The current wave of unrest is the most serious internal challenge to the Islamic Republic since it emerged after the overthrow of the monarchy in 1979.

But does it mean the regime is at its last gasp? Or will these events be added to a long list of inconclusive revolts that started well before the “Green Revolution” that followed the 2009 election, through to the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement in 2022?

The latest signs are that the protests may be waning. But there are at least three new elements that make this latest uprising different and which may rise again later even if the regime survives.

The protests were kicked off by the Bazaar in Tehran, the conservative mercantile class, normally the last to want to rock the boat. Like a bushfire, it spread with lightning speed to towns and cities across the country, fuelled by grievances that had surfaced in previous protests. So, the initial impulse came from the country’s disastrous economic situation. With the national currency, the Rial, losing 84% of its value over the past year alone, inflation had brought crushing hardship to many despite the regime’s efforts to apply bandaids to the gaping wounds. The involvement of the Bazaar gave the protests a new depth. The second novel element was the sudden emergence, around ten days into the uprising, of Reza Pahlavi, son of the ousted Shah, as a figurehead for the protests. “Javid Shah, Long live the Shah!” became one of the main battle cries of the protesters. The dissident movement lacked unity, leadership and a shared platform. The hope was that Reza Pahlavi could act as a unifying figure who might oversee a transition to a democratic future.

Adopting him may have been a sign of desperation, but it was also a red rag to the regime, a provocation impossible to ignore. A third new feature was the unprecedented level of outside interference, whose direction and intentions were far from clear at the outset. Fresh from abducting Nicolás Maduro and vowing to “run” Venezuela, Donald Trump seemed in the mood for further adventures, urging Iranian “patriots” to keep protesting, and telling them that help was on the way. Much would clearly depend on what form that “help” would take. But by tying it so clearly to Iran’s internal situation rather than the nuclear or missile issues that underlay the 12-day Israeli-U.S. war on Iran in June last year, Trump’s intervention was giving the uprising a dimension it lacked before.

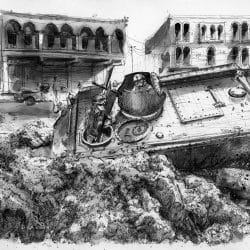

All this amounted to what the regime clearly saw as a potentially mortal threat, and it reacted with unprecedented ferocity. Though the full picture has yet to emerge because of the communications blackout, there are horror stories of overflowing morgues, many gunshot wounds to eyes and genitals, machine guns mowing down crowds, and many other brutalities that seemed to succeed in tamping down the flames. Opposition human rights groups believe the death toll is closer to 12,000 than the 2,000 initially announced by the regime, which was already a good deal higher than for previous uprisings.

Left in a purely Iranian context without the U.S. wild card, the regime, although rattled, seems to have survived another round of challenge, though with consequences that may surface later. As Israeli military analysts had pointed out, the Iranian authorities had many repressive tools they had not yet deployed. There was no sign of a crack in the loyalty of the security forces or of serious splits within the government. Bear in mind that the Revolutionary Guards (the IRGC), in addition to their powerful military machine and auxiliaries (the Basij), also wield huge economic clout on which hundreds of thousands of families depend.

If this round has been crushed internally, there will surely be another round later unless there is a radical change. The decision by activists to adopt Reza Pahlavi did not reflect a widespread longing for the monarchy; it was rather a signal that the opposition had given up hope of changing the regime from within, and that overthrow was the only way forward, with Pahlavi as the only visible symbol of defiance to rally around. But even Donald Trump cast doubt on the level of support inside Iran for the aspiring “Crown Prince.”

The regime’s only hope of treating the dire economic crisis swiftly and undercutting protest would be to bring about a lifting of ever-tightening sanctions, which means coming to terms with the Americans. And that raises the question of U.S. (or Trump’s) intentions. In the 12-day war last June, Israel clearly wanted to continue a campaign of detailed bombing that could have led to regime collapse, while Trump was content with one spectacular strike. His instinct is not to get embroiled in lengthy open-ended hostilities.

Regime change in Iran would very likely produce chaos, and perhaps fragmentation of the country as a unitary state. It is very hard to imagine a smooth transition to democracy, and very easy to see Kurdish, Arab, Azeri Turkish, Sunni Baluchi, and other minorities splintering away as vying factions struggle for power in Tehran. That may suit Israel’s playbook for regional disintegration, but the transactional Trump likes to do deals with unified states; witness Syria, where Israel favours a weak, decentralized state, but the U.S. wants a unified, cooperative one under al-Sharaa; and Venezuela, where Trump has left the regime in place and spurned the opposition despite removing Maduro.

If it remains committed to some form of action against Iran, the U.S, would have to calibrate its moves with great care. Striking nuclear or missile facilities again would likely have little effect on the regime, but would provoke a reaction against U.S. bases in the Gulf that might not be as cosmetic and choreographed as it was last June. American strikes against political, military or security targets would have to be sustained and detailed or would end up being ineffective or counter-productive, and if effective, could produce collapse and chaos. Might Trump dream of doing a Maduro on the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamene’i, leaving the IRGC and others to do a deal? Anything is possible. But in Iran, nothing is simple.

While Israel was standing by watchfully and hoping for a tough U.S. response, there were countervailing pressures from America’s Gulf Arab allies, deeply unsettled by the crisis. They don’t want to be hit by an angry Iranian neighbor, while the possibility of regime collapse and fragmentation opens up all kinds of prospects of regional instability and danger. The signs are that these representations have hit home with Trump.

But Iran remains a mess with no easy resolution. And it’s not going to go away.

A version of this story was published in this week’s Coda Currents newsletter. Sign up here.