In June 2019, I stood in the corner of a hotel ballroom in Athens and watched as some of the most prominent publishers and senior editors from across the European continent were made to sit blindfolded on chairs arranged in circles.

It was past midnight. The bar had been open for hours. In this dimly lit space, Google executives moved between the circles, their voices cutting through the nervous laughter.

“Werewolves, wake up,” one of them commanded. “Choose your victim.” The blindfolded editors, people who ran newsrooms, who held governments accountable, who prided themselves on their clear-eyed analyses of current affairs, tilted their heads toward the voices of their hosts, trying to decode who among them was predator and who was prey.

This was the climax of NewsGeist, Google’s annual gathering for publishers and editors. The game was Werewolf, sometimes called Mafia, a contest of deception and power where “villagers” must identify the killers among them as they are being eliminated one by one. Google executives, led by Richard Gingras, the company’s Global Vice President for News, acted as game masters. They decided who could speak, who had to stay silent, who lived, and who died. The editors participated enthusiastically. Some had flown in on Google’s dime. Many had received grants from the Google News Initiative, the company’s billion-dollar program to support journalism innovation. All of them depended on Google’s algorithms to surface their journalism to readers.

I played one round, but felt so uncomfortable I decided to watch from the edge of the room, struck by how the whole scene looked like performance art: a dramatization of the actual relationship playing out in the real world beyond this ballroom. Publishers were going broke trying to survive in an ecosystem Google had architected. Google decided what lived and what died in its search rankings, in ad auctions, in the fundamental infrastructure of digital publishing. The parallels seemed too obvious to miss. But in Athens, everyone was laughing, playing along, bonding over cocktails and clever game theory.

Six years later, in October 2025, I finally got to ask Richard Gingras if it had occurred to him that Google executives commanding blindfolded editors in a game of power and deception might be a metaphor for the actual relationship between Google and journalism.

He looked genuinely surprised.

“No, it didn’t,” he said. “Oh gosh. Oh my gosh. No!”

The question no one asked

When the International Press Institute asked me if I wanted to interview Gingras on stage at their annual congress in Vienna, my first instinct was to say no. I knew it would likely be a futile exercise: a single interview against his substantial public platform. Although now retired from Google, Richard Gingras remains a towering figure in journalism circles, a 73-year-old who had spent five decades at the intersection of media and technology, including nearly fifteen years as Google’s senior voice on journalism matters. Throughout that time, he’d been a fixture at every major industry conference, built personal friendships with leading editors across the world, and positioned himself as journalism’s thoughtful critic and advocate.

But I said yes because despite being perhaps the most influential voice in shaping the relationship between the world’s most powerful information company and the journalism industry, Gingras had never been asked to account for what he had built. And as journalism now lurches into a new era of AI dependency, making the same mistakes with companies like Microsoft that it made with Google, I wanted to know: Could one of the architects of the first wave of platform capture reflect honestly on what he’d created? And could that self-reflection help us to avoid repeating the pattern?

The lesson from a Central Asian autocracy

The morning of the interview, I woke with a knot in my stomach that sent me straight back to another interview, nearly twenty years earlier. I was 26, newly appointed as the BBC’s Central Asia correspondent, and I’d secured an exclusive with Nursultan Nazarbayev, Kazakhstan’s president who hadn’t spoken to any foreign media in fifteen years. A friend had arranged it on one condition: I couldn’t ask about the corruption charges against Nazarbayev in the United States. On the morning of the interview, my friend called to remind me his career would be on the line if I broke that promise. I felt physically ill walking into that room, not afraid of Nazarbayev, but sick at the thought of betraying someone who’d helped me and who would pay the price for my question.

I asked anyway. Nazarbayev was furious. My friend didn’t speak to me for months. But I learned something that has shaped every difficult interview since: Power protects itself not through crude censorship, but through relationships, by making you feel that asking the question would be a betrayal of someone who trusted you, who opened doors for you, and who would now suffer consequences.

Comparing a Central Asian dictator to a former Silicon Valley executive may seem absurd. Richard Gingras is no authoritarian. He doesn’t imprison dissidents or threaten reporters. He hosts conferences, funds initiatives, and builds relationships. But the mechanism is identical. In Vienna, the discomfort I felt wasn’t about betraying a friend who had helped me, it was about breaking an unspoken professional consensus. Gingras had made himself indispensable to journalism, not through threats but through generosity, access, and genuine engagement. Asking hard questions of someone who has positioned himself as journalism’s ally, who many of my colleagues consider a friend, who has funded their projects and attended their events—that feels like betrayal not because he’ll retaliate, but because the entire system is built on not asking the question.

Architecture of Capture

Journalism that protects relationships isn’t journalism at all. Yet that’s precisely what journalism did with major platforms, especially Google. For fifteen years. Gingras was at the center of a carefully constructed ecosystem of dependency. Publishers couldn’t survive without Google’s traffic. Google didn’t need publishers — but keeping them dependent, grateful, attending conferences, accepting grants, led to them obliging their benefactors by being effectively blind to what was happening to their industry, what was being done to it.

Journalism was seen as politically important by Google leadership way out of proportion to its revenue-generating potential, because of its influence on public perception and potential regulation. The same was true at Meta. News executives inside these tech companies had big titles, meaningful infrastructure, and significant access to top leadership, but that access came with an implicit understanding about what questions wouldn’t be asked. Publishers didn’t want to be left behind but, unknowingly, they were sealing their fate.

This power dynamic extends far beyond one company’s relationship with one industry. At Coda Story, where we’ve spent years investigating how authoritarian regimes capture institutions and reshape information systems, we recognize the pattern. The same architecture of dependency that Google built with journalism is now embedded across every sector where technology companies control infrastructure. These companies are largely opaque and unregulated, yet they control the essential infrastructure of modern life. App developers depend on platform stores. Startups depend on cloud providers. Musicians depend on Spotify for discovery and revenue. Artists depend on Instagram for visibility. Schools depend on Google Classroom and Chromebooks. Media organizations now depend on AI companies whose models train on their content and are increasingly embedded in workflows, suggesting headlines, making edits, writing summaries. The negotiations happening today mirror what happened with Google and journalism fifteen years ago.

Understanding how journalism was captured matters especially because journalism was meant to be the institution that held power accountable. When journalism itself becomes dependent on the platforms it should scrutinize, unable to ask hard questions without risking its survival, the entire accountability infrastructure collapses. Tech platforms control the infrastructure upon which democratic institutions operate, and those institutions have learned not to examine that control too closely. What happened with Google and journalism is now the template. This is why reflecting on what Gingras built matters: not to relitigate the past, but because the pattern is repeating itself. If someone as thoughtful and engaged as Gingras can’t examine what happened during his tenure, what hope do we have for accountability as these dependencies deepen?

The test

In preparing for our conversation, I read everything Gingras had published recently. He is incredibly eloquent, and I found myself agreeing with much of what he wrote: his observations about echo chambers, about oversimplification, about journalism’s failures. In much of his writing, he invokes his father-in-law Dalton Trumbo — the screenwriter who chose prison over compliance with McCarthyism — as evidence of his own intimate understanding of authoritarianism. He writes eloquently about polarization and journalism’s narrow focus on accountability reporting.

Intellectually, I find much of Gingras’s critique of journalism provocative and not entirely without merit. But it also felt self-serving. Take his recent piece about what he calls “the Woodward-Bernstein effect,” in which he argues that journalism’s post-Watergate focus on accountability reporting has become “problematic,” that it’s turned journalists into “the town scold” and “arrogant know-it-alls.” Our team at Coda has spent years covering technology companies, and Google was consistently the most opaque, the most difficult to get answers from—genuinely harder to hold accountable than the fossil fuel companies I’d covered in the past. For fifteen years, Gingras was the friendly face of that opacity. And yet, he writes thousands of words diagnosing journalism’s problems while writing almost nothing about Google’s role in creating them.

I wanted to know: Could he apply the same analytical rigor to Google that he applies to journalism?

Here are the highlights and then the full transcript of the conversation that unfolded.

Key moments from the interview

- On power asymmetry: When asked if Google had power over journalism, Gingras initially deflects, then eventually says “You want me to say yes? Yes. I don’t understand the point.”

- On the Trump inauguration: Gingras says “the White House was very clever in staging that situation” to create the photo of tech executives at Trump’s inauguration,” and insists “that’s the last photo Sundar ever wanted taken. We don’t support this administration.”

- On the Navalny app: When confronted about Google removing Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s voting app at Putin’s demand — after invoking his father-in-law Dalton Trumbo who chose prison over compliance — Gingras says he “wasn’t involved in that specific decision.”

- On Google’s impact: Gingras repeatedly denies that Google disrupted journalism’s revenue model or harmed the industry.

- On accountability: When pressed about why he writes extensively criticizing journalism but not Google, Gingras says the questions raised are about decisions he “wasn’t involved with.”

- On dependency: When told publishers’ relationship to Google is like “controlling the oxygen,” Gingras responds: “What do you mean control the oxygen? Why don’t you just explain it to me instead of talking in metaphors?”

- The audience intervention: An audience member cites DOJ monopoly findings and ongoing lawsuits, providing legal specificity about Google’s market dominance that Gingras cannot dismiss as opinion.

- On News Geist and CNTI: Gingras reveals that News Geist, Google’s annual conference for publishers, has been moved to CNTI (Center for News, Technology & Innovation), an organization he co-founded with Marty Baron, Paula Miraglia, and Maria Ressa. Google remains a sponsor.

- The Werewolf moment: When asked if he’d ever considered that Google executives commanding blindfolded editors in a game at News Geist might be a metaphor for the actual relationship, Gingras responds: “Oh gosh. Oh my gosh. No.”

Editor’s note: Throughout this conversation, Gingras used “we” to refer to both the journalism industry and Google. At the end of the interview, he clarified: “I’m here representing my own views” and emphasized he was speaking for himself, not on behalf of Google. We contacted Google for comment on what was said in this conversation but at the time of publication had yet to hear back. We will update if we do. Gingras now chairs Village Media and is on the board of CNTI (Center for News, Technology & Innovation) with journalists including Marty Baron, Paula Miraglia, and Maria Ressa. The transcript of the full conversation below has been lightly edited for clarity.

The Transcript

Natalia Antelava: Just slightly reframing the introduction (to this session): This is framed as a conversation on the program, but really, for me, it’s an opportunity to ask Richard some questions that I’ve always wanted to ask.

My name is Natalia Antelava. I am co-founder and editor-in-chief of Coda Story, and throughout my career, first as a BBC correspondent covering conflict zones and authoritarian regimes, and then as editor-in-chief of Coda Story, I’ve watched how information systems shape power, how companies make choices when authoritarians demand compliance, and how journalism’s business models have collapsed. I don’t think anyone has more to say about all of it than Richard Gingras, who spent 15 years at Google. I’m grateful to IPI for giving me this opportunity, and grateful to you, Richard, for sitting down.

So the first question I want to ask you is actually about pronouns. I’ve noticed in the pieces you sent me — and I know you’re no longer at Google, but even before you left — you often refer to media and journalism as “we.” Can you explain that “we”?

Richard Gingras: Media and journalism, oh, you mean including me? Yes, most certainly. Well, first of all, I spent five decades of my career at the intersection of media and technology and public policy, mostly in media. I started out in public broadcasting in the United States during Watergate. So it was a pretty seminal experience. In fact, by the way, my mentor back then said something to me that influenced my career — this was 1974. He said: “Richard, if you’re interested in the future of media, stay close to the technology, because it establishes the ground rules and the playing field upon which it’s played.” And that certainly has influenced my career, but I feel I’ve always been part of the media.

Natalia Antelava: Including when you were at Google?

Richard Gingras: Including my work at Google. You know, it was obviously very much embedded in what we could do as a tech company to help enable and grow not only the media ecosystem, the journalistic ecosystem, but how we could connect our users to important, relevant, and authoritative sources of information. So to me it was very much about being journalistic in that realm as well.

Natalia Antelava: But what puzzles me about you using that pronoun when you were at Google is that the relationship between the media industry and Google was very much a power relationship. And Google had the power that journalism and media didn’t. So why do you use “we” given that there was such a power asymmetry?

Richard Gingras: I mean, I always — I guess we can get hung up on these things, but I always saw it as a collaboration. And I thought it was really important to have it as a collaboration. In fact, let me touch on something. You’ve heard me say this before: You know, we live in an extraordinarily polarized society and time. And we get very simplistic in the way we talk about things. We talk about things in memes, problems in memes and solutions in memes. And it’s not constructive. It doesn’t enable constructive dialogue. And so frankly, when I hear people refer to big tech, or the tech bros, or fake news journalism, or the mainstream media, I go, well, wait a second. In a journalistic context, I find it actually incredibly sad. These are very difficult times and very difficult challenges. And to just make these kinds of simplistic conclusions…

Natalia Antelava: Absolutely. So let’s not talk about big tech and let’s not talk in generalizations. Let’s talk about Google. Google’s relationship with the media was a relationship of power. You had the money, you had the power, you created an ecosystem in which journalism was meant to survive and in which it collapsed. So why “we”? How is that a “we”?

Richard Gingras: I don’t know, I’m kind of lost in the discussion of the pronoun, right? I mean, look, I went to Google 15 years ago. I was at Google actually for a bit before that. I went because I thought in this time of the evolution of the internet — this extraordinary thing called the internet — that being at Google was going to be a very significant place to be in terms of how we expose people to diverse sources of information, in terms of how we might help drive innovation in a time of tremendous change, right? I felt it was important to do that. And frankly, it was the most extraordinary experience of my career. I will tell you, I have never in my career worked with a more significant group of principled, thoughtful people than I did at Google, in Google Search, in Google News, in our relationships with the industry. We were trying to do the right thing. Does that mean we didn’t make mistakes along the way? Of course. Like, you know, search ranking is the mission.

Natalia Antelava: What would you say was the biggest mistake you made at Google?

Richard Gingras: I would say the biggest mistake, honestly, was in our work with the industry, the Google News Initiative. We spent over a billion dollars over eight years, a billion and a half dollars trying to drive innovation.

Natalia Antelava: A tiny line in the budget.

Richard Gingras: Whatever. Who else around the world was spending anything close to that, trying to drive innovation in the news industry?

Natalia Antelava: But that was happening at the same time as Google — along with others, we cannot blame just Google — was also destroying and completely reshaping the ecosystem in which journalism existed.

Richard Gingras: How was that? How was Google destroying that? I’m serious.

Natalia Antelava: Well, because Google was extracting revenue from publishers.

Richard Gingras: No. How? Where?

Natalia Antelava: Was Google not extracting revenue from publishers?

Richard Gingras: Where? How?

Natalia Antelava: The advertising model completely collapsed.

Richard Gingras: Well, let’s go to that point, because again, that’s one of these things that I hear repeatedly. I heard it at a conference in South Africa, [where someone] said “Oh, platforms siphoned newspaper advertising.” You know, that is not factually the case. If you actually — no, look at it: if you look at the makeup — I’ve studied this stuff, carefully.f you look at the makeup of advertising in a newspaper in 1980, 1990, right? 80% of it was four categories: [First] Classified ads, 30%, disappeared into the internet, into online commerce sites. Second, department stores who faded in an era of e-commerce.

Subscribe to our Coda Currents newsletter

Weekly insights from our global newsroom. Our flagship newsletter connects the dots between viral disinformation, systemic inequity, and the abuse of technology and power. We help you see how local crises are shaped by global forces.

Natalia Antelava: And Richard, if I were sitting down with Craig Newmark [founder of Craigslist], I would be asking him different questions, but I would like to ask you questions about Google.

Richard Gingras: And you made a claim, and I think it’s fair for me to respond to the claim, right? Google did not destroy the news industry, did not take their revenue. In fact, another interesting point made by Mr. Siegel last night, which just made me shake my head: “But why did we have to reinvent advertising models?” Two-thirds of Google’s advertisers—not two-thirds of its revenue—two-thirds of its advertisers are small businesses who could not afford to advertise in the world of print. And by the way, as he points out, information is vital to grow an economy. Advertising, particularly in local areas, is valued information to grow a local economy.

Natalia Antelava: So you completely stand by everything that Google did when it comes to journalism.

Richard Gingras: Actually, you didn’t let me answer the question, Natalia. The things that I feel like we didn’t — I don’t think we drove enough innovation. We missed what I see now as a significant opportunity to drive, particularly local news organizations, to rethink what local advertising could be in their communities. I’m chairman of this company, Village Media, which is rethinking what a local media entity can be in this digital world, and it’s entirely supported by local merchant advertising. That was a mistake.

Natalia Antelava: But basically you’re saying that you don’t agree with my premise that the relationship between Google and the media industry was one of power, where Google had all the power.

Richard Gingras: I don’t know how that is even — I’m not even sure how that’s relevant to the conversation. All I knew was, yes, we are, you know, Google Search was a very, very significant component of the—

Natalia Antelava: But that is kind of a yes or no question. Do you think Google — Google News Initiative — in its relationship with the media industry, do you feel like Google had the power?

Richard Gingras: I don’t know. You want me to say ‘yes’? Yes. I don’t understand the point. I mean, do we want to get to the substance of how we move the industry forward?

Natalia Antelava: There are lots of people who would argue that you didn’t move the industry forward — that Google, not you personally, but that Google destroyed the industry. Not just on its own — I know you will argue it wasn’t just Google — but it created the information ecosystem that ultimately advanced the authoritarian rise all around the world.

Richard Gingras: Oh, good Lord. Oh, good Lord. Really? Let’s look at that. No, no, no. Wait a second. Let me answer that because — let’s look at that. One of the things I’ve tried to study and I’ve written about this is the evolution of media and democracy. Let’s see what happened in my country in the United States, right? Let us go back to 1980 when there was deregulation of radio and television. And that was the rise of extreme partisan talk radio, right? Which began to drive our population into very dangerous spaces. And then we had the evolution of cable and cable news networks who went to their partisan cohorts – Fox News. The most significant force in driving division in the United States was that singular company.

Natalia Antelava: I would really like to talk about Google.

Richard Gingras: I understand that, but when you make those kinds of grand statements, I think it’s frankly fair for us to also look at the larger picture.

Natalia Antelava: And you do that, and we do that beautifully and very eloquently in all of your writing, which really focuses on criticizing the journalism industry — which is fair enough, I happen to agree with a lot of what you say about journalism. But it does strike me a little bit like an arsonist who criticizes the fire department for not preventing enough fires.

Richard Gingras: Okay. Let me ask you this: What do you think Google should have done differently?

Natalia Antelava: I think I am the one asking questions here, but let me ask you this: You have written about your father-in-law, Dalton Trumbo — it’s an incredible story. Dalton Trumbo went to prison rather than comply with Congress. And you write about it as a man who really understands authoritarianism, like on a very personal level. It’s very compelling.

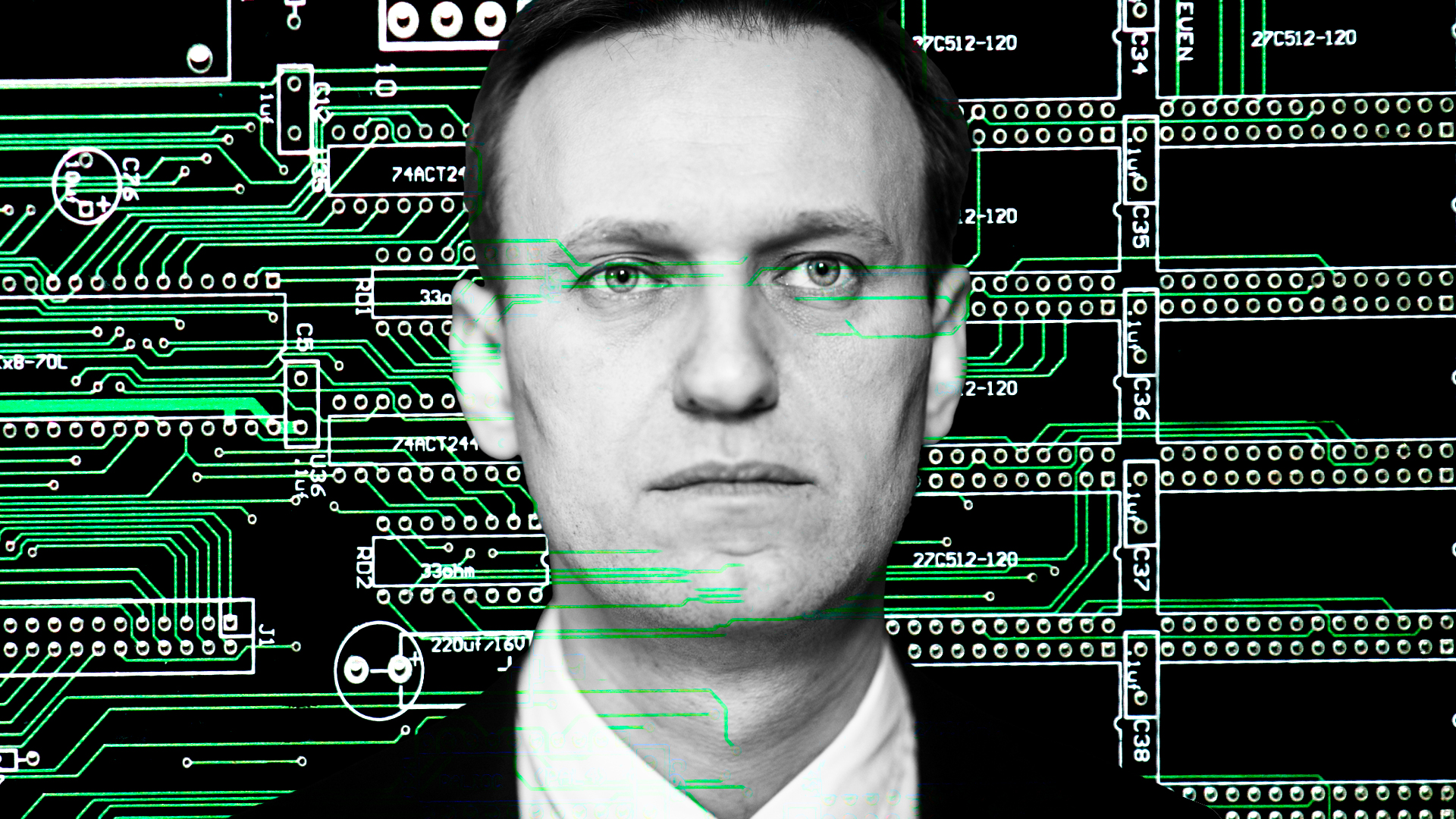

But here’s what it makes me think about: In 2021, during the Russian parliamentary election, Alexei Navalny, who was later subsequently killed in prison, the Russian opposition leader, came up with a very simple and unique way of fighting authoritarianism through elections. It was a voting app. Does anyone remember the name of the voting app?

[Audience member]: Smart Voting.

Natalia Antelava: Smart Voting, it was called the Smart Voting app. And if it had worked — we don’t know whether it would have worked — but if it had worked, then it could have given a lot of people a blueprint for fighting authoritarianism around the world. One of the reasons it didn’t work was because Google complied with the Russian government, with Putin’s demand, to pull the Smart Voting app from Google stores, to pull videos from YouTube, and the whole thing flopped. You were there when these decisions were being made. How did you reconcile your personal beliefs, your family’s story, with the fact that the company you were representing and working for was supporting a very nasty dictatorship?

Richard Gingras: Well, you just made the statement “supporting a nasty dictatorship.” I wasn’t there for that specific decision, so I really can’t speak to it. I can tell you that, for instance, our market share in Russia is tiny, because obviously they have no particular interest in Google Search being successful in Russia. They’ve tolerated YouTube because YouTube is so popular. But we don’t have much of a business there, and they regularly say…

Natalia Antelava: So it had nothing to do with compliance with Putin, it was just…

Richard Gingras: Well, you made the grand statement that we complied and propped up Putin, and frankly, I think that’s nonsense.

Natalia Antelava: What about building censored search engines for China that track dissidents, and continuing business with Saudi Arabia after Jamal Khashoggi died? The Dragonfly [project] allowed the Chinese government to track searches.

Richard Gingras: We didn’t deal with Saudi Arabia… Wait, where did you get this that we built a separate search engine for China? What?

Natalia Antelava: The Dragonfly allowed the Chinese government to track searches.

Richard Gingras: Actually… We pulled out of China because of that. We were not going to go into China with that.

Natalia Antelava: Selling cloud to Saudi Arabia after Khashoggi.

Richard Gingras: You want to just keep talking about that?

Natalia Antelava: Yeah, because this is important context

Richard Gingras: But you make these grand statements without any backup of fact. We were not creating a search engine to go back into China. Full stop.

Natalia Antelava: No, but you can…

Richard Gingras: In fact, if we wanted to go back into China — and I said this at the time — we would have gone into China because we lost a huge amount of business in pulling out of China. We wouldn’t go in with a search engine. We would go in with a simple answer engine that said, “by the way, we’re going to answer questions on all these topics like home renovation and travel and so on. We’re not going to deal with politics at all.” Why would you go back into China and even presume to be a search engine on the open web in China?

Natalia Antelava: So are you saying that Google never complied with authoritarian governments around the world?

Richard Gingras: I’m sure you’ll come up with an example, but I don’t know. You don’t understand the trickiness of the position that we’re in. This is not by the way — yes, we are in, as I’ve said, a company that is like no other company in the history of the world in the middle of so much societal change. And it’s tricky.

Natalia Antelava: Well, the company is the architect of that society.

Richard Gingras: Exactly. I sat down with, for instance, I had an hour-long conversation with the communications minister in a global South country. They wanted to talk about misinformation. I spent an hour talking about that with them and then they came, it was five minutes to go, and the minister said, “Oh by the way, Mr. Gingras, there’s a politician here, and this is a country that doesn’t have great love for the press, that is saying dishonest things about the government. Will you deplatform him?” No, we didn’t deplatform him. We told him what we normally do: “We try to surface diverse sources of information from the press in your country. If that politician is saying dishonest things, then the presumption is that maybe others in the press will challenge that.”

So we’ve tried to be extremely principled in every place we operate. Does that say there have never been issues or challenges of how do we survive in a country and continue forward? Like you’ve made a whole bunch out of the fact that—

Natalia Antelava: So pulling the app in response to Putin’s request to take down the Smart Voting app, that’s principled?

Richard Gingras: We didn’t pull out.

Natalia Antelava: Yeah, you did.

Richard Gingras: Great. Oh, pull the app. You said we pulled out.

Natalia Antelava: You pulled the app, and after that, Google closed the offices.

Richard Gingras: That’s right, because we — that was the principle.

Natalia Antelava: Yes, and I understand that you had the responsibility for your staff in the country. That is also understandable. But pulling the app — you just said Google was always principled, but that is not principled. And look, I’m not holding you responsible for the decision at that level, but I’m asking you for your reflections on how that squares with your beliefs and things that you talk about, about authoritarianism, about freedom. That’s what I’m trying to get, I am trying to get your reflection on it.

Richard Gingras: My reflection, in general, because the issues you specifically raised are issues that I was not involved in. It wasn’t my job. At those times, I was a VP of product in Search, also overseeing things like news and so on and so forth. So where was I? These are extraordinarily difficult times and difficult circumstances. I generally believe that Google tried, and Sundar Pichai is an incredibly principled fellow. We try to do as best we can in these complex times, in this complex world. Thank you very much.

Natalia Antelava: But, do you agree that it’s not a principled thing to do, to pull the app?

Richard Gingras: There’s many things that we can look at and say that was not necessarily the right decision. I didn’t say we were flawless at all. We try to learn as best we can from every mistake we make and go forward. That’s what we did at Google. Now, it’s not “we” anymore because I’m not there, but I do have tremendous respect for the people there, including Sundar for that matter. And there’s, you know, all kinds of nonsense has been made out of that photo at the inauguration. We’ve been at every inauguration for the last 20 years. And yes, the White House was very clever in staging that situation such that that photo happened. And I know full well that that’s the last photo Sundar ever wanted taken. We don’t support this administration.

Natalia Antelava: Richard, I have another question. Let’s talk about something else. So you just published a piece that you sent me about what you call the Woodward-Bernstein effect, talking about Watergate and how it’s kind of set the precedent for journalism being really obsessed with accountability reporting at the expense of other kinds of journalism. It’s an interesting argument and there is a lot that I agree with. What bothers me about that piece when I read it is that it’s coming from you, because for so long while you were at Google, Google was one of the most opaque, non-transparent and difficult organizations that I have ever dealt with as a reporter. It was impossible to get an answer from Google on anything that Google did. How do you square that?

Richard Gingras: What? I don’t know how to square your experience at all. I know that when it comes to Google Search, I spent so much of my time—and the reason I say these things, by the way, I do consider myself a journalist. I consider myself having been in this space for five decades. And so I will stand on that in terms of the opinions I make about how journalism might move forward.

Natalia Antelava: Yeah, and you have great opinions, but what puzzles me is why are we not hearing your reflections about Google, your employer, for 15 years? You criticize journalism a lot and a lot of this critique is incredibly prescient, but what about reflections on…

Richard Gingras: I’d gladly reflect, but what you’ve asked me to reflect on is things that I wasn’t involved with. So, you know.

Natalia Antelava: Yes, but you reflect on things in journalism that you were not involved in.

Richard Gingras: Let me try it. Once again, Natalia, if I have an opportunity to answer the question, I’ll do it more broadly, OK? If I think there’s something that we never did enough of, particularly with regard to our algorithmic work — and I’m extremely proud of our algorithmic work — and one of the things we always did with Google Search, particularly, said, “Well, we show the results every day. We will encourage research of people looking and analyzing our research and giving us that feedback.” I think a mistake we made was we never spent enough time explaining how we did our work. We assumed people would understand. And they don’t. I spent so much time in the last 10 or 15 years on the policy space and every time I would meet with a minister in another country, you were starting from scratch because they had no clue how Google worked. They didn’t understand the business, they didn’t understand how search worked.

Natalia Antelava: What did Google not understand? But is there something that Google didn’t understand? I’m trying to get you to answer that.

Richard Gingras: I’ll tell you what Google — here’s one of the things that Google didn’t understand, is we don’t understand the public policy environment. You know why? Because we’re a bunch of engineers. We’re a bunch of logicians. I remember when I first met — when Axel Springer moved forward with Leistungsschutzrecht [the German ancillary copyright law], right, another bad example of public policy, pay for links, right? And I explained this, so I had to go brief Larry [Page] about this. And as typical with Larry, he was very smart. And he said, well, that’s just fucking stupid. And he’s right. It was stupid. It made no sense for the industry.

Natalia Antelava: Yes, it didn’t make sense for the profit part.

Richard Gingras: Can I finish my answer, Natalia? The reason it didn’t make sense for him was that he’s a logician. And I said: “But Larry, here’s the thing. In the public policy environment, logic doesn’t even get invited into the room. It’s a battle of particular interests. And if we want to be effective in that environment, then we have to do a whole lot more outreach. We have to do a whole lot more talking. We have to do a lot representing what we do and why we do it.” All right, there’s a reflection.

Natalia Antelava: But, isn’t what you do and why you did it — profit? The bottom line was always profit.

Richard Gingras: Are you saying there’s something wrong with…

Natalia Antelava: No, not at all. I’m not saying there is something wrong….

Richard Gingras: I do find it interesting here that we like to toss around the word non-profit as if it were a cloak of ethics. It’s not a business model, it’s a tax status. What we all need to be much more focused on is how do we drive sustainable news businesses. And yeah, Google—

Natalia Antelava: Yeah, but that’s exactly the point I’m making. What Google was always focused on was not driving sustainable news businesses. It was focused on driving its own business, which did not go hand-in-hand with sustainable journalism.

Richard Gingras: And again, if you want to be specific, in what ways you thought that was contrary to our societal interests, I’d like to hear it. I mean, look at it.

Natalia Antelava: Oh, does it?

Richard Gingras: Fine, say it, hear it. Can we be specific?

Natalia Antelava: I just gave you a bunch of examples from Russia, Saudi Arabia. There are others: Vietnam, Turkey…

Richard Gingras: OK. We try to survive in those countries as best we can without pulling out because we don’t think it’s in the best interest — like in the United States we got a government that could destroy us in a heartbeat. We’re trying damn hard not to be destroyed because we don’t think that’s A) good for our business or good for the societies we operate in. And we will try to continue.

Natalia Antelava: Yeah, it’s “we,” you are still saying it. I find it interesting that you say “we” both about the news industry as well as Google and I think these are two very different “we’s” because these are two entities that hold completely different power in today’s information ecosystem, in which the noise is overwhelming and journalism cannot get through the noise. Part of that is the architecture of the way modern information works, and Google played a key role in being the architect.

Richard Gingras: No, listen, architect of what?

Natalia Antelava: Of the current information ecosystem.

Richard Gingras: What? Operating Google Search? Operating auction-based advertising systems? Tell me what? No, go ahead, tell me what.

Natalia Antelava (addressing voices from the room): Would anyone like to say something?

Richard Gingras: Auction-based advertising systems have created great efficiencies in the economy. Go ahead.

[Audience member]: Sure, so we know that the Department of Justice has found two illegal monopolies, so it’s not an opinion, it’s a legal finding that Google had monopoly rents on search. So Google was found to have an illegal monopoly in search, that included in terms of advertising search and search visibility, and it was found to be an illegal monopoly in [ad tech]. And what does that mean? That means that it took monopoly rents. That was preferential dominance. And so that doesn’t have anything to do with—that was how you siphoned off revenue. So this is not an opinion of Natalia’s. This is what has been determined by a US court and then many competition authorities around the world that have done investigations to look at Google’s market power, as you said, in all of these domains, including now building the next generation of AI, the whole AI ecosystem, redoing the information ecosystem, and revising copyright, which has been around for hundreds of years, to self-preferencing, forcing us to use those tools in Google products without any choice. No consent, no compensation, no credit. Google search would not be very useful if it didn’t have fact-based information, just as AI is not useful without fact-based information. But there is not a fair exchange of value. There is no payment for copyright. There is no payment for the use of raw data, which creates the—

Richard Gingras: And by the way, we didn’t revise copyright, we are operating within copyright today. Google is operating within copyright today.

[Audience member]: No, I mean, there are so many publishers that have aligned to create, to try to get their rights, their copyrights. But Google has so much money that it can afford to resist more than 54 lawsuits that are happening around the world.

Richard Gingras: Again, right, let the courts decide.

[Audience member]: They have decided…

Richard Gingras: You want me to give constructive [advice] to the industry, as me, not as Google, talking about AI? Go ahead, put up the robots.txt. Feel free. Pay to crawl {a bot that browses the net and discovers raw data from webpages, a critical step for search engines to function].. Great. My only guidance to you would be: be very cautious about what you expect in return dollar-wise. And if you want to analyze the information economy at large, you’ll get a pretty clear understanding of where the value is and where the value isn’t, right? But do that. I have no problem with that personally at all.

[Audience member]: We did it. [Another publisher] did it, I did it!

Richard Gingras: Great, do it, and then fine, and you can block whoever you block. That’s fine, go ahead, but that’s not a copyright issue. If there are copyright lawsuits and lawsuits that win, fine, but I haven’t seen them yet.

[Audience member]: The Thompson Reuters case.

Richard Gingras: And just think, wait, let’s see how the courts resolve those issues. But again, the same point is, if you want to block the crawlers, block the crawlers. If you want to try to extract payment from the crawler, extract payment for the crawlers, so be it. I don’t disagree with that.

Natalia Antelava: I mean the issue with that is that if you control the oxygen and then you tell people “you don’t have to breathe this air if you don’t want to”—

Richard Gingras: What do you mean control the oxygen?

Natalia Antelava: I think everyone in this room understand the metaphor. Can you raise your hand if you know what I mean?

(hands go up)

Richard Gingras: Well don’t, why don’t you just explain it to me instead of talking in metaphors?

Natalia Antelava: Richard, I think of all people you really understand metaphors.

Richard Gingras: Thank you. Okay, Natalia, I don’t know what to say. When you say you control the oxygen, what does that mean? Seriously, you giggle, just answer the question. Is it that hard to answer?

Natalia Antelava: You control the ecosystem in which publishers had to survive.

Richard Gingras: What control? Google Search? Control? Look, here too. Really interesting. When they say gatekeepers, we came from a pre-internet ecosystem where breaking into the dialog of the media was extraordinarily difficult. Now we have this thing called the internet and we have these things called search engines which help you find these sources. Now if you want to criticize the algorithm, criticize the algorithm and I’ll gladly defend that or not. And if you want to be specific about those criticisms, do…

Natalia Antelava: No, I’m much more interested in—

Richard Gingras: But if you want to be in search, then yes, we need to crawl

Natalia Antelava: Yeah, that’s right. That’s what I mean. You control the oxygen and say “go ahead and breathe some other air”

Richard Gingras: What are you suggesting as the alternative model? I want you to just kind of play some of these scenarios through for a second. Because I’m saying, we need to pass a law saying that LLMs need to pay for the content they crawl. Can I finish the point, Natalia? Think of how that might play out. Because I suspect what might play out is those LLMs—first of all, the money isn’t in news at all. It’s not in news at all, it’s not what the enterprises are paying for, so there’s not gonna be a whole lot of money to be spent—but what they will do is they’ll go pick off a number of publishers or wire services here, a big publisher there, and it’ll be end of story. So much for that nice, wonderful, diverse ecosystem that we’re talking about here. It won’t happen. So again, you can impose that model. Is that ultimately to the benefit of the knowledge ecosystem of the world? I kind of question that.

Natalia Antelava: I mean, the knowledge ecosystem that is very questionable and is full of rubbish — I’m not blaming you for that. What I’m trying to get out of you are genuine reflections about the specifics. You’re very good at giving them when it comes to critique of the media and you’re not able to do it at all when it comes to critique of the company that was your employer for a long time. It sounds like you did everything right and publishers did everything wrong.

Richard Gingras: I did not say that, I did not say that Natalia, you know, honestly, you put words in my mouth, you raise non-specific questions for me to react to.

Natalia Antelava: I think I raised very specific questions.

Richard Gingras: These are specific questions about things that I again [was not a part of], I worked in search.

Natalia Antelava: But you understand how the power structures work. And you using the “we” pronoun and hosting journalists and being part of the journalism industry conversation has helped Google to obscure the fact that it was also destroying the business.

Richard Gingras: Again, people can decide whether they want to engage with Google or not.

They don’t have to come to conferences that we’ve sponsored, they don’t have to use the tools that we have provided, you don’t have to at all.

Natalia Antelava: Because if you don’t, you don’t exist. But since you brought up conferences, there is one question I’ve always wanted to ask you. I’ve only been to one News Geist — two News Geists [Google’s annual conference for publishers] — as probably most of you in the room know. I went to Athens, was never invited back, I wonder why… But the one memory that I have from News Geist — it was a great conference, excellent conversations, really fun dinners, fantastic cocktails at the bar — and you know, one night after the cocktails, after everyone had lots of cocktails, all these people gathered into the ballroom for the big News Geist tradition, the Werewolf game. And those of you who don’t know, it’s basically like the same kind of game as Mafia. It’s a power and deception game, where you’ve got the killers and the innocents – the villagers and the werewolves. And then you have the game masters. And this is happening at a time when lots of publishers are shutting down and the business is in tatters and, you know, there’s this Google-facilitated conversation about how we can save journalism. And here I look across this room and there are several big circles of chairs and on the chairs are senior editors and publishers from across Europe and many of them are blindfolded or they’ve got their eyes closed and Google executives, yourself included, were going around playing the game masters, commanding when people could see, when they couldn’t see, who lives, who dies. Did it ever cross your mind that this was a metaphor for Google’s relationship with the media?

Richard Gingras: Good lord. Okay, so let me give you a quick bit of history. Our conferences came out of the software industry. They were called FooCamps. O’Reilly Publishing decided to do one for news called News Foo. And then they decided, well, not a very good business, and so Google said we would do it. Now it’s like 12 years ago. And we’ve done these around the world. It’s an absolutely great model. I wish more people would use it. Werewolf was part of it way before we started it. We didn’t pick the game. It’s a fascinating game. Reporters particularly like it because it’s an interesting game that gets down to, can I detect when someone is lying or not? It’s a game.

Natalia Antelava: Did it ever, after years of doing News Geist, did it ever cross your mind that this is a metaphor for Google’s relationship with the media? Because I’ll tell you, this is what everyone else thought!

Richard Gingras: No, it didn’t. Oh gosh. Oh my gosh. No, no. So let me just say one thing.

Natalia Antelava: We are out of time.

Richard Gingras: Let me say two things. First of all, I’m here representing my own views. I’m also here representing an organization called CNTI [Center for News, Technology & Innovation], which was founded by the likes of Marty [Baron], Paula [Miraglia], me, Maria Ressa. That organization was founded to foment dialogue on these complex issues between different people. We don’t always agree on things. So I want to be clear. What I’m speaking here for is my views. And by the way, our conference is going forward, News Geist is going forward. It’s run by CNTI. What a nice thing. We’ve moved it from Google to CNTI. We hope to be doing one in Europe.

Natalia Antelava: Google’s still paying for it, though.

Richard Gingras: Google’s a sponsor. So if you want to come up with $150,000 to sponsor the event, we’ll gladly take your check. But Google has never imposed their agenda on it. We don’t even have logos up at the event.

Natalia Antelava: That is really the power of Google, when you don’t need logos.

Alright, thank you so much. I really hope that we will all get to read pieces by you about your time at Google that have the same analysis and depth as your critiques of journalism.

Postscript: Gingras sat for this interview knowing the questions would be uncomfortable, which deserves acknowledgment. At the end, he said I should have been more specific in my questions. I would welcome the opportunity to continue this conversation with whatever specificity he’d like. His current writing on journalism and media can be found here.