dissolve. When there is no check on your actions and your power, you take reckless decisions. And one day, when you endanger the lives of your compatriots, your lucky streak, your immunity, might run out.